The story of King Wu Ding (武丁) and Lady Hao (婦好), who ruled the Shang dynasty at its height, had long been the stuff of legend, part of a corpus of works about good rulers embodying the virtues of the ruling class. They were moral exemplars, and their existence was dismissed as mythology by serious academics. This idealized couple came roaring back into the pages of real history following large-scale archaeological excavations in 1928 by the Institute of History and Philology of Academia Sinica (中央研究院歷史語言研究所) at the site of the former capital of the Shang dynasty at modern-day Anyang (安陽), Henan Province.

These excavations proved conclusively that the Shang Dynasty was a fact of history, and suggested that King Wu Ding might be a bit more than just a figure from a mythical golden age. Discovery followed on discovery and the Shang dynasty began to acquire greater historical detail, culminating in 1976 when the Institute of Archaeology at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (中國社會科學院考古研究所) made the remarkable discovery of the undisturbed tomb of Wu Ding’s fascinating consort, Lady Hao, at a palace in modern Xiaotun (小屯).

Many of the artifacts from the earlier excavations were brought over to Taiwan and are in the collection of the Academia Sinica in Taipei, while the rich finds of the later excavations remain in China. King Wu Ding and Lady Hao — Art and Culture of the Late Shang Dynasty (商王武丁與后婦好 ─ 殷商盛世文化藝術) represents the bringing together of artifacts from these two related finds (along with a few bits and pieces from other sources), long separated by later historical developments, and a rounding off of a fascinating story of courtly life in China more than 3,000 years ago.

Photo courtesy of NPM

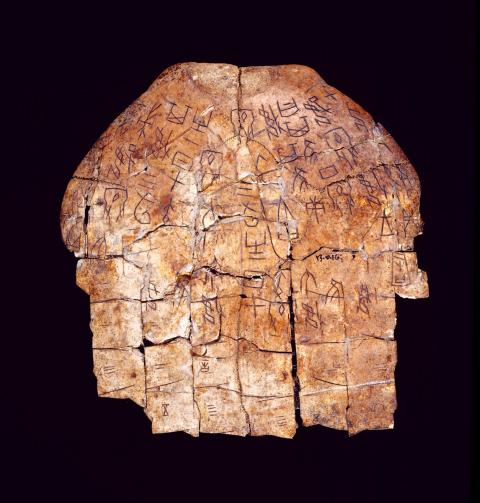

The exhibition organized by City x Culture (雙瑩文創) in coordination with the National Palace Museum, presents a stunning collection of artifacts, from bronze cleaning utensils (a dust pan, identical in shape and function to the plastic versions that can be found at any dollar shop in Taipei is a personal highlight), to highly ornamented ritual vessels, as well as a quantity of oracle bones, used during the Shang for divination, and the earliest examples of the Chinese script, that has continued in an unbroken line of development to the present day.

The oracle bones are some of the most valuable artifacts in existence in the study of early society in China. They are, in fact, not much to look at, and more than anything else, they are a testament to the efforts of scholars who have been able to make sense of the faint etchings on turtle shells and animal bones. The work, closely related to cryptography, has revealed the things that the rulers of Shang felt were important. War and weather rang high in these concerns, but it is also touching to find a question regarding Lady Hao’s toothache. It is this sort of detail that brings the exhibition to life, but the predominant tone of the exhibition is one of exaggerated scholarly reserve.

Lady Hao by all accounts was a most remarkable woman, if the stories are to be believed, taking the role of a war leader against invaders at a time when her royal master was indisposed. Regular references to her on the oracle bones, one of the highest instruments of policy-making in the Shang, reinforce legendary tales of her as a woman of significant resource and power. Vessels of cast bronze with intricate designs and ornaments with turquoise inlay testify to the high level of craftsmanship that had been achieved at the time, and point to a history of aesthetic development dating from a much earlier period.

Photo courtesy of NPM

A rough sketch of a story of this royal couple can be obtained from the printed materials provided in the exhibition, but for those who wish to get into the finer points of Shang culture and the unique place that King Wu Ding and Lady Hao hold, the audio tour (only available in Chinese, NT$100) is highly recommended.

Performance Notes

What: King Wu Ding and Lady Hao — Art and Culture of the Late Shang Dynasty

Photo courtesy of NPM

When: Until Feb. 19, 2013; everyday from 9am to 5pm

Where: Library Building, National Palace Museum (國立故宮博物院圖書文獻大樓), 221, Zhishan Rd Sec 2, Taipei City (台北市至善路二段221號)

Admission: Adults NT$250; children under 110cm tall enter for free

Photo courtesy of NPM

On the Net: Extensive English-language information can be found at chinese-linguipedia.org/wuding/index_En.html

Photo courtesy of NPM

Last week the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) announced that the legislature would again amend the Act Governing the Allocation of Government Revenues and Expenditures (財政收支劃分法) to separate fiscal allocations for the three outlying counties of Penghu, Kinmen and Matsu from the 19 municipalities on Taiwan proper. The revisions to the act to redistribute the national tax revenues were passed in December last year. Prior to the new law, the central government received 75 percent of tax revenues, while the local governments took 25 percent. The revisions gave the central government 60 percent, and boosted the local government share to 40 percent,

Many will be surprised to discover that the electoral voting numbers in recent elections do not entirely line up with what the actual voting results show. Swing voters decide elections, but in recent elections, the results offer a different and surprisingly consistent message. And there is one overarching theme: a very democratic preference for balance. SOME CAVEATS Putting a number on the number of swing voters is surprisingly slippery. Because swing voters favor different parties depending on the type of election, it is hard to separate die-hard voters leaning towards one party or the other. Complicating matters is that some voters are

Sept 22 to Sept 28 Hsu Hsih (許石) never forgot the international student gathering he attended in Japan, where participants were asked to sing a folk song from their homeland. When it came to the Taiwanese students, they looked at each other, unable to recall a single tune. Taiwan doesn’t have folk songs, they said. Their classmates were incredulous: “How can that be? How can a place have no folk songs?” The experience deeply embarrassed Hsu, who was studying music. After returning to Taiwan in 1946, he set out to collect the island’s forgotten tunes, from Hoklo (Taiwanese) epics to operatic

Five years ago, on the verge of the first COVID lockdown, I wrote an article asking what seemed to be an extremely niche question: why do some people invert their controls when playing 3D games? A majority of players push down on the controller to make their onscreen character look down, and up to make them look up. But there is a sizable minority who do the opposite, controlling their avatars like a pilot controls a plane, pulling back to go up. For most modern games, this requires going into the settings and reconfiguring the default controls. Why do they