When I began this book, called in the US The Time In Between, I assumed it was a blockbuster. These kinds of books have a strange position in the modern world — they’re rarely reviewed, yet they’re what most people read. The reason is almost certainly that reviewers tend to have literary tastes, look down on best sellers, and prefer to review products they think they are going to enjoy and, more importantly, will gain status from reviewing.

But halfway through I was proved to be wrong. Up till then the story of a young woman in Madrid in the 1930s had proceeded at a modest pace, describing her love life, and following her to Spanish Morocco and the city of Tetouan. A dressmaker who loses all her money and more when her typewriter-selling lover tricks her and quickly abandons her, she manages to pay off her debts by becoming couturier to the affluent Germans and elite supporters of General Franco, first in Tetouan and then later back in Madrid.

All this seemed harmless enough, with adventures mixed with problems solved, and all in an attractively exotic period setting. Then it dawned on me that several of the major characters were actually real-life figures, and prominent players in Spanish politics in the period between the end of the Spanish Civil War and the outbreak of World War II. There’s Sir Samuel Hoare, the UK’s “Ambassador on a Special Mission,” British embassy employee and covert spy Alan Hillgarth, and, most important of all, Juan Luis Beigbeder, first seen as High Commissioner of Spanish Morocco, then later as Franco’s Foreign Minister in Madrid.

The young dressmaker establishes contact with Beigbeder after an English woman, Rosalinda Powell Fox — also an historical figure — approaches her for a spectacular evening dress at very short notice. They quickly become friends, and eventually Rosalinda offers help in getting the seamstress’ mother out of Madrid and to the safely of Tetouan. The seamstress begins to attend official functions, but things get increasingly complex when it becomes clear that Beigbeder is less than wholly in sympathy with the ideas of the Fascists in whose state he’s functioning in increasingly important roles. After she has been recruited by Hillgarth to work as a British agent, stitching messages in Morse code into the hems of dresses, the couturier is then asked by Beigbeder to arrange for some documents of a dissident nature to be taken out of the country, secure in the UK’s diplomatic bag.

This first novel took Spain by storm and has reportedly sold more than a million copies there. This is of course not automatically a recommendation — I’m a traditional book reviewer, after all — but it does to some extent explain the nature of the product. With its evocation of the North African scene — sand, sun, goats, blue-and-white awnings fluttering in a sea breeze — and its knowledge of dressmaking, of silk braid and red satin, this is a congenial, untroubling tale. It’s also well researched, able to range from references to King Alfonso XIII of Spain to the Spanish banknotes of the time, with Columbus on the 100-peseta bill and Don John of Austria on the 500-peseta bill.

Even more importantly, the author appears to get the politics right. British policy of the era was to keep Spain out of the war. Beigbeder is in sympathy, telling Franco that Spain needed wheat and oil from Britain and the US, and that in addition he should do all he could to keep the Germans out of Spain’s domestic affairs. However, the British also wanted to use Madrid’s social scene to get as much information as they could about the mind-sets and plans of individual Germans living there. Discovering such information becomes the seamstress’ first task in espionage.

There are few grand reversals in the plot, the surprise revelations of past involvements and present betrayals that are the stuff of the spy novel. Instead, it proceeds at a leisurely pace, so much so that at one point I pondered on whether the author had used Balzac’s reputed method of writing a series of sentences and then expanding each of them into a paragraph. But this isn’t really a spy story at all, rather an imaginative re-creation of a past world with romantic, political, social and quietly personal elements carefully woven together. The virtues of an upmarket dressmaker, in other words, seem to inhabit the soul of this novelist as well.

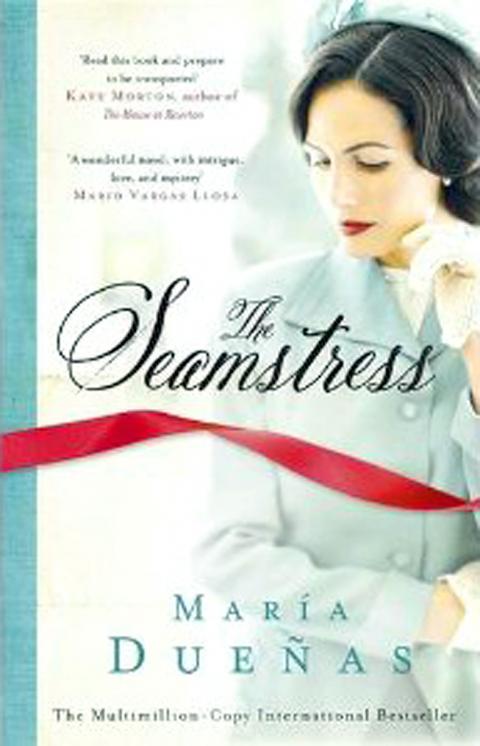

The English-language book trade needs a certain number of books of this type — novels that don’t demand a huge amount of intellectual agility on the part of the reader, but are at the same time professionally written and refuse the blockbuster’s stock in trade of gratuitous violence and graphic sex scenes. You don’t need to be a genius to enjoy The Seamstress, nor do you need to be a woman, though it will probably attract more female than male readers. Instead, it will fill up a good many empty hours. The translation by Daniel Hahn flows very smoothly, though I did have to wonder whether “inolvidable” was a leftover from the original Spanish.

Most of all, this isn’t a book stamped with any unmistakable mark of the author’s personality, at least in this English-language version. I know no more about Maria Duenas now I’ve finished the book than I did before I started it. Irony, comedy, scenes of heartbreaking tenderness or of nail-biting tension are all absent, as are purple passages. In conclusion, then, I wouldn’t go out of my way to press this novel on everyone I know, but nor would I argue strongly against it. However, Spain in the 1930s aroused intense passions all over Europe, and it’s when considering this that this novel begins to appear, for reasons that are hard to understand, surprisingly passionless.

Under pressure, President William Lai (賴清德) has enacted his first cabinet reshuffle. Whether it will be enough to staunch the bleeding remains to be seen. Cabinet members in the Executive Yuan almost always end up as sacrificial lambs, especially those appointed early in a president’s term. When presidents are under pressure, the cabinet is reshuffled. This is not unique to any party or president; this is the custom. This is the case in many democracies, especially parliamentary ones. In Taiwan, constitutionally the president presides over the heads of the five branches of government, each of which is confusingly translated as “president”

Sept. 1 to Sept. 7 In 1899, Kozaburo Hirai became the first documented Japanese to wed a Taiwanese under colonial rule. The soldier was partly motivated by the government’s policy of assimilating the Taiwanese population through intermarriage. While his friends and family disapproved and even mocked him, the marriage endured. By 1930, when his story appeared in Tales of Virtuous Deeds in Taiwan, Hirai had settled in his wife’s rural Changhua hometown, farming the land and integrating into local society. Similarly, Aiko Fujii, who married into the prominent Wufeng Lin Family (霧峰林家) in 1927, quickly learned Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) and

The low voter turnout for the referendum on Aug. 23 shows that many Taiwanese are apathetic about nuclear energy, but there are long-term energy stakes involved that the public needs to grasp Taiwan faces an energy trilemma: soaring AI-driven demand, pressure to cut carbon and reliance on fragile fuel imports. But the nuclear referendum on Aug. 23 showed how little this registered with voters, many of whom neither see the long game nor grasp the stakes. Volunteer referendum worker Vivian Chen (陳薇安) put it bluntly: “I’ve seen many people asking what they’re voting for when they arrive to vote. They cast their vote without even doing any research.” Imagine Taiwanese voters invited to a poker table. The bet looked simple — yes or no — yet most never showed. More than two-thirds of those

In the run-up to the referendum on re-opening Pingtung County’s Ma-anshan Nuclear Power Plant last month, the media inundated us with explainers. A favorite factoid of the international media, endlessly recycled, was that Taiwan has no energy reserves for a blockade, thus necessitating re-opening the nuclear plants. As presented by the Chinese-language CommonWealth Magazine, it runs: “According to the US Department of Commerce International Trade Administration, 97.73 percent of Taiwan’s energy is imported, and estimates are that Taiwan has only 11 days of reserves available in the event of a blockade.” This factoid is not an outright lie — that