Why are the 1950s so hard to come to terms with?

In one sense they represent an era of slightly spurious good times, an island of peace and prosperity after the horrors and deprivations of World War II. It wasn’t that things were really that good, you feel, but rather that there was an irresistible compulsion on the part of people living then, in both Europe and the US, to persuade themselves that they were. Hence it appears as a sort of placid haven, conservative in taste as in politics, managing to hold its own between the grimness of the 1940s and the radical innovations of the 1960s. But “appears” is the key word.

It’s most prominent statesmen were conservatives — Eisenhower, De Gaulle, Macmillan, all three with the power to unleash nuclear weapons. Boys had polished shoes, short hair and side partings. Frank Sinatra was a key voice on the airwaves (TV was in its infancy, and often only in black-and-white), and even well-established modernists such as Picasso were still greeted with a shudder. The pre-war decades had in many respects been more radical, but this was a time when the middle classes reigned. After being allowed a mere sliver of cheese every week under the UK’s food rationing system, to inhabit a suburban home of your own, with its clipped lawn and cheerful flower beds, was easily seen as a form of paradise.

These days we tend to be more interested in the era’s rebels — Elvis Presley, James Dean, the Beat Generation — all precursors of what was to come. But the decade also produced its own characteristic art that, by and large, has worn well — books by Graham Greene and Lawrence Durrell, films by Bergman and Fellini, and some sumptuous classical recordings.

The future wasn’t only present in the person of rebels — the rich and successful were also forging ahead into new lifestyles. One of the most significant of these was international air travel. The major airlines were getting into their stride, and the new jets were in the process of revolutionizing travel.

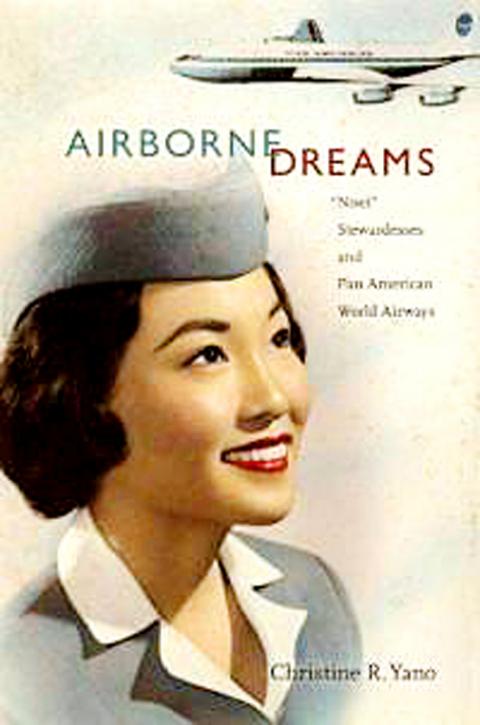

Christine R. Yano’s Airborne Dreams focuses on Pan Am, or Pan American World Airways. It’s a paradoxical area because this new technology, rightly seen as era-defining and inaugurating “the jet age” with its characteristic “jet-setters,” was still intensely conservative in its ethos. One example is its employment policy with regard to stewardesses. Once the presence of non-whites was accepted into the concept, stewardesses were employed on a racial quota basis, something that is hard to swallow today.

The book looks at the stewardesses of Japanese ethnic origin, first introduced in 1955. Pan Am felt that it was desirable to have Japanese-speaking personnel on board, not only to cater to its Japanese passengers on long-haul flights (divided in those days into many short stages), but also to confirm the “exotic” nature of long-distance air travel. The well-heeled passengers were encouraged to feel cosmopolitan and, as if to confirm the effect, they were given some exotic-looking stewardesses to cater to their in-flight needs.

These were often second-generation Japanese immigrants to the US. But it wasn’t so long since America had been at war with Japan, and US citizens of Japanese descent had been interned. So some women who could remember being in American internment camps suddenly found themselves at the forefront of the modern age, and in effect representing their nation on its most prestigious airline.

And Pan Am was prestigious. Its founder and head from 1927 to 1968, Juan Trippe, would have liked it to have been the US national airline, even its sole international carrier. But Washington opted instead for a policy of free competition and, unlike many other countries, the US never had a flagship national carrier. Even so, Pan Am was a first among equals, with close contacts to the government and happily engaging in “confidential” missions. To the flying public, its style was both luxurious and formal, in contrast to (according to this author) the friendly informality of United.

The former stewardesses of Japanese background interviewed in this book don’t have anything very thrilling to say. They were on the whole conventional people, and probably believed that they had to remain so if they wanted to keep their jobs. Any popular idea that they were sex symbols, geishas of the sky, apparently wasn’t reciprocated in practice. Air stewardess may have a “coffee, tea or me” reputation (to quote a phrase Yano uses), but on Pan Am it was different, or so this book asserts.

Parents’ reactions to their daughters taking such work varied. The more affluent claimed to feel ashamed that they hadn’t opted to be, say, teachers, and were only mollified when they discovered that stewardesses weren’t given tips.

Grim times awaited Pan Am, however. It was involved in the worst disaster in aviation history in Tenerife in 1977, and was the victim of the notorious terrorist bombing over Lockerbie, Scotland in 1988. The airline declared itself bankrupt in 1991.

Yano appears anxious to reflect the glamour of Pan Am and its Japanese-descended stewardesses in their heyday while feeling obliged to incorporate the fashionable academic perspectives of race and class as well. The result is a slightly incongruous work, with the occasional insight but many wearying pages. The author is now working on a book about Hello Kitty.

You can’t help wondering whether any of these stewardesses thought about the fact that many of the planes they were working on had been built in the same factories as those that rained fire and radiation on their ancestral homeland. Probably not. The 1950s, after all, was an age when many of the truths we take for granted today were left discreetly unmentioned.

May 26 to June 1 When the Qing Dynasty first took control over many parts of Taiwan in 1684, it roughly continued the Kingdom of Tungning’s administrative borders (see below), setting up one prefecture and three counties. The actual area of control covered today’s Chiayi, Tainan and Kaohsiung. The administrative center was in Taiwan Prefecture, in today’s Tainan. But as Han settlement expanded and due to rebellions and other international incidents, the administrative units became more complex. By the time Taiwan became a province of the Qing in 1887, there were three prefectures, eleven counties, three subprefectures and one directly-administered prefecture, with

It’s an enormous dome of colorful glass, something between the Sistine Chapel and a Marc Chagall fresco. And yet, it’s just a subway station. Formosa Boulevard is the heart of Kaohsiung’s mass transit system. In metro terms, it’s modest: the only transfer station in a network with just two lines. But it’s a landmark nonetheless: a civic space that serves as much more than a point of transit. On a hot Sunday, the corridors and vast halls are filled with a market selling everything from second-hand clothes to toys and house decorations. It’s just one of the many events the station hosts,

Two moves show Taichung Mayor Lu Shiow-yen (盧秀燕) is gunning for Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) party chair and the 2028 presidential election. Technically, these are not yet “officially” official, but by the rules of Taiwan politics, she is now on the dance floor. Earlier this month Lu confirmed in an interview in Japan’s Nikkei that she was considering running for KMT chair. This is not new news, but according to reports from her camp she previously was still considering the case for and against running. By choosing a respected, international news outlet, she declared it to the world. While the outside world

Through art and storytelling, La Benida Hui empowers children to become environmental heroes, using everything from SpongeBob to microorganisms to reimagine their relationship with nature. “I tell the students that they have superpowers. It needs to be emphasized that their choices can make a difference,” says Hui, an environmental artist and education specialist. For her second year as Badou Elementary’s artist in residence, Hui leads creative lessons on environmental protection, where students reflect on their relationship with nature and transform beach waste into artworks. Standing in lush green hills overlooking the ocean with land extending into the intertidal zone, the school in Keelung