There is something immediately warm and charming about Mon Marche. It’s a cafe run by a young couple, whose artistic flair is evident in the way they’ve transformed an old two-story apartment building into a restful haven that serves light meals, handmade desserts and pastries.

Located in a quiet lane near the bustling intersection of Xinyi and Anhe Roads, the cafe greets patrons with a laid-back atmosphere spiced up with lively decor in olive green, Turkish blues and mustard yellow.

In random corners, playful paintings lean against the wooden brown backdrop, while floral prints decorate parts of the wall to exude a tang of femininity.

Photo: Ho Yi, Taipei Times

The most amusing work of design in the house is a small opening on the second floor, which allows an unobstructed view of the open kitchen on the ground floor from above and makes the place seem more spacious than it actually is.

As pleasant and mellow as the establishment itself, the young proprietors are instantly likable with their genuine smiles and amiable service. On the day my dining companions and I visited, the hostess was particularly helpful in recommending items from the small but solid selection of craft beer and red and white wine. For those seeking non-alcoholic refreshments, Mon Marche offers choices of organic and fair-trade coffee (NT$120 to NT$190) as well as an assortment of Mariage Freres teas (NT$170 and NT$180).

The popular curry rice with pork (炙燒豬肉咖哩飯, NT$240) might appear mild and agreeable — it comes prettily arranged with cherry tomato, a sunny-side-up egg and lettuce — but is in reality a fierce little dish packed with punch. Equally good is the chicken meatball and rice (燉雞肉丸飯, NT$280),which presents the tenderly cooked, juicy meatball half-immersed in a spicy sauce.

Photo: Ho Yi, Taipei Times

Evidently, the kitchen of Mon Marche is prone to improvisation. One of my friends was told that the fried beef with pesto (青醬爆翼板牛飯, NT$350) he ordered was not available. He happily found that its replacement — the duck breast with cream sauce (白醬鴨胸飯, NT$350), which was not listed on the menu — was satisfyingly composed of thin slices of meat that were properly fatty.

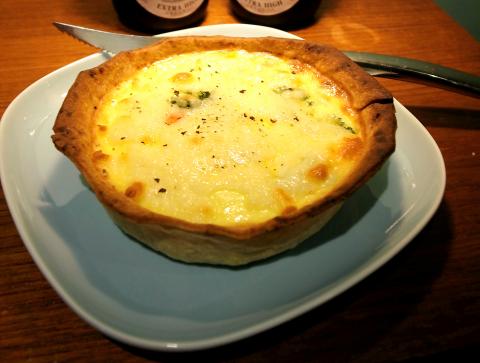

The high point of our dinner came in the form of the mushroom quiche (NT$250 for a set that comes with salad plus tea or coffee). The pie is said to be freshly made in the kitchen on a daily basis, and the freshness shows. The quiche was so good that I had to order one more to go, and that one was equally delicious eaten cold the next day. The quiche comes in two other flavors: salsa and pesto chicken.

For a lighter meal, diners have three choices of sandwich, including smoked ham with cheddar cheese (切達里肌三明治) and orange-flavored curry chicken (橙香乳酪咖哩雞三明治), which also costs NT$250 as a set meal with salad and drinks.

Photo: Ho Yi, Taipei Times

A visit to Mon Marche is not complete without the desserts and pastries handmade by the hostess, who had traveled to Paris to learn from the Parisian patissiers. One of her signature items is tartin (NT$150), an upside-down apple tart that’s made by caramelizing fruit in butter and sugar amd then adding a pastry top. The clafoutis (NT$220) is a baked fruity dessert consisting of berries and apples. Served lukewarm, the dessert is a great choice on wintry days.

A word of reminder: Mon Marche is a popular restaurant and reservations are a must.

Photo: Ho Yi, Taipei Times

Photo: Ho Yi, Taipei Times

June 2 to June 8 Taiwan’s woodcutters believe that if they see even one speck of red in their cooked rice, no matter how small, an accident is going to happen. Peng Chin-tian (彭錦田) swears that this has proven to be true at every stop during his decades-long career in the logging industry. Along with mining, timber harvesting was once considered the most dangerous profession in Taiwan. Not only were mishaps common during all stages of processing, it was difficult to transport the injured to get medical treatment. Many died during the arduous journey. Peng recounts some of his accidents in

A short walk beneath the dense Amazon canopy, the forest abruptly opens up. Fallen logs are rotting, the trees grow sparser and the temperature rises in places sunlight hits the ground. This is what 24 years of severe drought looks like in the world’s largest rainforest. But this patch of degraded forest, about the size of a soccer field, is a scientific experiment. Launched in 2000 by Brazilian and British scientists, Esecaflor — short for “Forest Drought Study Project” in Portuguese — set out to simulate a future in which the changing climate could deplete the Amazon of rainfall. It is

What does the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) in the Huang Kuo-chang (黃國昌) era stand for? What sets it apart from their allies, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT)? With some shifts in tone and emphasis, the KMT’s stances have not changed significantly since the late 2000s and the era of former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九). The Democratic Progressive Party’s (DPP) current platform formed in the mid-2010s under the guidance of Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文), and current President William Lai (賴清德) campaigned on continuity. Though their ideological stances may be a bit stale, they have the advantage of being broadly understood by the voters.

Artifacts found at archeological sites in France and Spain along the Bay of Biscay shoreline show that humans have been crafting tools from whale bones since more than 20,000 years ago, illustrating anew the resourcefulness of prehistoric people. The tools, primarily hunting implements such as projectile points, were fashioned from the bones of at least five species of large whales, the researchers said. Bones from sperm whales were the most abundant, followed by fin whales, gray whales, right or bowhead whales — two species indistinguishable with the analytical method used in the study — and blue whales. With seafaring capabilities by humans