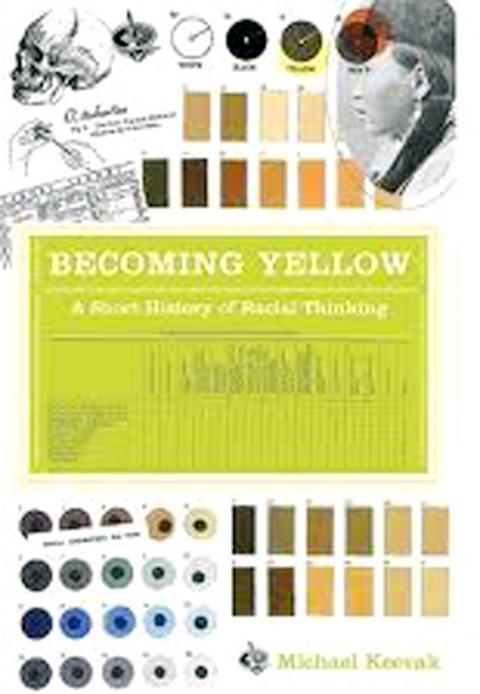

Michael Keevak is a professor at the National Taiwan University who, after his first book, Sexual Shakespeare (reviewed in the Jan. 27, 2002, edition of the Taipei Times), has published books on China and Taiwan-related topics. His new one, Becoming Yellow, is his best to date. It’s an investigation into how East Asians, in particular Chinese and Japanese, came to be perceived as having, to a greater or lesser degree, yellow skin.

It’s an interesting question because, if you think about it for only a moment, it’s clear there’s not the slightest degree of truth in the description.

And that was how Westerners viewed East Asians back in the 18th century, when contact between Europe and Asia first became extensive. The Chinese in particular were then considered simply as white. Of course no people are really white, in the same way that no people are really black, but the term was being applied to Europeans, and the inhabitants of China were considered as of a comparable coloring. So what changed?

The answer is that the West became seized by a compulsion to categorize the inhabitants of the globe into broadly conceived racial groups, and white became reserved for the Europeans who were at that time engaged in a comprehensive exercise in colonization. The people they colonized, therefore, couldn’t be the same as the Europeans were; they had to be different. Whites were destined, so the Europeans managed to convince themselves, to rule the world, and so the people they were destined to rule over had to be something else. Black for Africans and brown for Indians fitted easily enough into this system, but East Asians posed a more difficult problem. When someone came up with the bizarre color yellow, combined with the idea of a widely-dispersed Mongolian race, the twin concepts were welcomed with open arms.

Keevak is always anxious to maintain that there was nothing neutral about this process. Yellow had some negative implications in the West — to be yellow could mean you were cowardly, and yellow journalism meant sensational, unethical journalism. But that was all right as far as the Europeans were concerned, because there always has to be some supposed justification for acts of domination and war, and the perceived yellowness of East Asians fit the bill.

And then, at the end of the 19th century, a neat little alliteration allowed for the emergence of the phrase “the yellow peril,” meaning the threat that the Chinese and Japanese would migrate to the US in such vast numbers that Anglo-Saxon civilization would be overwhelmed. Chinese workers in California following on the Gold Rush, and staying to work on railroad construction at lower rates of pay than the locals, only added fuel to the fire, resulting in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 that wasn’t repealed until 1943.

What kind of book, then, is Becoming Yellow? It’s a tightly-focused look at a narrowly-defined topic, with the period of inquiry from the 17th to the 19th centuries, and representations of yellowness in novels and films specifically excluded. Scare-quotes abound — in one chapter alone I counted 107 instances of single words or two-word phrases placed in quotation marks. Why is this? In some cases they indicate a very short quotation, but it’s obviously most frequently because Keevak wants to distance himself from the racist expressions he so often encounters. It’s a distinguishing characteristic nonetheless, and could be seen to suggest that the author wants to hold at arms’ length whole swathes of past thought and reasoning that don’t accord with modern sensibilities.

Keevak’s ideal appears to be that of almost all politically-correct academics these days, a refusal to see physical differences among the mass of humanity as in any way significant. I, by contrast, positively relish these differences. I agree with Wilfred Thesiger, who once said, when accused of being racist, that he was the opposite, in that of all possible skin-colors he considered white to be aesthetically the least attractive. I agree, and, in this if nothing else, I’m an unrepentant old-fashioned “Orientalist” (scare-quotes notwithstanding).

So what did the peoples designated as yellow think of it all? By and large the Chinese were quite pleased, because yellow had always been an honorable color in their scheme of things, yellow dress for long being reserved exclusively for the emperor. The Japanese were less flattered; they were anxious to distinguish themselves from their Chinese neighbors. They were planning to invade them, and so needed to consider them as different, and of course by implication inferior. The tragic results of this — spurious ideas transforming themselves into real actions — are now all too apparent, as a recent TV feature, Lessons of the Blood, on biological warfare conducted by the Japanese Unit 731 against Chinese villagers in 1942, made abundantly clear.

What is excellent about this book is the author’s close reading of his sources. There are many examples, but two are his pointing out that the concept of yellowness was first applied to Indians, and his observation that the great 18th-century botanist Linnaeus created a category of plants that were narcotic, poisonous or otherwise toxic, and which were characterized by their yellowness.

Keevak cites few books written in Chinese or Japanese, but what should be set against this is that he has trawled through a huge number of European texts in at least six languages. Another admirable characteristic of this book is that it is totally lacking in academic jargon. As for its conclusion, it’s that the concept of East Asians being yellow was pseudo-science from the start, and always a jaundiced fantasy with no basis whatsoever in reality.

Most important of all, however, is that Becoming Yellow covers a topic that appears to have never before been treated in such detail. It will, as a result, be widely read, and those who read it will without any doubt benefit greatly from the experience.

Most heroes are remembered for the battles they fought. Taiwan’s Black Bat Squadron is remembered for flying into Chinese airspace 838 times between 1953 and 1967, and for the 148 men whose sacrifice bought the intelligence that kept Taiwan secure. Two-thirds of the squadron died carrying out missions most people wouldn’t learn about for another 40 years. The squadron lost 15 aircraft and 148 crew members over those 14 years, making it the deadliest unit in Taiwan’s military history by casualty rate. They flew at night, often at low altitudes, straight into some of the most heavily defended airspace in Asia.

This month the government ordered a one-year block of Xiaohongshu (小紅書) or Rednote, a Chinese social media platform with more than 3 million users in Taiwan. The government pointed to widespread fraud activity on the platform, along with cybersecurity failures. Officials said that they had reached out to the company and asked it to change. However, they received no response. The pro-China parties, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), immediately swung into action, denouncing the ban as an attack on free speech. This “free speech” claim was then echoed by the People’s Republic of China (PRC),

Many people in Taiwan first learned about universal basic income (UBI) — the idea that the government should provide regular, no-strings-attached payments to each citizen — in 2019. While seeking the Democratic nomination for the 2020 US presidential election, Andrew Yang, a politician of Taiwanese descent, said that, if elected, he’d institute a UBI of US$1,000 per month to “get the economic boot off of people’s throats, allowing them to lift their heads up, breathe, and get excited for the future.” His campaign petered out, but the concept of UBI hasn’t gone away. Throughout the industrialized world, there are fears that

Like much in the world today, theater has experienced major disruptions over the six years since COVID-19. The pandemic, the war in Ukraine and social media have created a new normal of geopolitical and information uncertainty, and the performing arts are not immune to these effects. “Ten years ago people wanted to come to the theater to engage with important issues, but now the Internet allows them to engage with those issues powerfully and immediately,” said Faith Tan, programming director of the Esplanade in Singapore, speaking last week in Japan. “One reaction to unpredictability has been a renewed emphasis on