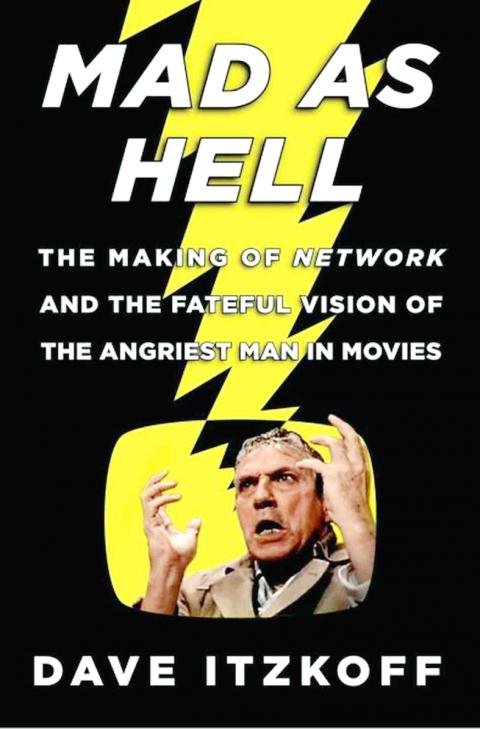

In the closing chapter of Mad as Hell — informatively subtitled The Making of ‘Network’ and the Fateful Vision of the Angriest Man in Movies — Dave Itzkoff lays out how the American media has become even more Chayefskyian in the decades since Paddy Chayefsky, the angry man in question, wrote his crazed, perceptive, unwieldy, galvanizing satiric fantasia set in the world of network television news.

Yet Itzkoff, a culture reporter for the New York Times, doesn’t go far enough. How could he? Between the time the covers were glued on his lively and terrifically detailed account and this very minute, the media world has become more Chayefskyian still.

Rachel Maddow, a real-life, crusading left-wing journalist, now appears as Rachel Maddow in an episode of the snake-pit Netflix drama House of Cards, about a scheming, fictional politician. Giant cable company Comcast plans to acquire giant Time Warner Cable to create an earth-stomping commercial behemoth. Jeff Zucker, president of CNN Worldwide, announces that he wants more reality programming, more of “an attitude and a take,” “more shows and less newscasts” on the Cable News Network.

These times confirm the pinwheeling visions of Howard Beale, the anchorman and “mad prophet of the airwaves” in Network. If, when the movie was first released, the words Chayefsky put into Beale’s mouth were considered outrageous, today they sound eminently sane.

“Right now,” proclaims Peter Finch as Beale, “there is a whole, an entire generation that never knew anything that didn’t come out of this tube. This tube is the gospel, the ultimate revelation; this tube can make or break presidents, popes, prime ministers; this tube is the most awesome goddamn force in the whole godless world, and woe is us if it ever falls into the hands of the wrong people!”

“Right now” was when Chayefsky won the 1976 screenwriting Oscar for his howl against cutthroat network executives and sheeplike viewers, cynical programmers and dumbed-down pop culture, the dual American malaise of infectious personal apathy and metastasizing corporate greed. Not that his howl was universally well received at the time. Itzkoff’s narrative is thorough yet brisk as he catalogs the good and the bad that befell Chayefsky and his passion project. It is fortified with vivid anecdotes pulled from generous access to the Paddy Chayefsky papers at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts and to the Network script supervisor Kay Chapin’s observant production diary. Among the many interviews conducted, those with the screenwriter’s son, Dan Chayefsky; his longtime producer, Howard Gottfried; and the Network cinematographer, Owen Roizman, are particularly illuminating.

The movie stung industry insiders. “Awful,” “just such a caricature,” “simply couldn’t happen,” said Richard S. Salant, then president of CBS News. It also divided critics. “Brilliantly, cruelly funny,” Vincent Canby said in the New York Times; “a mess of a movie,” said Frank Rich, then a movie critic at the New York Post.

Still, it was nominated for 10 Academy Awards, and won four, including Chayefsky’s for screenwriting. Faye Dunaway won best actress for her performance, both chilling and sizzling, as a ruthless programming executive; Beatrice Straight won best supporting actress for her small but piercing role as an executive’s wronged wife; and the best actor award went, posthumously, to Finch, who died of a heart attack in January 1977. (The director, Sidney Lumet, lost to John G. Avildsen, who directed Rocky.)

But what of it? “Los Angeles did not really suit his temperament,” Itzkoff says of Chayefsky; “neither did awards ceremonies, nor did fawning attention.”

Some of that prickliness was in self-respecting service to his talent, which Chayefsky was justly proud of; he had rare and absolute creative control over his scripts, and brooked no changes in his famously wordy monologues. (Finch could make it through the mad-as-hell speech in its entirety only once, and Lumet shot only two takes; the final version uses a portion of each.) Some of that was blunt cantankerousness, and, as Itzkoff puts it, Chayefsky’s “familiar, cynical form.” Some of it was no doubt a carapace to protect an artist’s thin skin. He died of cancer in 1981, at the age of 58.

Mad as Hell is most engrossing when the focus is on how the work actually got done: how the screenwriter wrote and cut and rewrote; how the director shot and planned the next shot; how the casting was completed; and how the producer, director and screenwriter accommodated their fancy constellation of stars. (An account of the negotiations necessary to produce Dunaway’s great sex scene with William Holden is irresistible.) And if the emphasis on Chayefsky’s Chayefskyness occasionally wears thin — yes, yes, we get it, he’s mad as hell! — there is more than enough prescient wisdom tossed off in his notes and drafts and dialogue to absorb the reader.

“The thing about television right now is that it is an indestructible and terrifying giant that is stronger than the government,” Chayefsky jotted down. “It is possible through television to take a small matter and blow it up to monumental proportions.” That was just a note in an early draft. Preach it!

The canonical shot of an East Asian city is a night skyline studded with towering apartment and office buildings, bright with neon and plastic signage, a landscape of energy and modernity. Another classic image is the same city seen from above, in which identical apartment towers march across the city, spilling out over nearby geography, like stylized soldiers colonizing new territory in a board game. Densely populated dynamic conurbations of money, technological innovation and convenience, it is hard to see the cities of East Asia as what they truly are: necropolises. Why is this? The East Asian development model, with

June 16 to June 22 The following flyer appeared on the streets of Hsinchu on June 12, 1895: “Taipei has already fallen to the Japanese barbarians, who have brought great misery to our land and people. We heard that the Japanese occupiers will tax our gardens, our houses, our bodies, and even our chickens, dogs, cows and pigs. They wear their hair wild, carve their teeth, tattoo their foreheads, wear strange clothes and speak a strange language. How can we be ruled by such people?” Posted by civilian militia leader Wu Tang-hsing (吳湯興), it was a call to arms to retake

This is a deeply unsettling period in Taiwan. Uncertainties are everywhere while everyone waits for a small army of other shoes to drop on nearly every front. During challenging times, interesting political changes can happen, yet all three major political parties are beset with scandals, strife and self-inflicted wounds. As the ruling party, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is held accountable for not only the challenges to the party, but also the nation. Taiwan is geopolitically and economically under threat. Domestically, the administration is under siege by the opposition-controlled legislature and growing discontent with what opponents characterize as arrogant, autocratic

When Lisa, 20, laces into her ultra-high heels for her shift at a strip club in Ukraine’s Kharkiv, she knows that aside from dancing, she will have to comfort traumatized soldiers. Since Russia’s 2022 invasion, exhausted troops are the main clientele of the Flash Dancers club in the center of the northeastern city, just 20 kilometers from Russian forces. For some customers, it provides an “escape” from the war, said Valerya Zavatska — a 25-year-old law graduate who runs the club with her mother, an ex-dancer. But many are not there just for the show. They “want to talk about what hurts,” she