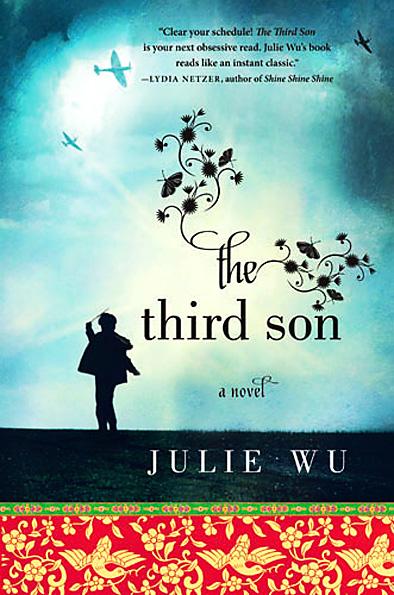

Make no mistake about it, this is a really excellent novel. I don’t say this because, at least in the early chapters, it’s set in Taiwan. Nor is it because the narrator is a native of Taoyuan. The Third Son is wonderful in the ways most really good novels are wonderful, reasons that I will attempt to elucidate below.

The story begins in 1943 when US planes were targeting Taiwanese citizens because the island was a colony of the Japanese empire. The eight-year-old Saburo — his Japanese name; his Chinese name is Chia-lin — protects a fellow student, Yoshiko, and thereafter determines one day to marry her.

But he’s a third son, and as such receives scant attention in his highly traditional Taiwanese family. His arrogant and untalented elder brother, Kazuo, gets the best of everything, and in addition sets his sights on Yoshiko before the story has gone very far.

But Saburo is highly motivated, learning from books what he doesn’t get taught at his unremarkable schools. He soon finds his way to the post-war US where he pursues his ambition to enter the burgeoning field of space rocket technology.

What makes this novel so remarkable isn’t, as some Taiwan enthusiasts have claimed, that it contains descriptions of crucial events in Taiwanese history such as the arrival of the first Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) troops from China, the 228 Massacres, and the subsequent White Terror. These are all afforded somewhat cursory treatment. The least important of the many aspects of the book that make it compulsive reading is the sophistication of its plotting, and the way the author keeps you hooked with the last sentence of virtually every chapter.

Much more importantly, she develops not only the plot, but also themes. The main one of these is the terrible sadness brought on by the traditional, and one hopes nowadays old-fashioned, Chinese family ethos.

“A wound that never healed. A promise never to be fulfilled. That was family.” So concludes Saburo towards the book’s end. And this, as a judgment on the traditional Chinese family, is the burden, the deep ground-swell, of this fine novel.

But things aren’t that simple. It isn’t giving away too much of the plot to say that Saburo succeeds in marrying Yoshiko quite early on in the tale, but because he’s away studying in the US, initially alone, he fails to establish any significant relationship with his young son, Kai-ming. Thus history threatens to repeat itself, with Saburo on the edge of becoming the remote and, in the eyes of his offspring, unfeeling father that his own father had unambiguously been before him.

Nonetheless, the general tone of the novel isn’t melancholy but buoyant and optimistic. Saburo repeatedly overcomes the problems that so frequently confront him, winning scholarships, becoming the first Taoyuan boy ever to study in the US, becoming an assistant to a cutting-edge professor at Ann Arbor, Michigan who’s specializing in rocketry, and so on. The background to the second half of the novel, incidentally, is the Russian success in launching the first artificial satellite, Sputnik, into space in 1957.

In addition to plot and theme, a good novel is said to have believable and well-defined characters. These The Third Son certainly has. Kazuo is particularly loathsome, as is, though in a different way, Saburo’s father. And Yoshiko is excellently portrayed as the virtuous girlfriend, the kind of person who would rather have a good-natured, idealistic man for a husband than any amount of material wealth.

Of course, the eventual success of a despised younger son isn’t a new plotline in the long history of the Western novel. Henry Fielding was perhaps the first to use it in his masterpiece Tom Jones, where Tom, initially thought to be a foundling, gets the better of his detestable sibling, the legitimate Blifil. But this doesn’t prevent the device working well once again here.

I also warmed to this novel for reasons additional to the above. There is something about Julie Wu’s clear and concise style that displays, too, an emotional honesty. That is certainly the quality she most admires in Saburo, and, for that matter, Yoshiko. But the author’s wanting goodness to prevail, yet of necessity having to construct obstacles in its path, made me smile on a number of occasions, but invariably with pleasure and never, I hope, with condescension.

The novel has other riches, too. The political theme, for instance, goes a lot further than the portrayal of the emaciated KMT troops, saucepans tied round their necks, who were the first Nationalists to arrive on Taiwanese shores. Nationalist agents are there in the US as well, trailing Saburo and very nearly upsetting his carefully-nurtured plans. Politics also continue to influence lives back in Taiwan. Indeed, Taiwanese history is presented as being a sequence of acts of possession and control by alien powers, of which the Chinese Nationalists are merely the most recent.

The author doesn’t say so, but the two main themes are linked. Asian governments seeking to avoid implementing Western-style human rights legislation often plead the situation is different here, citing “Asian family values.” The irony, and absurdity, of this will be clear to anyone reading this book.

Julie Wu writes that she made a point of listening to her parents in order to understand the realities on the ground of the wartime, and then post-war, years in Taiwan. She also consulted the relevant experts in the US, where she lives, on relevant aspects of space technology in the 1950s.

This novel, then — which came out in hardback last week — is highly recommendable. In fact, in my judgment it’s the best novel featuring Taiwan I’ve ever read. A few others have perhaps more thoroughly worked up particular incidents in depth, but none has been as professionally constructed and as lucidly written as The Third Son. In short, you’d have to be a die-hard KMT supporter, or an enthusiast for traditional Taiwanese family values, not to find this book a fantastically good read.

Ahead of incoming president William Lai’s (賴清德) inauguration on May 20 there appear to be signs that he is signaling to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and that the Chinese side is also signaling to the Taiwan side. This raises a lot of questions, including what is the CCP up to, who are they signaling to, what are they signaling, how with the various actors in Taiwan respond and where this could ultimately go. In the last column, published on May 2, we examined the curious case of Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) heavyweight Cheng Wen-tsan (鄭文燦) — currently vice premier

On Facebook a friend posted a dashcam video of a vehicle driving through the ash-colored wasteland of what was once Taroko Gorge. A crane appears in the video, and suddenly it becomes clear: the video is in color, not black and white. The magnitude 7.2 earthquake’s destruction on April 3 around and above Taroko and its reverberations across an area heavily dependent on tourism have largely vanished from the international press discussions as the news cycle moves on, but local residents still live with its consequences every day. For example, with the damage to the road corridors between Yilan and

May 13 to May 19 While Taiwanese were eligible to take the Qing Dynasty imperial exams starting from 1686, it took more than a century for a locally-registered scholar to pass the highest levels and become a jinshi (進士). In 1823, Hsinchu City resident Cheng Yung-hsi (鄭用錫) traveled to Beijing and accomplished the feat, returning home in great glory. There were technically three Taiwan residents who did it before Cheng, but two were born in China and remained registered in their birthplaces, while historians generally discount the third as he changed his residency back to Fujian Province right after the exams.

Few scenes are more representative of rural Taiwan than a mountain slope covered in row upon row of carefully manicured tea plants. Like staring at the raked sand in a Zen garden, seeing these natural features in an unnaturally perfect arrangement of parallel lines has a certain calming effect. Snapping photos of the tea plantations blanketing Taiwan’s mountain is a favorite activity among tourists but, unfortunately, the experience is often rather superficial. As these tea fields are part of working farms, it’s not usually possible to walk amongst them or sample the teas they are producing, much less understand how the