This collection of eight short stories by the author of I Love Dollars [reviewed in the Taipei Times Feb. 11, 2007] poses several problems, not the least of which is that it takes a considerable degree of determination to struggle through it.

In one way, this is strange. All the stories are tightly constructed, and the English translation, by Julia Lovell, is quite exceptionally fluent. Zhu Wen’s (朱文) wit and outspokenness are undiminished. I nevertheless felt an unease while reading the book that has taken me some time to account for.

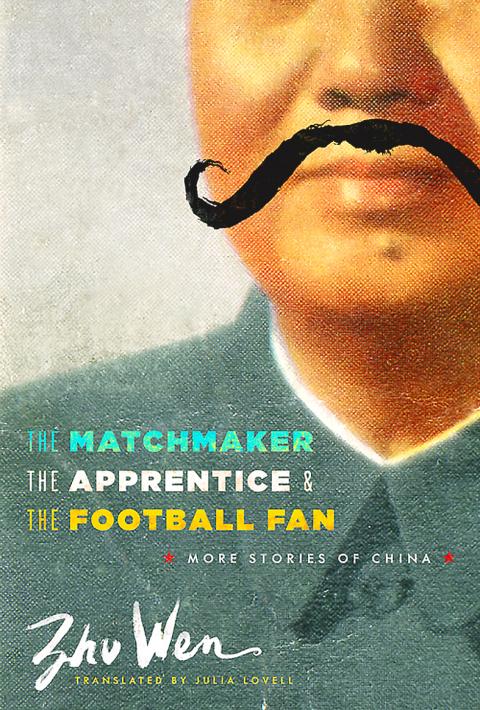

The title story of I Love Dollars was characterized by a rampant sexuality and absurdity. The volume’s other stories contributed to the portrayal of China as a country that was far gone in the process of losing its way in a maze of commercialism. Seven years on, the publishers at Columbia University Press call the stories in The Matchmaker, The Apprentice, and The Football Fan “socialist gothic,” and describe Zhu as a “fearless commentator on contemporary China.”

The problem with this last claim is that all these stories bar one were published in Chinese in the 1990s. (The final story, The Wharf, came out in 2009). China has changed a lot since then. Nor is this all. Another trouble with the assertion is that Zhu appears to have given up writing fiction, and now devotes his energies largely to film-making.

Da Ma’s Way of Talking opens the new volume. It’s a somewhat slight tale of a young man (the narrators of all the stories except two are young men) who is driven mad by discovering that a string of his friends, including his girlfriend, talk in the manner of a former student he’d known but that the others couldn’t possibly have met. It transpires the student in question was killed on the road to Tibet, but for the rest the mystery is nowhere satisfactorily explained.

The Matchmaker follows, the story of another young man looking for a girlfriend while conducting an affair with a married woman. An unusual feature is that their relationship is characterized by protracted quotations from Hamlet, made absurd by the actor being represented as continually smoking cigarettes. Smoking is one of Zhu’s obsessions.

Next comes The Apprentice, an ironic and hard-hitting account, scatological in places, of someone starting work in a factory where his co-workers are given to swearing, drinking and cursing the leadership of both the factory and the country as a whole. They’re also addicted to table-tennis and playing cards, two forms of passing the time that lead to the story’s absurdist plot-resolution.

What I found myself thinking while reading these and later tales was that, while they were clearly intended to be comic, and surely were comic in their original Chinese when read by citizens of the 1990s PRC, I was not doubling over with laughter. But I don’t expect Michael Moore or Will Self are particularly funny in Chinese either. Of all literary genres, comedy seems to me the one that travels the least well.

On the other hand, I Love Dollars was funny enough. So if comedy can indeed travel in the right circumstances, and Zhu’s comedy at that, how are we to explain the relative plainness of this new collection? The obvious answer is that the author no longer has his heart in the story-telling business.

A pointer to this conclusion is that this time translator Julia Lovell provides no introduction. Her introduction to I Love Dollars was outstanding, but this time she prefers to say nothing. Maybe she feels that she’s said it all before, but it’s also possible she senses these stories are less good and prefers to keep her mouth shut. She’s a lecturer in modern Chinese history in the University of London, and readers will perhaps remember that she is author in her own right of The Opium War, reviewed in the Taipei Times on Oct. 2, 2011.

A further indication of this book’s relative shortcomings is that the great Chinese scholar Jonathan Spence, who provides an endorsement, says that these stories are “both darker and denser” than those in Zhu’s first book. This could be a coded way of getting round the undoubted fact that they are simply less funny.

The story Spence chooses as memorable is Mr. Hu, Are You Coming Out to Play Basketball This Afternoon? This is a very clever plot-driven tale about a man who adopts the child of a woman he once found very attractive. What finally occurs can perhaps be guessed, but the story is told without hint of censure, and is indeed something in the way of a small masterpiece.

Other items include Reeducation, an extended political satire set in the years after the Tiananmen Square Massacre of June 1989, the bleak and formal The Football Fan about a youth who claims to be both gay and a small-time thief — all the six sections of which begin with the identical paragraph — and The Wharf, set in Tibet and featuring the indigenous Zangxiang breed of pigs.

This leaves only Xiao Liu, a rather convoluted but nevertheless major story. It has two thematic parts, one set in Harbin and featuring the narrator’s obsession with a woman of partly Russian ancestry, the other set in Nanjing and involving the aforesaid Xiao Liu who’s both a suspected spy on the narrator’s Fujian-dialect-speaking mother, and a computer freak and genuinely good friend of the family. This kind of paradox is quintessential Zhu. He probably thinks that being both a writer and a film director is equally paradoxical, but delights in the situation nonetheless. Should he read this less-than-rave review, he’ll probably take it with a laugh and quick aside on the essential absurdity of the non-Chinese-speaking world — not to mention the Chinese-speaking one as well.

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the

Six weeks before I embarked on a research mission in Kyoto, I was sitting alone at a bar counter in Melbourne. Next to me, a woman was bragging loudly to a friend: She, too, was heading to Kyoto, I quickly discerned. Except her trip was in four months. And she’d just pulled an all-nighter booking restaurant reservations. As I snooped on the conversation, I broke out in a sweat, panicking because I’d yet to secure a single table. Then I remembered: Eating well in Japan is absolutely not something to lose sleep over. It’s true that the best-known institutions book up faster

Though the total area of Penghu isn’t that large, exploring all of it — including its numerous outlying islands — could easily take a couple of weeks. The most remote township accessible by road from Magong City (馬公市) is Siyu (西嶼鄉), and this place alone deserves at least two days to fully appreciate. Whether it’s beaches, architecture, museums, snacks, sunrises or sunsets that attract you, Siyu has something for everyone. Though only 5km from Magong by sea, no ferry service currently exists and it must be reached by a long circuitous route around the main island of Penghu, with the