THE BLESSED UNREST

Sara Bareilles

Epic

Sara Bareilles sings Manhattan with heavy exhaustion, like a woman beaten down by the marathon she’s just finished. “You can have Manhattan, I know it’s for the best,” she exhales, over a dark, slow-moving piano, redolent of the early, elegantly pugnacious Billy Joel. “I’ll gather up the avenues and leave them on your doorstep/And I’ll tiptoe away so you won’t have to say you heard me leave.” She’s not snide or colorfully melodramatic — just spent.

That’s the fourth song on The Blessed Unrest, her new album, and it speaks loudly. It especially shouts down the songs that precede it, which — including the single Brave — are booming and jangly, songs that announce in scale what Bareilles’ sweet and sometimes nervy voice doesn’t always do on its own.

Still, it’s a surprise that Bareilles’ best song on this album is her most morose. She’s never matched the pep of her 2007 debut single, Love Song”a song about what sort of song she’s unwilling to write. That theme — writing about writing — re-emerges on the first couple of songs of this album, like an early college writing experiment.

The album is suffused with that kind of seriousness — not the emotional sort, as on Manhattan, but the stylistic sort. Worse, The Blessed Unrest isn’t as smilingly eclectic as her better earlier work, especially the often masterly Kaleidoscope Heart, from 2010. Those albums bore traces of cabaret, girl-group pop, college a cappella groups — a whole host of future karaoke repertory — and were built around Bareilles’ good cheer, which buoys her even in down moods.

Bareilles is hiding behind styles that aren’t her own. Only on Little Black Dress does that strategy pay off. It sounds like an Amy Winehouse sketch, with a zippy horn-led arrangement. Vocally, Bareilles sounds bright, too, and comfortable — doing her familiar trick of making the melancholy chirp.

— JON CARAMANICA, NY Times News Service

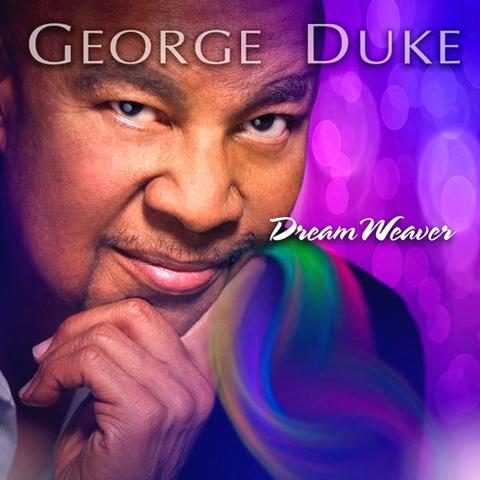

DREAMWEAVER

George Duke

Heads Up International

Tucked away near the end of George Duke’s new album is a track called Burnt Sausage Jam, which sprawls out over an intense and soulful 15 minutes. Featuring Duke on keyboards, Jef Lee Johnson on guitar, Christian McBride on electric bass and John Roberts on drums, it’s an in-the-pocket tune that meanders to a few unexpected places. It has an abrupt beginning, a false ending and a convincingly live feel, down to the crisp solos from all involved. It’s unfocused but oddly riveting — and that’s before it segues into the album’s straight-faced valediction, a gospel cover of Happy Trails.

There’s reason to cheer any sign of loose digression from Duke, who at 67 has comfortably settled into his role as a sage of jazz-funk, smooth R&B and various other crossover hybrids. DreamWeaver is a typically all-over-the-map effort for him, complete with a post-Parliament freakout jam (Ashtray), some cooled-out cosmic fusion (Brown Sneakers) and a smoldering near-bossa nova (Stones of Orion). A track called Trippin’ has him singing about his early exposure to jazz, in what feels partly like a testimonial and partly like a therapy session.

DreamWeaver is Duke’s first album since the death of his wife, Corine, last year. That loss hangs heavily over Missing You, a slow jam with Rachelle Ferrell on lead vocal, which begins with an uncomfortably earnest voice-over by Duke.

A bit less wrenchingly, the album also pays tribute to Johnson, the guitarist, who died this year, and the soul and R&B singer Teena Marie, who died in 2010. A track called Ball & Chain represents one of Marie’s final recordings, and despite some indifferent lyrics, it’s a strong and sinuous performance; Duke is good at making those happen.

He’s a little less good at filtering out the clunkier aspects of his music. The low point here is a treacly pop ballad called Change the World, featuring a small army of guest vocalists, like BeBe Winans, Lalah Hathaway and Freddie Jackson. (There’s no danger of confusing it with the identically titled Eric Clapton hit, or with Michael Jackson’s Heal the World.) Nearly as cringeworthy, for different reasons, is Round the Way Girl, which casts Duke as a leering old man.

So skip those, and seek out the moments on DreamWeaver that ratify Duke’s mastery with vintage synthesizers: a Prophet 5, an Arp Odyssey, a Minimoog, a clavinet. Or head straight to a Latin ballad called You Never Know, which illuminates his stature among next-wave fusionistas like Thundercat and Flying Lotus. Duke does some of his best singing on that track, in a breathy but urgent falsetto, and his message of uncertainty is poignant. “Embrace the cold, go through the rain,” he sings. “Accept the things we cannot change.”

— NATE CHINEN, NY Times News Service

TRIALS & TRIBULATIONS

Ace Hood

We the Best/Cash Money/Universal Republic

There’s been no greater act of hip-hop bandwagoneering this year than Ace Hood’s Bugatti. It’s a surge of triumphalism from a rapper who doesn’t appear to have earned it, but what carries the song is the hook, by Future, which sounds as if it were melting out of the speakers, in that characteristic Future way. This isn’t Future at his most creative, but the digitally decaying voice is there — it’s a gift, and it does the work so that Ace Hood doesn’t have to.

The result is Ace Hood’s biggest hit in a five-year career, and what does he do with the currency that a success of this scale has earned him? Unexpectedly, he makes the most socially conscious mainstream rap album of the year thus far.

Granted, this is a preposterously low bar in 2013. The end-zone dance that is Bugatti is far more in keeping with hip-hop’s prevailing mood, and half of this album tries to match it but falls short. But most of the rest of Trials & Tribulations is far darker and more reflective — it’s music for bad moods and self-doubt. Turns out that Ace Hood is obsessed with poverty, redemption, broken families, religiosity, Trayvon Martin and Emmett Till. Plenty of rappers give lip service to the same things, but usually as a means to celebrating overcoming long odds. On songs like Another Statistic, Hope and The Come Up, Ace Hood sounds happy to be mired in the difficult stuff. They sound as if they were teleported in from the early 1990s, when there wasn’t shame in struggle.

But while Ace Hood is occasionally a nimble rapper, he’s rarely an effective one. He raps quickly in a thick, gluey voice, with little tonal variance, like endlessly striking one key on the piano. This is his fourth album, a milestone many better rappers haven’t reached, but he has the blessing of powerful benefactors: DJ Khaled, to whose label he is signed, and now the Cash Money cartel, including Birdman and Lil Wayne.

Perhaps without that baggage he’d be received as a more complex figure, something other than a mere minor leaguer looking to graduate to the bigs. But it’s only that baggage that’s gotten him this far. After all, all moguls need charitable write-offs.

— JON CARAMANICA, NY Times News Service

Following the shock complete failure of all the recall votes against Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers on July 26, pan-blue supporters and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) were giddy with victory. A notable exception was KMT Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫), who knew better. At a press conference on July 29, he bowed deeply in gratitude to the voters and said the recalls were “not about which party won or lost, but were a great victory for the Taiwanese voters.” The entire recall process was a disaster for both the KMT and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). The only bright spot for

Water management is one of the most powerful forces shaping modern Taiwan’s landscapes and politics. Many of Taiwan’s township and county boundaries are defined by watersheds. The current course of the mighty Jhuoshuei River (濁水溪) was largely established by Japanese embankment building during the 1918-1923 period. Taoyuan is dotted with ponds constructed by settlers from China during the Qing period. Countless local civic actions have been driven by opposition to water projects. Last week something like 2,600mm of rain fell on southern Taiwan in seven days, peaking at over 2,800mm in Duona (多納) in Kaohsiung’s Maolin District (茂林), according to

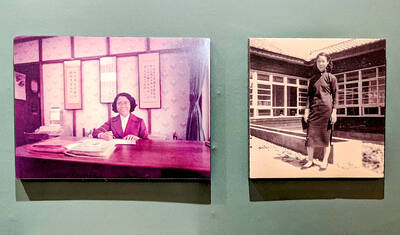

Aug. 11 to Aug. 17 Those who never heard of architect Hsiu Tse-lan (修澤蘭) must have seen her work — on the reverse of the NT$100 bill is the Yangmingshan Zhongshan Hall (陽明山中山樓). Then-president Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) reportedly hand-picked her for the job and gave her just 13 months to complete it in time for the centennial of Republic of China founder Sun Yat-sen’s birth on Nov. 12, 1966. Another landmark project is Garden City (花園新城) in New Taipei City’s Sindian District (新店) — Taiwan’s first mountainside planned community, which Hsiu initiated in 1968. She was involved in every stage, from selecting

The latest edition of the Japan-Taiwan Fruit Festival took place in Kaohsiung on July 26 and 27. During the weekend, the dockside in front of the iconic Music Center was full of food stalls, and a stage welcomed performers. After the French-themed festival earlier in the summer, this is another example of Kaohsiung’s efforts to make the city more international. The event was originally initiated by the Japan-Taiwan Exchange Association in 2022. The goal was “to commemorate [the association’s] 50th anniversary and further strengthen the longstanding friendship between Japan and Taiwan,” says Kaohsiung Director-General of International Affairs Chang Yen-ching (張硯卿). “The first two editions