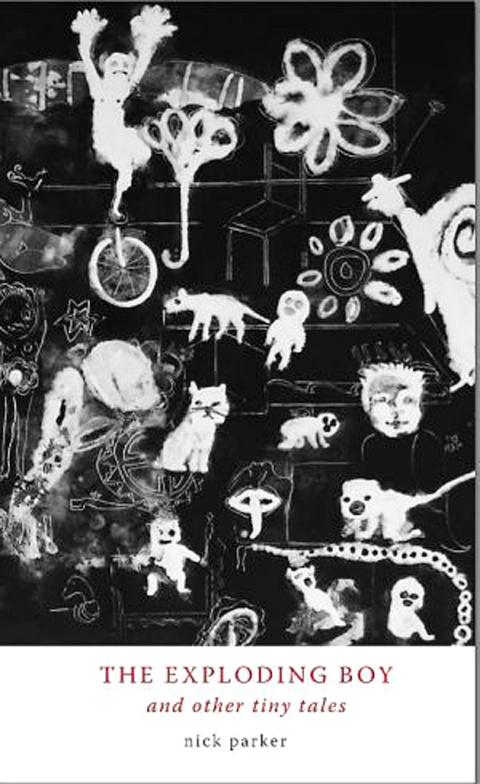

This is not what’s supposed to happen. This is what’s supposed to happen: a writer gets an agent, who then sells the writer’s book to a publisher, who kindly publishes the book, and distributes it to bookshops, and attempts to get it reviewed in newspapers. Nick Parker either didn’t know this, didn’t care, or tried it and it didn’t work. Instead, he has self-published his book of short stories, which he is selling through his own Web site, and as a Kindle ebook. He sent me a copy in the post. Lots of people send me self-published books. The Exploding Boy and Other Tiny Tales is the first time an author has sent me a self-published book that’s actually any good.

There are, of course, precedents. Self-publishing and DIY authors include, famously, William Blake, Lord Byron, Proust, Shelley, Ezra Pound, Walt Whitman, Gertrude Stein and Virginia Woolf. But the world of self-publishing is mostly inhabited by cranks and hucksters (though Blake, Byron, Whitman and Woolf could probably all be described as cranks, and Pound was a crank and a huckster). Things may be changing with the new rash of high-profile self-published novelists (Brunonia Barry and Amanda Hocking to name but two), but recent success stories still tend to be one of three kinds: the self-fulfilling I Made a Million Selling Kindle Ebooks and So Can You! ebook; the self-help book touted round personally by a conference-suite speaker (Jack Canfield’s Chicken Soup for the Soul); and the new age/conspiracy/weirder-than-weird novel (James Redfield’s The Celestine Prophecy). On the ever-widening self-publishing scale that goes all the way from botanically dyed, hand-colored avant-garde pamphlet at one end to the mobile-device-friendly, app at the other, The Exploding Boy and Other Tiny Tales is most definitely at the avant-garde end.

But not in a pretentious, poppycock way: what we get are 42 short, swift, crowd-pleasing stories. The great, odd American short story writer George Saunders has an essay, The Perfect Gerbil, in his book The Braindead Megaphone about the even greater, even odder American short story writer Donald Barthelme, which explains that part of the appeal of Barthelme’s work “involves the simple pleasure of watching someone be audacious.” Saunders claims that “the real work” of a story “is to give the reader a series of pleasure-bursts.”

The Exploding Boy is full of little pleasure-bursts. The first story, the exploding boy (all titles are in lower case, alas, one of the book’s more irritating mannerisms), begins: “We only call him the Exploding Boy now, of course; retrospectively.” Device safely planted, the second sentence goes off, as it must, like this: “For most of last year he was known only as Ticking Boy.”

“We are in need of a new type of fire,” another story begins, a statement that requires some sort of explanation. We are given first a list: “We admit that the fires that we already have are all perfectly good fires: the fires for burning logs for warmth; the fires for lighting cigarettes; the fires for burning books with.” And then an explanation: “We need a fire for the new digital age. A fire that is streamable, downloadable, scalable, printable, storable in hard drives, retrievable and searchable.” The story fragments from the history of pest control begins: “This is how we keep the rabbits under control. At night, when they are asleep in their hutches and holes, we creep out and ... whisper to them.”

One man’s daring audacity, of course, is another’s self-indulgent whimsy, and if a story called, for example, the field of ladders, which begins “We went to see the field of ladders,” is going to cause you annoyance, then you should probably avoid this. Some of the stories come close to prose poems. Indeed, knots familiar to donald crowhurst appears to be an actual prose poem: “Running knots. / Bowline knots. / Miller’s knots. / Stopper knots. / Stomach knots.” One can perhaps forgive the occasional prose poem, particularly if it’s found among other stories that are thought experiments (the summer of the pakflake), straight autobiography (found report no 1: keith jarrett plays a concert) and dialogues (why the national anthem is rubbish).

The Exploding Boy flies in the face — or flies into the face, like literary shrapnel — of received wisdom. First, it proves that self-publishing can be more than a private pleasure. And second, that the short story remains a public good. Impertinent. Unlikely. And astonishing.

On the Net: theexplodingboy.com

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 28 to May 4 During the Japanese colonial era, a city’s “first” high school typically served Japanese students, while Taiwanese attended the “second” high school. Only in Taichung was this reversed. That’s because when Taichung First High School opened its doors on May 1, 1915 to serve Taiwanese students who were previously barred from secondary education, it was the only high school in town. Former principal Hideo Azukisawa threatened to quit when the government in 1922 attempted to transfer the “first” designation to a new local high school for Japanese students, leading to this unusual situation. Prior to the Taichung First

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) hatched a bold plan to charge forward and seize the initiative when he held a protest in front of the Taipei City Prosecutors’ Office. Though risky, because illegal, its success would help tackle at least six problems facing both himself and the KMT. What he did not see coming was Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (將萬安) tripping him up out of the gate. In spite of Chu being the most consequential and successful KMT chairman since the early 2010s — arguably saving the party from financial ruin and restoring its electoral viability —

The Ministry of Education last month proposed a nationwide ban on mobile devices in schools, aiming to curb concerns over student phone addiction. Under the revised regulation, which will take effect in August, teachers and schools will be required to collect mobile devices — including phones, laptops and wearables devices — for safekeeping during school hours, unless they are being used for educational purposes. For Chang Fong-ching (張鳳琴), the ban will have a positive impact. “It’s a good move,” says the professor in the department of