Samuel Coleridge’s celebrated Ancient Mariner may have suffered remorse over the death of an albatross, but today’s reality is that 100,000 albatrosses are killed every year — that’s one every five minutes — mostly on the baited lines of modern industrial-scale fishing vessels. At this rate, extinction is all but inevitable.

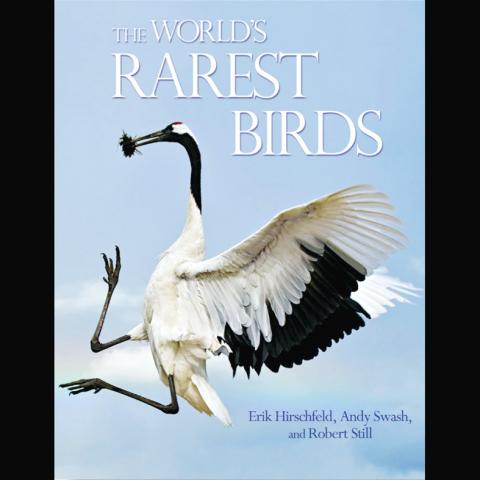

The title of this book, The World’s Rarest Birds, may sound as if it’s announcing an account of exotic avian species living in happy isolation far from the eyes of man. There are indeed some such cited here, but for the most part this is an illustrated catalog of species that have suffered so disastrously from what we’re pleased to call “development” that they’re now coming close to final disappearance.

The extinction of any creature is a form of tragedy. It has evolved over millions of years, and is unique in the universe. Yet, often in a relatively short period of time, a combination of factors, almost always related to human activity, renders its continued existence impossible. The last specimen silently dies, and all but the most dedicated professionals, and maybe a few locals, are wholly unaware of its demise.

There are believed to be 27 of New Zealand’s Black Stilts in existence, whereas the total for Hawaii’s Oahu Alauahio is given here as anything from one to seven. Many species are listed as possessing fewer than 50 individuals (and this is not taking into account 60 species about which so little is known that they’re listed as “data deficient”). It’s hard to know which is more extraordinary, the plight of these creatures or the dedication of the individuals who are able to come up with such precise numbers.

The purpose of this magnificent book is to catalog all these threatened species. It’s striking on two counts — its detailed information and its illustrations. All 650 species are illustrated either by a photograph or, in 76 cases where no photograph exists, by a painting based on the bird’s known characteristics. The photos are the work of over 300 enthusiasts who responded to a competition sponsored by, among others, the quality optics company Minox.

One thing is absolutely clear — the responsibility for the threat to these precious species is ours. Whether it’s hunting, logging, the international trade in exotic species, the destruction of wetlands, industrial-scale fishing, the introduction of previously unknown mammals such as rats and feral cats, dams, pollution, residential development, mining, man-made climate change, or war, we are exclusively and culpably the villains.

About 130 bird species have become extinct since 1500, with a current total of 9,934 living species recognized by BirdLife International, the conservation-coordinating authority responsible for this book. Of these, 197 are considered as Critically Endangered (i.e. near to extinction), while 389 are Endangered, the next category down this list.

Yet everywhere there are groups, listed here, dedicated to helping these creatures, breeding them in captivity where possible when numbers are low, for example, and then releasing them back into the wild. The Syrian Society for Conservation of Wildlife (SSCW) is, I’m pleased to see, included in the list.

Broader measures can also be put into place. Take the albatross again. These fabulous, slow-breeding birds are major victims of the international fishing industry, with most of them dying on the baited hooks of longline fishing vessels. Yet simple, inexpensive measures can reduce this toll almost to nothing.

In one area south of Chile, for example, dyeing the bait blue, attaching pennants to lines and weighting hooks so they sink faster reduced albatross deaths to zero, when it had previously been 1,500 birds per year. Taiwan has a huge pan-global fishing fleet; let’s hope these measures are already in place on all their longline boats.

It so happens that Asia is now experiencing the fastest environmental degradation of areas vital to birdlife. Fifty million birds a year use the migration route known as the East Asian-Australasian Flyway, which runs from eastern Siberia down to Australia and New Zealand. Wetlands, where the migrants rest and feed, are crucial.

The fate of South Korea’s Saemangeum estuary area offers a terrible warning. Now enclosed by a sea wall, its formerly abundant molluscs and crabs have disappeared, and the effect on migratory bird numbers has been catastrophic. According to this book, over 80 percent of East and Southeast Asia’s wetlands are similarly threatened.

Sometimes a combination of inaccessible terrain and political inaction has led to a dismal situation. In the French Overseas Territory of New Caledonia, for example, these authors find that “protected areas … exist on paper only, because of a lack of funding. Some are too degraded for there to be much value in attempting to conserve them, and others are covered by mining concessions.” Elsewhere, political instability deters surveys or conservation work — parts of the Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo are mentioned here in this context.

And yet valiant individuals persist in their efforts. A flightless duck, for instance, on Campbell Island, far to the south of New Zealand, was for 30 years thought to be extinct due to the introduction of rats until, in 1975, a tiny group was discovered on a rat-free island nearby. Four specimens were taken to New Zealand and bred in captivity, then introduced back onto Campbell Island itself, where the rats had been eradicated. A population of between 100 and 200 is now breeding there in a variety of habitats. The great California Condor was similarly saved.

All praise must go to the thousands of bird-lovers and careful experts, often dedicated amateurs, who’ve unknowingly contributed to this magnificent but troubling book. Princeton University Press has done a wonderful job in creating an authoritative volume that’s also a delight to hold, even if it’s frequently disturbing to read.

But it’s the kind of book that people who’re lucky enough to possess a copy will use for reference. Let’s hope that at least sometimes they will reach for it to check out a species that has been at the last minute saved from the brink, and not always to cross out the entry for one that — faced with the cruelties of the modern world — just hasn’t managed to make it.

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) hatched a bold plan to charge forward and seize the initiative when he held a protest in front of the Taipei City Prosecutors’ Office. Though risky, because illegal, its success would help tackle at least six problems facing both himself and the KMT. What he did not see coming was Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (將萬安) tripping him up out of the gate. In spite of Chu being the most consequential and successful KMT chairman since the early 2010s — arguably saving the party from financial ruin and restoring its electoral viability —

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,