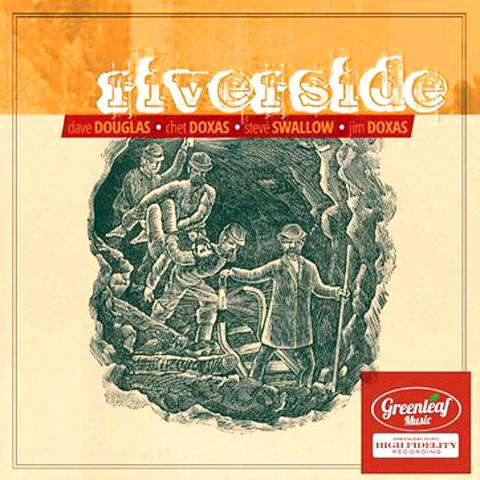

Riverside

Riverside

Greenleaf

One of the lovelier songs on Riverside, the self-titled debut album of a sturdily approachable new jazz quartet, bears the title Old Church, New Paint. A slow waltz by the tenor saxophonist and clarinetist Chet Doxas, from Montreal, it inhabits a kind of arid terrain between Protestant hymn and cowboy tune.

The industrious trumpeter Dave Douglas, who actually made a recent album of hymns, joins Doxas on the melody, helping give the impression of deliberative but bluesy determination. Steve Swallow, the electric bassist, lays both a foundation and a light dusting of grace notes, while Jim Doxas, a drummer (and Chet’s brother) stirs the pulse with brushes. The band, which will appear at the Jazz Standard on Tuesday and Wednesday, sounds at ease with itself, and anything but hurried.

Riverside grew out of a shared respect for the Texas-born multireedist Jimmy Giuffre, who during the 1950s and ‘60s cut a path from swing and West Coast bop toward an early, untroubled strain of free jazz. Douglas and Chet Doxas, on learning that they both loved Giuffre’s music, conceived of a setting for new work in the same spirit, reaching out to Swallow, who played in an influential edition of the Jimmy Giuffre 3.

The album includes one Giuffre tune, The Train and the River, which semi-famously graced television (The Sound of Jazz, on CBS) and film (Jazz on a Summer’s Day, Bert Stern’s documentary about the 1958 Newport Jazz Festival). Elsewhere, the album sees fit merely to evoke Giuffre’s airy, wide-open harmonic sensibility and a loose frame of jazz-historical reference. (Old Church, New Paint suggests a nod to the Gil Evans album New Bottle Old Wine, which came from the same cohort and time period.)

Chet Doxas, who has never had a high profile in this country even by a jazz metric, hits his every mark, with a soulful and rhythmically assertive style on tenor saxophone and a warm, woodsy tone on clarinet. Douglas, who wrote most of the tunes, is even more squarely in his element, though there’s a fresh tang in his rapport with Swallow, whose rubbery, insinuative bass lines are the key to the album’s deeper charms. However the homage to Giuffre plays out, this is a band that could easily keep going for a while without running out of options.

— By Nate Chinen, NY Times News Service

Make My Head Sing ...

Jessica Lea Mayfield

ATO

Jessica Lea Mayfield makes a brash sonic swerve on Make My Head Sing ..., her third album. Her first two, both produced by Dan Auerbach of the Black Keys, leaned toward the raw, depressive edge of roots-rock, with mostly quiet songs that occasionally lashed out. Mayfield — who was 19 when her stark, eerie debut album, With Blasphemy So Heartfelt, was released in 2008 — started performing as a child in her family’s bluegrass band, and while neither of her first two albums strove for any kind of traditionalism, her country and folk underpinnings were clear.

Make My Head Sing ... blasts those qualities away from the first notes of its opening song, Oblivious: loud, slow, unaccompanied, heavily distorted guitar chords, soon joined by an equally slow and deliberate drumbeat. It’s closer to the proto-grunge of the Melvins than to any kind of Americana, and the transformation of the lyrics is equally brash: “I could kill with the power in my mind,” Mayfield sings.

Mayfield played guitars and produced the album with her bassist and husband, Jesse Newport, backed by a drummer, Matt Martin. With Mayfield often playing baritone guitar, lowering the pitch of the central guitar chords, they put a feedback-edged grunge power trio at the core of the songs: the sound of trouble, obsession, foreboding, decadence. But Mayfield doesn’t rasp like a flannel-shirted rocker; her voice stays clear and oddly calm as she sings lines like, “When it’s just us two in the dark/You’ve got a stranglehold on my heart.”

As a whole, the album is monochromatic, too single-minded about Mayfield’s new sound — and, at times, a little too determined to reverse-engineer Nirvana’s flanged guitar effects. And her laconic new lyrics don’t always offer the subtleties and paradoxes of her earlier songs.

But individual tracks are telling. Among them are I Wanna Love You, which is more about stalking than romance; Do I Have the Time, which charges into a polymorphous wilderness of desire and infidelity; Party Drugs, a hollow-eyed ballad set to a lone guitar in which the singer reassures someone, “I won’t die in this hotel room”; and Anything You Want, with a heaving riff and a girlish-voiced, matter-of-factly foreboding refrain: “You get away with anything you want.”

Make My Head Sing ... probably doesn’t stake a permanent new direction for Mayfield. It signals, instead, that from now on she’ll do whatever she wants.

— By Jon Pareles, NY Times News Service

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

When the South Vietnamese capital of Saigon fell to the North Vietnamese forces 50 years ago this week, it prompted a mass exodus of some 2 million people — hundreds of thousands fleeing perilously on small boats across open water to escape the communist regime. Many ultimately settled in Southern California’s Orange County in an area now known as “Little Saigon,” not far from Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton, where the first refugees were airlifted upon reaching the US. The diaspora now also has significant populations in Virginia, Texas and Washington state, as well as in countries including France and Australia.

On April 17, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) launched a bold campaign to revive and revitalize the KMT base by calling for an impromptu rally at the Taipei prosecutor’s offices to protest recent arrests of KMT recall campaigners over allegations of forgery and fraud involving signatures of dead voters. The protest had no time to apply for permits and was illegal, but that played into the sense of opposition grievance at alleged weaponization of the judiciary by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) to “annihilate” the opposition parties. Blamed for faltering recall campaigns and faced with a KMT chair

A police station in the historic sailors’ quarter of the Belgian port of Antwerp is surrounded by sex workers’ neon-lit red-light windows. The station in the Villa Tinto complex is a symbol of the push to make sex work safer in Belgium, which boasts some of Europe’s most liberal laws — although there are still widespread abuses and exploitation. Since December, Belgium’s sex workers can access legal protections and labor rights, such as paid leave, like any other profession. They welcome the changes. “I’m not a victim, I chose to work here and I like what I’m doing,” said Kiana, 32, as she