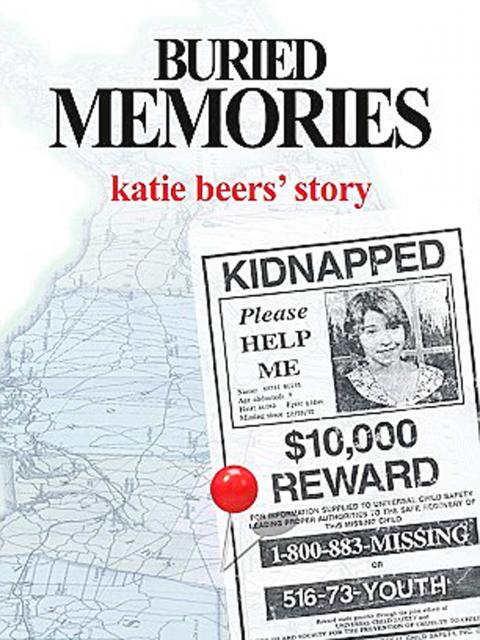

Two decades ago, Katie Beers was a household name, the neglected 9-year-old girl who had been abducted and abused in a dungeon on Long Island.

It is not her married name now, but it is still her story — one that she is now recounting, publicly, with poise and uncommon reflection.

In an interview, Beers, 30, remembered her time in captivity, and how her main thought was of returning home, not knowing that while she was missing, her sad life of neglect and abuse before her disappearance was being unspooled for the nation.

But mostly she reflected on how her life now — as a wife, mother, college graduate and insurance saleswoman — would not have been possible had not the unthinkable happened in 1992.

After avoiding all contact with reporters who once hung on every detail of her case, she is now embarking on a media campaign in an effort to promote a memoir that, she said, had long been in the back of her mind.

‘’From the time I was 10, I wanted to write a book,’’ she said, remembering the taunts of children that made her cry as a girl. “I was tired of the rumors, of people saying, ‘You were held between the walls of this psycho’s house.’”

The reality was perhaps even more chilling.

After luring her to his home with the promise of presents two days before her 10th birthday, a family associate, John Esposito — whom she called Big John — forced Beers down a narrow passageway and into a 6-foot-by-7-foot concrete bunker under his garage in Bay Shore, concealed by a 200-pound concrete trap door.

He kept her there for 16 days, and made her stay, chained by the neck, in a locked wooden box suspended above the ground. A television in the corner provided the only distraction and the only light.

At the time of her disappearance, Esposito, a contractor, had tearfully told the police that he had taken her to an arcade, where she had been kidnapped. He later led the police to his bunker, and said in court that he had built the chamber specifically for her.

In the memoir, written with television reporter Carolyn Gusoff, Beers recounted new details of her early life, including playing in the dirt as Esposito, a contractor, built what would be her cell.

“Big John said it was going to be an underground bunker,” Beers writes. “We were all playing in it, this big open pit in the ground.”

She also said she now recalled being raped by Esposito, though that allegation was never brought up at trial.

Esposito pleaded guilty to kidnapping Beers; prosecutors at the time said the deal spared her from having to testify, but it also meant that three counts of sexual abuse were dropped. He was sentenced to 15 years to life, and is currently housed in Sing Sing prison in upstate New York.

Esposito, in a ghoulish twist, also left a voice-activated tape recorder in the hidden bunker that captured Beers’ calls for help. “Oh please, let me out!” she could be heard screaming, according to a review of the tapes by Gusoff. “Get me out of here!”

The police visited Esposito’s home, but never heard the screams or her attempts to bang on the padded ceiling of her coffin-like confines.

There were significant troubles in Beers’ life long before the abduction.

“My childhood was a thousand times worse than anybody realized,” she said Tuesday.

News accounts at the time portrayed her home life as a kind of Dickensian dystopia a short drive from New York City, with little Katie running around shoeless and performing household chores — like washing laundry at a local coin-operated spot — from the age of 4.

“Before having children, I didn’t realize fully how wrong everything was that happened to me,” she said. “The abuse, the neglect, everything.”

Beers, who took her husband’s name but declined to provide it for reasons of privacy, has two children of her own, a 3-year-old boy and a 17-month-old girl. She said it took her a long time to admit that her own mother, Marilyn Beers, had not provided a stable home for her.

Beers spent much of her youngest years living with her godmother, Linda Inghilleri, who, she writes, treated her as “her slave.” With Beers’ biological father absent since before her birth, Inghilleri’s husband, Salvatore, appeared to be the closest thing to a father figure in her life at the time.

But he too mistreated her, sexually abusing Beers on several occasions. (Inghilleri would later be convicted of that crime. He died in prison in 2009.)

The Inghilleris, who lived in Bay Shore, also continued to allow Esposito to see Beers even after there were suggestions that he had abused her older brother, John.

Beers said she had taken her husband, Derek, to visit Esposito’s home when they were dating, showing him the two-story converted garage where she had been held.

“I wanted him to understand everything,” she said. “Because it’s who I am. It’s what makes me the woman I am today. There’s no point in hiding it.”

After the abduction, Beers lived with a foster family in East Hampton on Long Island who raised her as their own. Her foster father gave her away at her wedding; her children call her foster parents Grandma and Grandpa.

Beers studied business management in college, though for privacy reasons she declined to name the school, and met Derek as a junior while playing pool in a bar.

“He’s very into computers and technology so as soon as he found out my name he went out and Googled me,” she said. “But he never said anything about it until I told him.”

Beers severed most of her ties to her earlier life, though she said she does occasionally talk to her mother, Marilyn.

“I call to tell her the highlights of my life: I’m pregnant; I had the baby; the book is coming out,” she said. “Things like that.”

In an odd way, she said, the kidnapping saved her.

“If the kidnapping hadn’t have happened,” she said, “I don’t even want to think about where I would be, but I would have never graduated high school, I would have never graduated college, I might not even be here, living today, with the road that my life was bound to go down.”

Gusoff, who had covered the story of her kidnapping, approached her in 2008 about doing a follow-up. Beers instead suggested that they write a book. She had already decided she was ready.

“It was right after John’s first parole hearing — I told my dad that I really wanted to start writing the book,” she said.

Beers plans to become an inspirational speaker because, she said, “I want to let people know that no matter what you endure through life, there is something better if you want there to be.”

The Taipei Times last week reported that the rising share of seniors in the population is reshaping the nation’s housing markets. According to data from the Ministry of the Interior, about 850,000 residences were occupied by elderly people in the first quarter, including 655,000 that housed only one resident. H&B Realty chief researcher Jessica Hsu (徐佳馨), quoted in the article, said that there is rising demand for elderly-friendly housing, including units with elevators, barrier-free layouts and proximity to healthcare services. Hsu and others cited in the article highlighted the changing family residential dynamics, as children no longer live with parents,

It is jarring how differently Taiwan’s politics is portrayed in the international press compared to the local Chinese-language press. Viewed from abroad, Taiwan is seen as a geopolitical hotspot, or “The Most Dangerous Place on Earth,” as the Economist once blazoned across their cover. Meanwhile, tasked with facing down those existential threats, Taiwan’s leaders are dying their hair pink. These include former president Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文), Vice President Hsiao Bi-khim (蕭美琴) and Kaohsiung Mayor Chen Chi-mai (陳其邁), among others. They are demonstrating what big fans they are of South Korean K-pop sensations Blackpink ahead of their concerts this weekend in Kaohsiung.

Taiwan is one of the world’s greatest per-capita consumers of seafood. Whereas the average human is thought to eat around 20kg of seafood per year, each Taiwanese gets through 27kg to 35kg of ocean delicacies annually, depending on which source you find most credible. Given the ubiquity of dishes like oyster omelet (蚵仔煎) and milkfish soup (虱目魚湯), the higher estimate may well be correct. By global standards, let alone local consumption patterns, I’m not much of a seafood fan. It’s not just a matter of taste, although that’s part of it. What I’ve read about the environmental impact of the

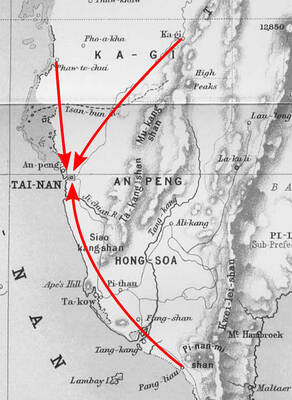

Oct 20 to Oct 26 After a day of fighting, the Japanese Army’s Second Division was resting when a curious delegation of two Scotsmen and 19 Taiwanese approached their camp. It was Oct. 20, 1895, and the troops had reached Taiye Village (太爺庄) in today’s Hunei District (湖內), Kaohsiung, just 10km away from their final target of Tainan. Led by Presbyterian missionaries Thomas Barclay and Duncan Ferguson, the group informed the Japanese that resistance leader Liu Yung-fu (劉永福) had fled to China the previous night, leaving his Black Flag Army fighters behind and the city in chaos. On behalf of the