When Fred Wilson, a prominent New York venture capitalist who has backed Twitter and Zynga, wanted to watch the New York Knicks game last month, he got an unpleasant surprise. Time Warner Cable was not showing the game because of a contract dispute.

Frustrated, he turned to the Internet for help. Within minutes he was streaming the game illegally on his big-screen TV.

“It’s not that we don’t want to pay for our sports entertainment,” Wilson wrote on his blog after the fact. “But last night we were turned into ‘pirates,’ as the entertainment industry likes to call us.”

Photo: EPA

Plenty of Knicks fans can sympathize with Wilson’s plight. And his rationale makes perfect sense to people in tech circles, who increasingly expect to have most everything available on demand, and resent it when media companies stand in their way.

That is not how media companies and the entertainment industry see it. From their perspective, tapping into pirate streams and file-sharing sites is no different from shoplifting in the supermarket.

“Copyright violations are a serious business and we don’t condone that in any way,” said Alexander Dudley, a Time Warner Cable spokesman, when asked about Wilson’s desperate measures.

Photo: AFP

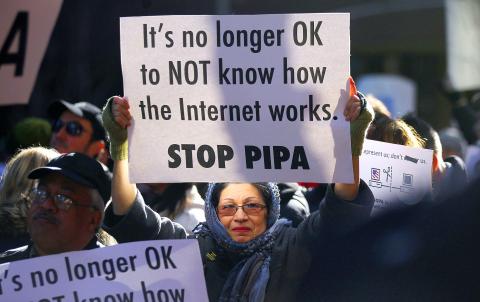

The recent highly publicized fight over the Stop Online Piracy Act, a bill put before the US House of Representatives and its counterpart in the Senate, the Protect Intellectual Property Act, threw a spotlight on this same disconnect between the Internet industry and the media giants of Hollywood and New York. Despite full-court lobbying by big players like the Motion Picture Association of America, lawmakers abandoned the bills after tech companies and groups, along with ordinary Internet users, mounted a frenzy of protests, saying the bills would hurt Internet freedom and innovation.

Now the challenge is for the two sides to find common ground on how to combat the piracy problem — though they can’t even come to terms on how big a problem it is.

“The fundamental issue is whether or not the sky is falling and the entertainment industry is being decimated by technology,” said James Berger, a lawyer who specializes in intellectual property and entertainment content licensing.

Seeking out an illicit stream of a game that you should be able to watch legitimately is one thing. But media companies say they are facing a relentless barrage of far less defensible thefts involving movies, television shows and music.

In a letter in December announcing its support for stronger anti-piracy legislation, the motion picture association said that “US$58 billion is lost to the US economy annually due to content theft, including more than 373,000 lost American jobs, US$16 billion in lost employees’ earnings, plus US$3 billion in badly needed federal, state and local governments’ tax revenue.”

A spokesman for the association, Howard Gantman, said the US$58 billion figure came from an economic model that estimated piracy’s impact on a range of tangentially related industries — florists, restaurants, trucking companies and so on.

Many outside the industry are skeptical of its analysis. “The movie business is fond of throwing out numbers about how many millions of [US] dollars are at risk and how many thousands of jobs are lost,” said Art Brodsky, who works for Public Knowledge, a digital rights group. “We don’t think it correlates to the state of the industry.”

In one of the most public steps forward since last month’s fight, Brodsky’s group pulled together a coalition of more than 70 tech companies and advocacy groups, including Amnesty International, Consumers Union, Reddit and the Electronic Frontier Foundation, that sent a letter to Congress on Monday calling for lawmakers to rethink their approach.

“Now is the time for Congress to take a breath, step back, and approach the issues from a fresh perspective,” the letter says. It urges Congress to quantify the extent of piracy and its economic effects “from accurate and unbiased sources, and weigh them against the economic and social costs of new copyright legislation.”

Some in the Internet world, including Tim O’Reilly, a noted investor and chief executive of the tech-books publisher O’Reilly Media, go so far as to question whether illegitimate downloading and sharing is such a bad thing. In fact, some say that it could even be a boon to artists and other creators.

“The losses due to piracy are far outweighed by the benefits of the free flow of information, which makes the world richer, and develops new markets for legitimate content,” he wrote in a blog post. “Most of the people who are downloading unauthorized copies of O’Reilly books would never have paid us for them anyway.”

That free flow of information, media companies worry, is making consumers accustomed to getting something for nothing. Privately, several senior media executives said technology companies wanted to devalue copyrighted media content because it ultimately benefited the technology companies’ business.

“If intellectual property developed by creative people and covered by copyright was as respected as intellectual property developed by engineers and protected by patents, this problem would greatly improve,” said a Viacom executive who was not authorized to discuss the matter publicly.

Viacom is currently appealing a copyright infringement case against YouTube. In 2010 a federal judge ruled in favor of YouTube’s owner, Google, which Viacom accused of seeking to profit from thousands of copyrighted clips from shows like The Daily Show With Jon Stewart that users had posted on YouTube.

Media executives have a particular beef with Google. Some claim it initiated the online fervor over the anti-piracy legislation in part to advance its own business interests. Michael O’Leary, a senior executive vice president at the motion picture association, put it this way: “I’d ask Google, ‘How many jobs do we have to lose before they start taking this seriously?”’

A Google spokeswoman, Samantha Smith, said the company was “heavily invested in the fight against piracy,” noting that last year it took down 5 million infringing Web pages and spent more than US$60 million to root out “bad ads,” including those for illegal or pirated goods.

Google also says it has developed ways to address the piracy problem on its own sites, pointing to Content ID, a system put in place after the Viacom suit was filed that helps copyright holders identify material they own on YouTube and decide whether to remove it or leave it up and share in the ad revenue.

Media companies have no plans to immediately revisit the anti-piracy legislation. Instead, several entertainment executives said they planned to reorganize and talk to labor unions, pharmaceutical companies and other backers of the legislation about a unified message so the anti-piracy and anti-counterfeiting movement was not just associated with Hollywood.

These executives, speaking on the condition of anonymity because the issue is so heated, also said they wanted to look at how they could better harness the Web to educate the public about piracy, something they admitted they failed to do last month.

Of course, as consumers embrace online video and music in both legal and illegal forms, media companies have also been learning new tricks. Warner Brothers, for example, now offers a digital locker, part of an industrywide push to Internet-based movie storage that allows customers who buy a DVD or Blu-ray disc to access the same movie on many different devices.

“We’re trying to create a compelling option for consumers, but at the end of the day, unlike the pirates, we’re charging them,” said Kevin Tsujihara, the president of home entertainment for Warner Brothers.

The digital locker is the latest effort to stem the decline in home entertainment revenue, driven largely by Netflix and Redbox rentals, but also by piracy. The research firm SNL Kagan estimates that industry revenue from video rentals and sales fell 10.5 percent to US$18.5 billion in 2010 from the year before.

Piracy has put the impetus on media companies to more quickly strike deals to make television and movies available on the Web legitimately. In 2007, Erik Flannigan, now the executive vice president of digital media at Viacom Entertainment Group, pulled up the Google search page on a giant screen at Viacom’s Times Square headquarters. He typed in South Park and took senior executives on a tour of Web sites offering pirated episodes.

Today, Comedy Central makes every episode of South Park, The Daily Show and The Colbert Report available free online. The efforts, Flannigan said, put a big dent in piracy. As for the television industry as a whole, Flannigan said: “You might not like the windows, or that shows go up and come down, but it’s a far cry from where we were.”

Still, Comedy Central shows do not make billions in syndication or in DVD sales like some TV series. The industry has been reluctant to make available shows like CBS’ The Big Bang Theory, which sold for US$2 million an episode to Time Warner’s TBS and Fox. That makes piracy a tempting option.

“If they don’t make content available where consumers are, they’re just shooting themselves in the foot,” said Ron Conway, a Silicon Valley investor and the head of the SV Angel investment fund.

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the