Few of us had much clue what we would find as we drifted past a deserted border post into a country run for as long as I could remember by a man regarded as part monster, part clown. What would these newly liberated areas of Libya, under the shaky control of the fledgling revolutionary government, be like after 42 years in the grip of Muammar Gaddafi? Some of what we found as reporters was of little surprise. Accounts of life under tyranny ranged from bitter recollections of persecutions and public hangings of dissidents to the necessary demonstrations of acquiescence through conformities such as the requirement that all the shop shutters be painted green.

But it was also swiftly clear in the early days of the Libyan revolution that here was an uprising, and a people, in many ways different to what was shaking other parts of the Arab world. Having thrown off the yoke of fear, Libyans in Benghazi and other newly liberated areas seemed almost ashamed at having put up with the old dictator for so long. And so they set about to redeem themselves with a courage and determination they could scarcely believe they had found. There would be no compromise.

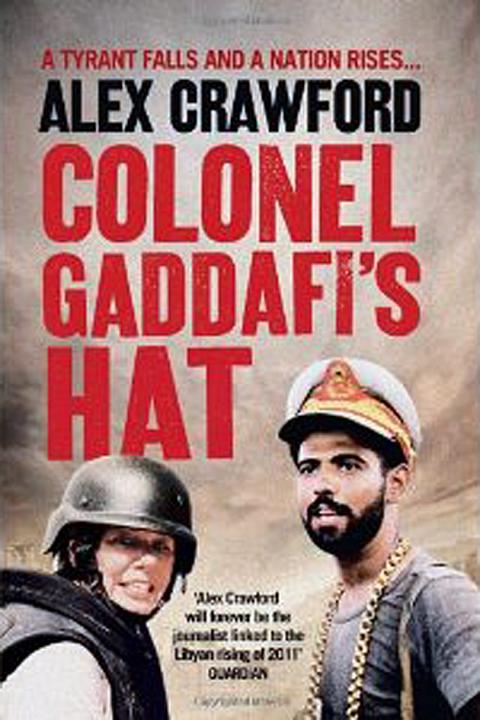

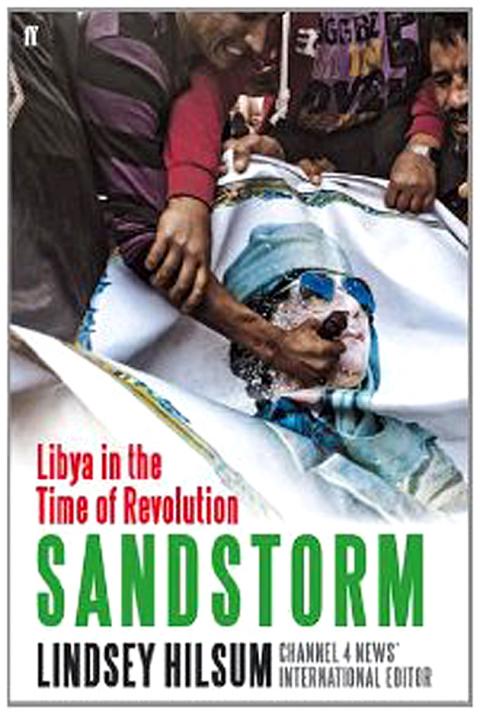

Two books by distinguished television correspondents — Lindsey Hilsum of the UK’s Channel 4 News and Alex Crawford of Sky News — capture the drama of those uncertain days, as popular revolution morphed into armed conflict. Hilsum, in her masterful account, draws on pre-revolutionary visits to Tripoli, where she encountered a fearful and sullen population, as well as her reporting of the uprising and more recent research to produce an account with historical depth to match dramatic reportage.

At the center of it all, of course, is Gaddafi. Hilsum captures the delusions of one of the last members of a breed — the president for life — that has largely disappeared from the rest of Africa, although the self-styled “Brother Leader” maintained he was merely guiding the people. He appears to have been sincerely baffled by the popularity of the uprising.

Sandstorm recounts life under Gaddafi through the moving and sometimes chilling accounts of his subjects. It’s a country where fans could only refer to football players by number, not name, in case one of them became more popular than the Brother Leader. The exception was one of the dictator’s brutal sons, Saadi, who fancied himself as a great midfielder and was appointed captain of the national squad. He also appeared — as a substitute — for an Italian club under, as Hilsum puts it, “a rare deal whereby the player pays the team.”

Saadi played his own part in the steady stream of resentments that saw Benghazi become the crucible of revolution. Alongside the horror of the public hangings of students at the city’s university, there was the less gruesome but deeply resented bulldozing of the local football club facilities by Saadi after fans paraded a donkey kitted out in a football shirt sporting his number.

Hilsum’s disgust shines through as she recounts how the west embraced Gaddafi. The man who armed the IRA and was blamed for the Lockerbie atrocity became so acceptable in European capitals for a time that the director of Britain’s MI6’s counter-terrorism division could call one of the dictator’s chief murderers and torturers “a friend.” In public, former British prime minister Tony Blair embraced Gaddafi. In private Britain delivered up the Brother Leader’s opponents for imprisonment and torture.

So what changed? For weeks, Libyans watched in awe as Tunisians kindled what became known as the Arab spring and then Egyptians declared Cairo’s Tahrir Square liberated territory. In Benghazi, they only dared hope that such a thing could happen in Libya. As it turned out, the fuse was lit by the arrest of a lawyer acting on behalf of relatives of political prisoners massacred by the military years earlier. (Hilsum captures the horror of their slaughter and the trauma of their families.)

That spark set off the most extensive revolution of the lot. While Egypt’s military continued to manipulate the democratic process and the new Tunisian leadership attempted to purge the new order of the old, Libya’s uprising morphed into civil war and a fitting end for Gaddafi, dragged from hiding in a drainpipe and shot without ceremony. Hilsum does not gloss over the darker side of the rebels. Racism resulted in the indiscriminate imprisonment and even murder of innocent workers from other parts of Africa falsely accused of being mercenaries. Those suspected of residual loyalty to Gaddafi have often fared little better.

In contrast to Hilsum, Crawford — whose admirable and brave coverage of Libya for Sky News included riding into Tripoli with rebels liberating the city — has written a breathless diary of reporting the uprising. In Colonel Gaddafi’s Hat she offers few of the historical insights of Sandstorm and the voices of Libyans don’t exactly shine through. But she does give a good account of the drama of those uncertain days when it was far from clear the revolution would be won. She also delves into what it is to be a reporter grappling with the frustration and anger that dogs journalists covering conflicts.

Crawford’s frustrations run so deep that when she gets home to her husband and children during a break from Libya, she tries to hunt down the best way to contact the foreign secretary, William Hague, and tell him to look at the Sky News pictures and do something. The West did do something: bomb. NATO’s role was controversial, although there’s no doubt that it saved the revolution in its early days, and that French and British training and weapons were important in delivering up the final victory. What the Libyans do with that remains to be seen, as both Hilsum and Crawford recognize.

Publication Notes

Colonel Gaddafi’s Hat

By Alex Crawford

304 pages

Collins

Hardcover: UK

Sandstorm

By Lindsey Hilsum

320 pages

Faber

Hardcover: UK

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) hatched a bold plan to charge forward and seize the initiative when he held a protest in front of the Taipei City Prosecutors’ Office. Though risky, because illegal, its success would help tackle at least six problems facing both himself and the KMT. What he did not see coming was Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (將萬安) tripping him up out of the gate. In spite of Chu being the most consequential and successful KMT chairman since the early 2010s — arguably saving the party from financial ruin and restoring its electoral viability —

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,