One could argue that, except for the Internet, the most important technological advance of the past two decades has been hydraulic fracturing, widely known as fracking. Practically overnight, it seems, this drilling technique has produced so much oil and gas beneath American soil that we are at the brink of something once thought unattainable: true energy independence. And its repercussions, for geopolitics, the environment and other areas, are only now being grasped.

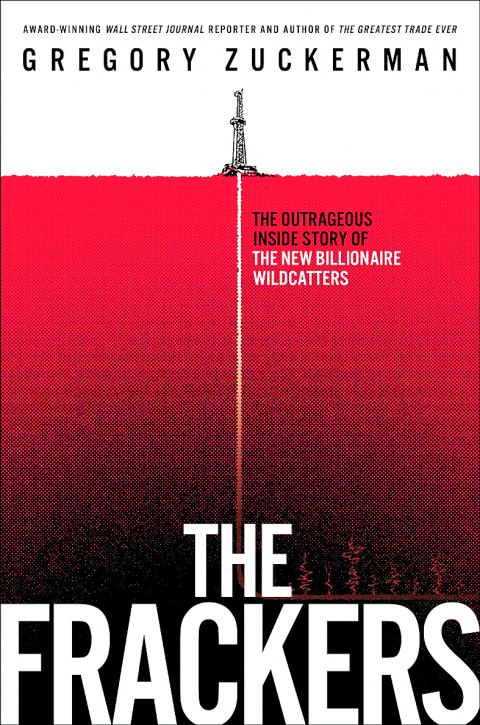

In The Frackers, Gregory Zuckerman sets out a 25-year narrative that focuses on the half-dozen or so Texas and Oklahoma energy companies behind the fracking boom, especially Chesapeake Energy, the Oklahoma City giant that is the Exxon Mobil of fracking. Technologies are born. Gushers gush. And fortunes are made and lost.

In the process, Zuckerman assembles a chorus of little-heard American voices, from George Mitchell, the Greek goatherd’s son whose company first perfected fracking, to Chesapeake’s two founders, Aubrey K. McClendon and Tom L. Ward. Yet despite this, The Frackers doesn’t quite end up being memorable music, at least not to these ears. Much of this has to do with literary shortcomings that, while relatively minor, are the difference between this being an “A-plus” book and the “B-plus” book it is.

Fracturing solid rock to free the oil trapped inside, it turns out, is nothing new. It was first tried by a Pennsylvania driller all the way back in the 1860s. Just as the Internet boom was driven by the discovery and marriage of two technologies — digitization and broadband delivery — so, too, has the new energy bonanza been driven by parallel advances in fracking and in horizontal drilling — that is, wells that are drilled down into the earth and then turned sideways to reach oil- and natural-gas-bearing strata. The difference between vertical and horizontal drilling is the difference between gathering up a fistful of thrown sand with a straw versus a spatula.

What changed everything was the unleashing of these new techniques on a notoriously unyielding kind of subterranean rock called shale. Geologists knew that layers of shale spread across North America contained commercial amounts of oil and gas, but not until a young geologist at Mitchell’s company, Mitchell Energy, perfected a new “secret sauce” of water-based fracturing liquids in the early 1990s did layers of shale — in Mitchell’s case, the Barnett Shale of North Texas — melt away and begin to yield jaw-dropping gushers.

Oryx Energy, a company that was based in Dallas, was among the first to pair fracking with horizontal drilling, producing even more startling results. Still, it took years, Zuckerman writes, before larger businesses, especially the skeptical major oil companies, fathomed what their smaller rivals had achieved. This allowed what were flyspeck outfits like Chesapeake to lease vast acreage in shale-rich areas, from Montana to eastern Pennsylvania.

Zuckerman is a reporter for The Wall Street Journal who had a well-received first book, The Greatest Trade Ever, about the wildly lucrative bet of the hedge fund manager John Paulson against the housing market. The Frackers, his second book, is told with care and precision and a deep understanding of finance and corporate politics as well as oil and geology. Any criticisms I have of it are akin to those aimed at a .290 hitter who ought to be hitting .335. That said, too much of the The Frackers reads like a very long Wall Street Journal article.

A book, unlike a newspaper article, has more room to make people and places come alive, and this is the biggest disappointment of The Frackers. I read a hundred pages about Mitchell Energy, but I couldn’t tell you what its headquarters looked like. Neither of Chesapeake’s founders, McClendon or Ward, springs off the page, either. The book is littered with characters whose physical appearances are described in a phrase or two at best.

Throughout, Zuckerman maintains a laser-like focus on the fracking companies and their top executives. This results in what I call conference-room history; I can’t remember a single scene set around an actual well, or even a single description of one.

Tangents repeatedly, and strangely, slither into corners of executives’ personal lives. And the author doesn’t spend much time examining the potential environmental impacts of fracking, which are relegated to the end of the book. What he says is dismissive, and should be explored further.

Zuckerman may have yet to find his true voice, but his book is nonetheless a cut above others of its type. The Frackers is a good, solid read for anyone interested in fracking or the oil and natural gas industry. And for all my reviewer-ish carping, I’ll be among the first to buy his next offering.

Following the shock complete failure of all the recall votes against Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers on July 26, pan-blue supporters and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) were giddy with victory. A notable exception was KMT Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫), who knew better. At a press conference on July 29, he bowed deeply in gratitude to the voters and said the recalls were “not about which party won or lost, but were a great victory for the Taiwanese voters.” The entire recall process was a disaster for both the KMT and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). The only bright spot for

Water management is one of the most powerful forces shaping modern Taiwan’s landscapes and politics. Many of Taiwan’s township and county boundaries are defined by watersheds. The current course of the mighty Jhuoshuei River (濁水溪) was largely established by Japanese embankment building during the 1918-1923 period. Taoyuan is dotted with ponds constructed by settlers from China during the Qing period. Countless local civic actions have been driven by opposition to water projects. Last week something like 2,600mm of rain fell on southern Taiwan in seven days, peaking at over 2,800mm in Duona (多納) in Kaohsiung’s Maolin District (茂林), according to

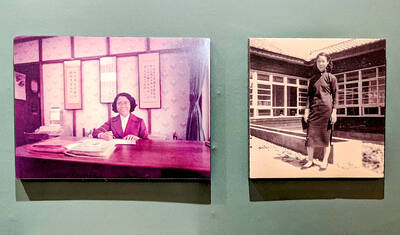

Aug. 11 to Aug. 17 Those who never heard of architect Hsiu Tse-lan (修澤蘭) must have seen her work — on the reverse of the NT$100 bill is the Yangmingshan Zhongshan Hall (陽明山中山樓). Then-president Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) reportedly hand-picked her for the job and gave her just 13 months to complete it in time for the centennial of Republic of China founder Sun Yat-sen’s birth on Nov. 12, 1966. Another landmark project is Garden City (花園新城) in New Taipei City’s Sindian District (新店) — Taiwan’s first mountainside planned community, which Hsiu initiated in 1968. She was involved in every stage, from selecting

As last month dawned, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was in a good position. The recall campaigns had strong momentum, polling showed many Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers at risk of recall and even the KMT was bracing for losing seats while facing a tsunami of voter fraud investigations. Polling pointed to some of the recalls being a lock for victory. Though in most districts the majority was against recalling their lawmaker, among voters “definitely” planning to vote, there were double-digit margins in favor of recall in at least five districts, with three districts near or above 20 percent in