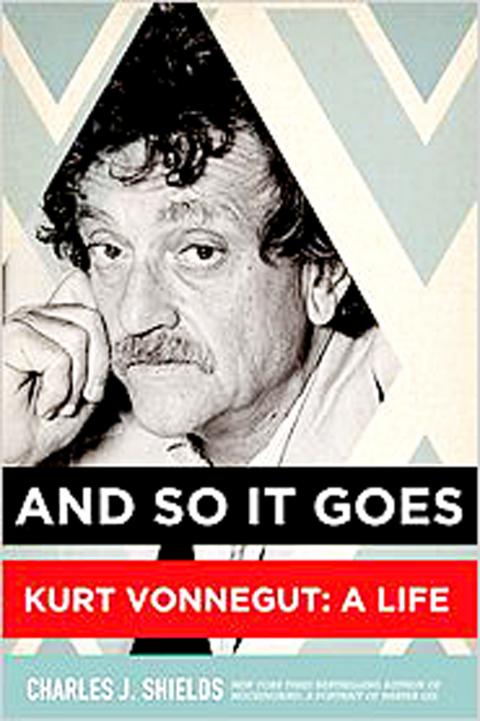

Charles J. Shields got nowhere with Harper Lee when he tried to interview her for the 2006 biography Mockingbird. But he got lucky with Kurt Vonnegut. Shields found a lonely talkative octogenarian who had scores to settle and a reputation that badly needed restoring. Vonnegut had once told Martin Amis that the only way he could regain credit for his early work, those books from the 1950s and 1960s once so beloved by college kids, would be to die. He died April 11, 2007, less than a year after Shields first approached him. And the two did not spend much time together. But Vonnegut gave the go-ahead that has allowed Shields to construct And So It Goes, an incisive, gossipy page-turner of a biography, even if it’s hard to tell just how authorized this book really is. Denied permission to quote from Vonnegut’s letters, Shields relies on paraphrases and patchwork to create a seamless-sounding account. Astonishingly, this book has nearly 1,900 notes to identify separate sources and quotations. But it doesn’t sound choppy at all.

Although he does not acknowledge it, Shields shares the slick commercial instincts that shaped Vonnegut’s early career. He has written about Central America, sexual disorders, test taking, Saddam Hussein, Martha Stewart and Buffalo Bill Cody in books never meant for the mainstream. Vonnegut began his career with journalism, writing public relations copy and paperbacks that were sold in drugstores. He was married, in his mid-40s and a father of three, teaching at the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop by the time he became an overnight sensation.

Shields is not shy about using the words “a definitive biography of an extraordinary man” to describe his book. And So It Goes is quick to trumpet its biggest selling points. Shields means to separate image from perception: He depicts Vonnegut as an essentially conservative Midwesterner, proud of his German heritage and capitalist instincts, who developed an aura of radical chic. He also describes a World War II isolationist who aligned himself with Charles Lindbergh yet became an antiwar literary hero. And he finds a life-affirming humanist sensibility in a writer celebrated for black humor.

And So It Goes also traces the paradoxes in Vonnegut’s personal life. He was widely regarded as a lovable patriarch, for instance, at a time when he had left his large family behind. He sustained a populist reputation even when he developed a high social profile in New York with photographer Jill Krementz, his second wife. Krementz clearly did not cooperate with Shields. The book takes frequent whacks at her, holding her accountable for much of the unhappiness in Vonnegut’s last years.

Shields provides a good assessment of misconceptions about Vonnegut’s writing. Those impressions persisted throughout his later life, perhaps because the books that followed Cat’s Cradle, The Sirens of Titan, God Bless You, Mr Rosewater and Slaughterhouse-Five became increasingly unreadable.

“On the strength of Vonnegut’s reputation, Breakfast of Champions spent a year on the best-seller lists,” Shields writes of that disappointment, “proving that he could indeed publish anything and make money.”

Vonnegut and his first wife, Jane, raised three orphaned nephews as well as their own three children, in a cacophonous house on Cape Cod. “There was a definite disconnect,” one of them says, between his whimsical writerly sweetness (one critic labeled him “an ideal writer for the semiliterate young”) and irascible manner. And for the first part of his writing career Vonnegut successfully compartmentalized his familial and writerly personas. Eventually they began to blend, as Vonnegut made himself more of an explicit persona in his writing. Once the real experiences and opinions took over, allowing him to trade on his celebrity, he became a target of vituperative attack.

“This is a speech I’ve given a hundred times, but I do it to make money,” Vonnegut told an audience in the days when his charm began to wane. And So It Goes depicts him as living in his “own private rain,” stuck in a “hexed” second marriage, nursing grudges and running out of writerly inspiration. When he accepted a fellowship at Smith College in the fall of 2000, the student newspaper complained bitterly: “Deify Celebs Much, Smith?” And So It Goes isn’t a book to rekindle the popularity of its subject’s work. But it offers a potent account of struggle, popularity and painful longevity, which extended to the point where Vonnegut could toss off little bits of “news from nowhere” and not much else. Twitter might have suited him perfectly if he were still here.

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the