The Victorians were very interested in Norse mythology. It was a concern created in part by philology, which had, along with geology, an exceptional status at the time as an area of study that could throw light on mankind’s past. While fossils in rocks told stories about the distant history of life on Earth, philology could tell us about the history of mankind before the invention of writing. If languages could be shown to be related, then their speakers had obviously once had some sort of connection as well. It’s consequently not surprising that J.R.R. Tolkien, who used ancient Norse mythology to such great effect in his fiction, was also in his day the most highly esteemed Norse philologist in the English-speaking world.

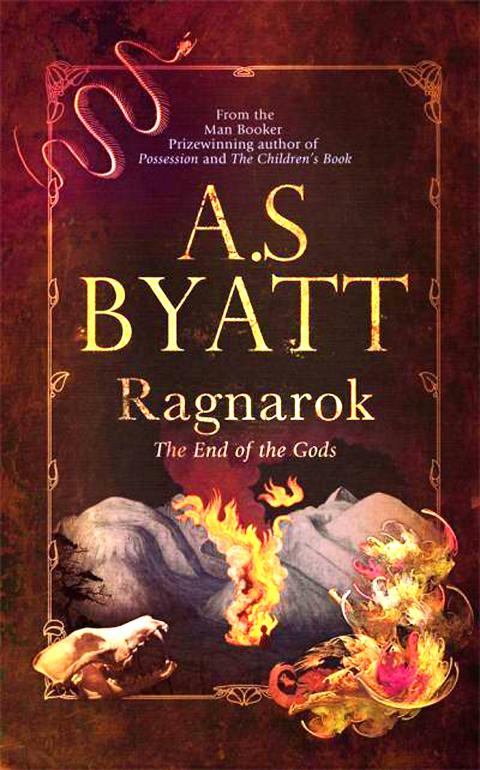

A.S. Byatt says she was asked to tell the story of one of her favorite myths for a series being published by Canongate. She chose the Norse story of Ragnarok, or “the twilight of the gods,” although she adds that experts tell us this is probably a mistranslation, and what was really meant was the final battle in which the gods would be defeated, and darkness and cold reign over the Earth.

Byatt tells the story with considerable flair, mixing ancient elements with her own memories of being a small girl (“the thin child”) evacuated from wartime Sheffield in the UK to the countryside. There she read an old German retelling of the stories, and felt close to everything they narrated

through her contact with the local rural landscape.

Her great set pieces are the descriptions of the tree at the center of the world, Yggdrasil, and its maritime equivalent, a monstrous bull-kelp called Randrasill. Later, in what constitutes the best part of the book, she retells the story of the death of Baldur, killed by his blind brother Hodur using a spear of mistletoe (the only wood that could harm him), his arm guided by the half-god Loki.

The Victorians’ interest in all this is displayed by Matthew Arnold’s poem Balder Dead (variations of spelling are normal in myths, as Byatt herself comments), and William Morris’ references to him in his many renderings of Icelandic material in both verse and prose. When Wagner used part of the story for his Ring cycle of operas, he was occupying an area that was already prominent in the cultural atmosphere of his times.

Today, Baldur’s Gate is a computer game, and it’s impossible not to feel that Byatt is in a sense reclaiming the story for literature, while hoping at the same time to attract the young to a written version of stories they’ll already be familiar with from their online games.

Byatt isn’t the first to notice that the Norse gods were not over-endowed with intelligence, brutally killing on all sides and given to a rough-and-ready sense of humor. It’s probable the originators of these stories saw Nature itself as being like that, and the young version of A.S. Byatt in Ragnarok certainly sees things that way, instinctively taking to these old legends as reflecting the natural northern English world around her. Early on, she tells us, she rejected the “gentle Jesus” form of Christianity she witnessed in the local churches, quickly perceiving it as being a myth just like all the others, merely a less attractive one.

Despite the author’s insistence that her story isn’t an allegory and doesn’t have a moral, ecological doom dominates the last few pages. “Almost all the scientists I know,” she writes, “think

we are bringing about our

own extinction.”

The language of this book is frequently lush and evocative. “Odin” (ie, Wotan) “was the god of the Wild Hunt,” Byatt writes. “Or the Raging Host. They rode through the skies, horses and hounds, hunters and spectral armed men. They never tired and never halted; the horns howled in the wind, the hooves beat, they swirled in dangerous wheeling flocks like monstrous starlings.” Or this: “The Sea-Tree stood in a world of other sea-growth, from the vast tracts of bladderwrack to the sea-tangles, tangleweeds, oarweeds, seagirdles, horsetail kelps, devil’s aprons and mermaid’s wineglasses.”

Nevertheless, A.S. Byatt is as much a critic as she is an imaginative artist. “The thin child had a literal, visual imagination,” she writes here. There are places in this book where you can’t help wishing it was being written by the late Ted Hughes. He worked hard on his superb Tales From Ovid (2002) as he lay dying, and wouldn’t have introduced sentences pointing out that his other prose works also contained myths, as Byatt does. His verbs would have been stronger, and he’d have had less recourse to lists.

This is nonetheless an attractive book in several ways. It’s not a masterpiece of any kind, but it has its moments. Most importantly, you can’t help thinking that much of the writing is an epitaph for a beautiful planet that’s fast becoming irretrievably lost. The mythic gorgeousness may feel rather forced in places, but the concern for the vanishing natural world is real enough.

A short bibliography at the end contains titles such as The Killing of the Countryside, The Empty Ocean and Our Final Hour. It’s partly a tribute to Byatt’s book that I felt I wanted to get hold of them as soon as possible.

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the