It’s a Thursday night in the northern English city of Leeds and people are gathering outside the gay bar Queens Court for a march in support of Russian punk collective Pussy Riot. Maria Alyokhina, Yekaterina Samutsevich and Nadezhda Tolokonnikova are due to be sentenced the following day, the culmination of their trial on charges of “hooliganism motivated by religious hatred.” (For performing their 40-second, Putin-denouncing “punk prayer” in Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Savior in February, they will each receive two years in jail.) In the meantime, this solidarity march is one of many taking place around the world.

Behind a sandwich board, a man changes into a Wonder Woman suit; luminous balaclavas are surreptitiously pulled on as a police video surveillance van lingers in a side road. A woman whose face is covered by a green scarf cries: “It’s been so long since I’ve seen you masked up, darling!” to a megaphone-brandishing woman with the words “moralizing slut” written across her chest (a reference to Russian deputy prime minister Dmitry Rogozin, who called Madonna a moralizing “slut” when she expressed support for Pussy Riot). “I know: since the fucking 90s!” laughs her friend, who turns out to be march organizer Mae Stephens.

There are less-seasoned protestors here, too, among them musicians who have been inspired by the Pussy Riot case. When the march is over and has dispersed to the pub, I ask Wakefield-born protest singer Louise Distras why the punk collective resonate with her.

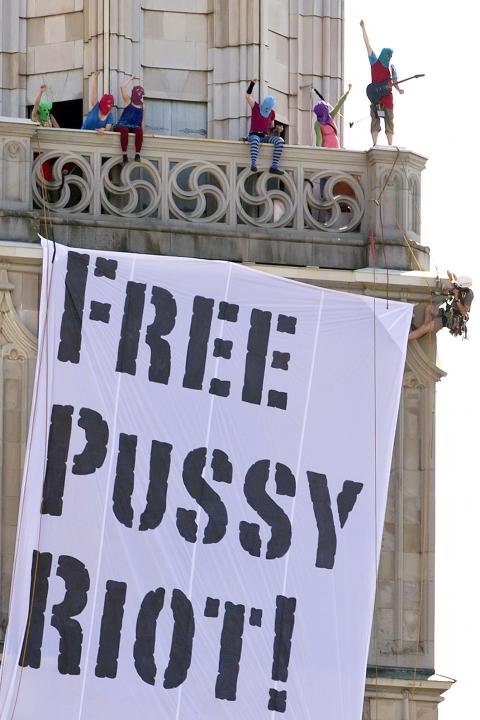

Photo: EPA

“Pussy Riot have inspired me by showing how we absolutely have to speak out against media portrayals of women as subordinates,” she says, “and how it’s very important for female artists to represent other women.” For Distras, the Pussy Riot influence echoes the “riot grrrl” scene of the early 1990s, an underground feminist punk movement that originated in the US. Riot grrrl’s central message has been much debated, but can perhaps best be summed up as a mission to engender communities of supportive, creative women. Certainly, Pussy Riot’s abrasive, energetic sound has much in common with that of the original riot grrrls Huggy Bear and Bikini Kill — though Bikini Kill frontwoman Kathleen Hanna recently cautioned against too literal a reboot of the term. (“Who wants to restart something that’s 20 years old?” she told music website Pitchfork. “This could be a part of a lot of people starting their own fucking thing.”)

The London feminist choir Gaggle are another group who have much in common with Pussy Riot: both are shape-shifting collectives of clever women spreading messages of protest and social awareness, often while wearing brightly colored capes. I asked Gaggle’s founder, Deborah Coughlin, if she thought the trial had started something new. “Riot grrrl still exists, but it’s not the holy covenant of feminist music,” she said. “In fact if anything, I find it restrictive. It’s not fundamentally important that Pussy Riot are musicians, but it is important that we learn from their ideas. They are a living illustration of what needs to change in their country, because we can see them suffering for it.”

Leah Pritchard, singer and guitarist in the Bristol band Empty Pools, has been donating money from sales of her solo material to Pussy Riot’s legal fund via the Web site Bandcamp. (Many other musicians have been doing the same.) Over the phone, Pritchard explains how Pussy Riot are redefining the idea of “honest” artistic expression, something we take for granted in the west. She quotes from Alyokhina’s closing statement to the Moscow courtroom, which in turn quoted from the Russian dissident Vladimir Bukovsky: “How unfortunate is the country where simple honesty is understood, in the best case, as heroism. And in the worst case as a mental disorder.” It shows how little has changed in Russia since the early 1970s, when Bukovsky wrote this.

Photo: EPA

In Australia, the underground music umbrella My Sydney Riot (named before the Russians became famous) have put together a successful fund-raising compilation in aid of Pussy Riot. Founder Ray Lalota says he started My Sydney Riot out of frustration with an oligarchic music industry. “Triple J is an Australian, government-funded, national radio station which gives exposure to a few lucky bands,” he tells me. “They dictate how the industry at large works here. Festival bookers pick bands that are getting national airplay, meaning a lot of independent bands can’t participate, creating a massive gap in the quality of music heard here. To not be allowed to express your art is heartbreaking — but in Pussy Riot’s case, they are fighting for life itself. [Since the case began] I’ve seen new faces at shows and speaking out — we’re all discovering the cultural similarities between Australians and Russians.”

As with any potent symbol of rebellion, there is a risk that the industry will co-opt Pussy Riot’s message in order to make a buck. (There will be a lot of mass-produced posters of the jailed three lining student walls this autumn.) Neil Hanson, frontman of Leeds punk band Kleine Schweine, tells me he is worried that their energy and image will be appropriated. “There’s always the fear that the knock-on effect could be loads of new bands who think that wearing masks and shouting ‘Fuck the system’ is a route to fame. I’m pretty sure major labels are already auditioning for their own Pussy Riot-style money-making band.”

Pussy Riot’s global profile is, of course, an A&R representative’s dream. Bloomberg’s Business Week Web site recently ran a depressing article entitled “What would a music label pay to sign Pussy Riot?” But it’s unlikely Alyokhina, Samutsevich and Tolokonnikova will be signing on any dotted label lines come their eventual release. Will their trial kick-start a Russian punk movement? This seems unlikely. Music journalist Alex Hoban, who has reported from Russia and North Korea for Vice magazine, sees no signs of copycat behavior. “The Russian ‘alternative’ [scene] is marked, sadly, by its complete apathy towards anything other than looking cool. That sounds like a generalization, but really it’s quite shocking. The mainstream right are so vocal and overbearing — after the surge of enthusiasm during the Putin protests earlier in the year, things have quietened down.” He is echoed by Brooklyn psychedelic band (and sisters) Prince Rama, who recently played Moscow; they tell me the conversation there was less about Pussy Riot, more about “Ariel Pink and McDonald’s”.

The music critic Everett True sees in Pussy Riot an opportunity to challenge the male-centric music industry. Emailing from his home in Australia, he tells me: “It’s no coincidence that it’s taken women to effect any major change within the poisoned citadel that is rock ’n’ roll in 2012. Men are such a devalued currency, as Putin and his humorless, protectionist cronies and apologists prove.” He has a point: Pussy Riot have made feminism a vital part of the musical conversation in a year that saw the music magazine NME pan Gaggle’s debut album on the grounds that its members were likely to be open about their menstrual cycles and own books by Germaine Greer.

Back in Leeds, Distras is unequivocal when I ask her whether the Pussy Riot effect could rid the music industry of the prejudice she regularly encounters, even among the supposedly inclusive political set. (At Blackpool’s Rebellion punk festival this August, she says, male performers asked if burlesque dancing was part of her act.) “This is a really good opportunity for people to blow sexism in music and beyond wide open,” she says. “A lot of people think Pussy Riot is a women’s issue. Pussy Riot is the little girl who goes to school and gets told she’s a worthless dyke because she’s more interested in books than boys. Pussy Riot is the little boy who goes to school and gets told to man up when he expresses his emotions. I definitely don’t think this is the end of everything. I think it’s only the beginning.”

May 26 to June 1 When the Qing Dynasty first took control over many parts of Taiwan in 1684, it roughly continued the Kingdom of Tungning’s administrative borders (see below), setting up one prefecture and three counties. The actual area of control covered today’s Chiayi, Tainan and Kaohsiung. The administrative center was in Taiwan Prefecture, in today’s Tainan. But as Han settlement expanded and due to rebellions and other international incidents, the administrative units became more complex. By the time Taiwan became a province of the Qing in 1887, there were three prefectures, eleven counties, three subprefectures and one directly-administered prefecture, with

Taiwan Power Co (Taipower, 台電) and the New Taipei City Government in May last year agreed to allow the activation of a spent fuel storage facility for the Jinshan Nuclear Power Plant in Shihmen District (石門). The deal ended eleven years of legal wrangling. According to the Taipower announcement, the city government engaged in repeated delays, failing to approve water and soil conservation plans. Taipower said at the time that plans for another dry storage facility for the Guosheng Nuclear Power Plant in New Taipei City’s Wanli District (萬里) remained stuck in legal limbo. Later that year an agreement was reached

What does the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) in the Huang Kuo-chang (黃國昌) era stand for? What sets it apart from their allies, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT)? With some shifts in tone and emphasis, the KMT’s stances have not changed significantly since the late 2000s and the era of former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九). The Democratic Progressive Party’s (DPP) current platform formed in the mid-2010s under the guidance of Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文), and current President William Lai (賴清德) campaigned on continuity. Though their ideological stances may be a bit stale, they have the advantage of being broadly understood by the voters.

In a high-rise office building in Taipei’s government district, the primary agency for maintaining links to Thailand’s 108 Yunnan villages — which are home to a population of around 200,000 descendants of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) armies stranded in Thailand following the Chinese Civil War — is the Overseas Community Affairs Council (OCAC). Established in China in 1926, the OCAC was born of a mandate to support Chinese education, culture and economic development in far flung Chinese diaspora communities, which, especially in southeast Asia, had underwritten the military insurgencies against the Qing Dynasty that led to the founding of