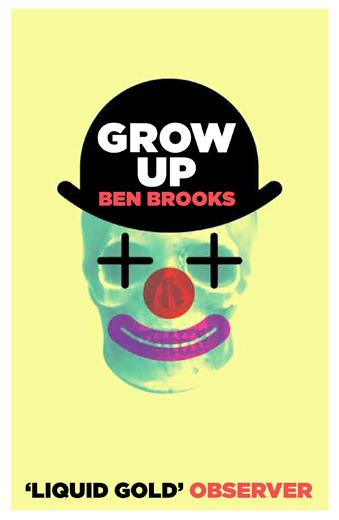

When I started reading this novel about teenage school life in the modern UK, I quickly came to the conclusion that the author, who has three earlier books to his credit, was a smart thirty-something who’d mastered the slang usage of contemporary adolescents, read up about their drug use, was rubbing his hands with glee as he evoked their clumsy sexual antics, and had finally come up with something like a UK re-run of J.D. Salinger’s famous 1951 novel The Catcher in the Rye. There was at least an attempt at a similar insight into adolescents’ doubts and uncertainties behind their superficial bravado. Salinger was a genius of sorts, and his hero, Holden Caulfield, one of the greatest creations of modern US fiction. But Ben Brooks, I considered, had made a not undistinguished stab at something along the same lines for the 21st century.

Then, half way through, I decided to check up on the author online. Imagine my astonishment when I discovered that Ben Brooks was himself 17 when he wrote it. This, then, wasn’t some piece of patronizing literary voyeurism and pastiche, but a report from the front line that surely must contain huge amounts of the writer’s own teenage experience.

But 17! I could hardly believe it. What other example in literature, even using the word in its widest sense, is there of such precocious talent? I was pressed to think of a single instance. And it wasn’t only this novel — Brooks had three earlier works out there as well, published on US-based Web sites.

So — what’s Grow Up like? The title, first of all, is from the rock band Metric’s 2007 song Grow Up and Blow Away, as is made clear towards the end of the book when Jasper Woolf, 17, the narrator, and his school-friends go off to rural Devon and wildly party at a house belonging to some vaguely-related adults. Jasper is someone who’s seen the first Harry Potter film more times than he’s had sex, a statistic he feels he badly needs to reverse.

He lives with his mother and stepfather Keith, someone who, affable though he is, Jasper feels convinced is a murderer. He goes to a somewhat superior school where he appears to study mostly psychology, plus philosophy and religion. He’s clearly going to do well in his exams, in reward for which his mother will let him have a piercing put in his ear, but not, as he wants, in his nose or his penis.

Marijuana unsurprisingly makes frequent appearances, and there’s a long ketamine monologue in which everything is inexpressibly, albeit incongruously, beautiful. But Jasper’s no stranger to mephedrone, especially in conjunction with black Sambuca, coming down from which he reports as feeling like “a pedophile in a nursing home.”

Pedophile jokes are common, incidentally, suggesting that today’s young are unfazed by the topic. Jasper’s class goes on an outing to a Museum of Crime where a former offender addresses them. What do you think I did, he asks. “Pedophile rape!” they all chorus. No, just rape, the poor man replies.

Jasper is a teenager at sea in a world of drugs, school and sex in a shabby, meretricious modern UK. On a coach trip he waits till his friend Ping is asleep, then uses his phone to send “I’m hot for you” texts to all his female cousins. Kettles climax, and he keeps Viagra dissolved in a bottle of Irn-Bru, a carbonated drink.

There’s plenty of writing aimed to impress. A friend’s eyes will be “the eyes of the last Bengal tiger left in Bhutan.” Charity is like putting a plaster on a man with no skin. Another friend’s drugged eyes are so wide he must, Jasper thinks, be imagining his dead grandfather dressed as a woman giving a lap-dance to the Queen.

Then there’s this. “Because Time has been around for a long time, it often gets bored. In order to briefly relieve its boredom, Time enjoys constructing massively unlikely series of events. If these events are of the romantic kind, they are called Fate; if they are of the negative kind, we call them Unfortunate Coincidence.”

In addition there’s a teenage pregnancy, a teenage suicide, and casual sex so frequent that at one point Jasper feels he doesn’t want to hang around to watch it. Drugs, alcohol and tobacco invariably win in the competition with any parental insistence on the need to revise for school exams.

It’s probable that not a lot of this book is invention. In an interview put online by the publishers, Canongate, Brooks admits that “probably everything [in the novel] has happened to me or someone I know,” that he’s quite a lot like Jasper, and that he’ll “do anything to do sex with someone.”

It’s certainly the case that Jasper is described as writing a novel, that he hopes to win the UK’s Booker Prize one day, and that he wishes Haruki Murakami was his stepfather instead of Keith. Brooks also uses the ruse of the author being unambiguously himself when, at the end, he asks to kiss the girl who’s been closest to him throughout. “It’s for my novel,” he says. “It needs character development and resolution.”

But the real coup comes just before that, when out of the blue we’re presented with the following sentence, allowed a paragraph all of its own. “I am Holden Caulfield, only less reckless, and more attractive.”

This, then, is an extraordinary, but nevertheless distinctly self-aware, fictional debut. It may lack depth — it certainly lacks Salinger’s depth — and be over-full of fragmented TV references and one-liners (What are Catholic condoms? Condoms with the ends cut off). But that’s presumably what the mental life of today’s youth in Western countries — and not only Western countries — is actually like.

I doubt very much whether this is an intentional satire on anything — the UK today, for example, grim though that appears. Satire and social comment will probably come later. Indeed, if someone can produce a book like this at 17, who’s to say what he’ll be writing by the time he’s 40?

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) hatched a bold plan to charge forward and seize the initiative when he held a protest in front of the Taipei City Prosecutors’ Office. Though risky, because illegal, its success would help tackle at least six problems facing both himself and the KMT. What he did not see coming was Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (將萬安) tripping him up out of the gate. In spite of Chu being the most consequential and successful KMT chairman since the early 2010s — arguably saving the party from financial ruin and restoring its electoral viability —

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,