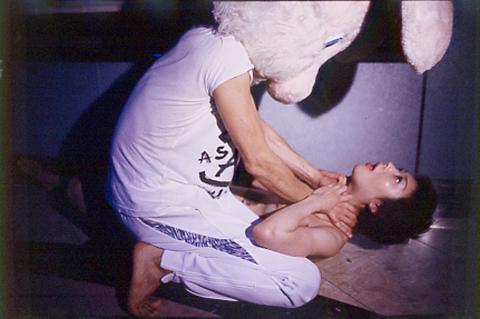

Takahisa Zeze made his name shooting films on the streets and at friends’ homes with a tiny crew of four. The team usually made hour-long movies in four to six days on a limited budget of US$44,000. Heavy on nudity and sex, the films featured grisly murders, incest, existential musings and cryptic characters that included Death in a pink bunny suit.

These movies are part of a genre called “pink films,” a type of sexploitation cinema unique to Japan. Zeze has been lauded as one of the genre’s most innovative and distinctive auteurs since he made his debut in the pink field in 1989.

He’s come a long way since then. Heaven’s Story is the director’s latest work, a 278-minute magnum opus on crime and punishment. The epic film won the International Critics Prize (FIPRESCI) and the Network for the Promotion of Asian Cinema (NETPAC) Award at last year’s Berlin Film Festival.

Illustration: Blake Carter, Taipei Times

Photo courtesy of Taipei Film Festival

“The boundary between pink films and regular movies should be done away with,” Zeze told the Taipei Times while in town to attend the Taipei Film Festival (台北電影節) a couple of weeks ago. “Boundaries are everywhere in our world: black people and white people, the rich and the poor. We [the “Four Heavenly Kings of Pink,” as Zeze and three of his colleagues have been dubbed] are not activists, but our desire to eradicate the boundary is the same.”

Having first appeared in the early 1960s, pink films differ greatly from the Western notion of pornographic movies. While they are of an erotic nature, they do not contain explicit depictions of genitalia or hardcore sexual intercourse, both of which are prohibited by Japanese censorship laws. The movies are independently produced by small production companies for a network of specialist cinemas. This specific mode of production and exhibition circumstances are regarded as the defining feature of the genre by Jasper Sharp, a British expert on the subject and the author of Behind the Pink Curtain: The Complete History of Japanese Sex Cinema.

To Zeze, the beauty of pink cinema is the freedom it promises: Filmmakers can do whatever they like with the projects as along as they deliver four sex scenes in the hour-long running time. When he first got started, the director recalled, pink films were made mostly by young filmmakers eager to experiment, and ran a wide gamut of styles including experimental, narrative-driven, comedies and others that are solely for the purpose of providing titillation.

Photo courtesy of Taipei Film Festival

“Old men watch them for pornographic content,” the 51-year-old director said. “Young people come for the sake of art. The audience is mixed. To me, it is a very powerful thing.”

Pink cinema came to be seen as an important medium for fledgling talents. Many of today’s top directors, such as Masayuki Suo and Yojiro Takita, got their starts in the clandestine industry. As for Zeze, he came into prominence along with fellow directors Kazuhiro Sano, Toshiki Sato and Hisayasu Sato in the late 1980s. Collectively known as the Pinku Shitenno, or the “Four Heavenly Kings of Pink,” quartet stood out from the crowd with highly individual works that reflect their artistic pursuits and social concerns. However, being less overtly sexual and more thought-provoking means that their films needed a new, wider audience outside the traditionally ojisan — or older men — theater circuit.

“Our films were considered difficult,” Zeze said. “Ojisan hated them. Only young people watched them. We were almost out of work. Then our movies were invited to the Rotterdam Film Festival [in 1995].”

Photo courtesy of Taipei Film Festival

Films by the Pinku Shitenno quickly generated international interests. Meanwhile in Japan, art-house theaters began to showcase their works and refer to them as the avant-garde of pink films. Zeze says that in important part of his work is challenging the stigma associated with the genre.

“Back then, pink films were considered the lowest,” he said. “People thought they were bad and it was perfectly okay if they disappeared. So we all shared a common thought of showing that we were not unimportant and it was not okay if we disappeared.”

Zeze turned to mainstream cinema in 1997 with Kokkuri, a teen horror film that revolves around a spirit conjured up using a Ouija board.

Photo courtesy of Taipei Film Festival

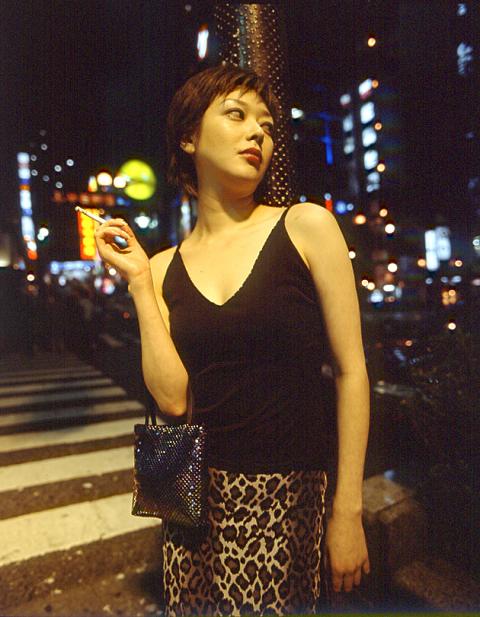

Unlike many of his colleagues who used pink filmmaking as a springboard for more mainstream productions, Zeze periodically goes back to his roots in pink, alternating conventional genre flicks such as the action comedy Rush! (2000) and romantic fantasy Dog Star (2002) with softcore porn productions including Dirty Maria (1998) and Tokyo X Erotica (2001).

Pink or non-pink, Zeze’s cinematic world is often inspired by real-life crimes and perpetually inhabited by murderers, mavericks and outcasts. In Heaven’s Story, victims and perpetrators of senseless violence embark on existential quests in a circle of revenge, survival, atonement and rebirth. In Crevice of Skin (2004), a withdrawn young man kills his mother and escapes into the countryside with his autistic aunt, with whom he has an incestuous relationship. Dirty Mania sees a murderess lure the husband of the woman she killed into desperate sex in a snowbound wildness.

“People who live happily in the society don’t interest me,” the director said. “I am drawn to those who try to escape. People who are inside cannot see what happens around them, but the outcasts can see more clearly from the outside. I am interested in crimes. Through my films, I want to prove that humanity is inherently good. People are complicated. I want to show what happens to them before and after they commit crimes.”

Photo courtesy of Taipei Film Festival

Both Dirty Maria and Crevice of Skin are representative of Zeze’s brooding, atmospheric erotic works that explore the dark side of humanity. Dialogue is kept to a bare minimum and the apathetic characters’ motives are never fully explained. Motifs of savageness and death are pervasive and the grim, depressing ambience is enhanced by mood-drenched cinematography and the scarcity of background music. Zeze’s approach to the movies is cold and detached. His films easily transcend their pink origins and stand out as provocative mediations on challenging subjects that irk casual viewers merely looking for pornographic pleasure.

The director also uses cinema to seek answers to his questions about the world and society. The most pronounced example is Tokyo X Erotica, which weaves together a number of different characters and time periods to build a surreal, kinky reflection on Japanese society. Spanning from 1982 to 2002, the nonlinear story opens with one character killed in the Aum Shinrikyo gas attacks of 1995. News of the massacre in Tiananmen Square and the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 are broadcast on flickering televisions and over the radio. Against a backdrop of economic slump and social crisis, men and women continue to indulge in orgies of perverted sex and adultery.

“The subject of pink films is sexuality,” Zeze said. “It is a constant, but time changes. How will people’s sexuality and small stories reflect the times they live in? How will we survive the times? I always think about these questions.”

Much to his pink film fans’ disappointment, Zeze said recently that he will stop making softcore porn, but not because he has now made a name for himself in the mainstream field. “The pink industry has been in decline. I am old, and I should not take opportunities away from young filmmakers.” But he added: “I will definitely make pink again if the industry gets better.”

For Zeze, there is no distinction in making an erotic film or mainstream cinema. But does he draw a distinction between art and pornography?

“Some people think art is boring, while others find it entertaining. Like art, pornography is a subjective thing. One is not superior to the other, and the boundary between the two should not exist,” Zeze said, citing director Nagisa Oshima’s In the Realm of the Senses. “Oshima was prosecuted on obscenity charges because of the film. He went to court and asked, ‘Why is being obscene a crime?’”

The Taipei Film Festival is holding marathon screenings of Zeze’s Tokyo X Erotica, Dog Star and Heaven’s Story today at Taipei Zhongshan Hall (台北市中山堂), 98 Yanping S Rd, Taipei City (台北市延平南路98號), starting at 11am. For more information, visit the festival’s Web site at www.taipeiff.org.tw.

June 2 to June 8 Taiwan’s woodcutters believe that if they see even one speck of red in their cooked rice, no matter how small, an accident is going to happen. Peng Chin-tian (彭錦田) swears that this has proven to be true at every stop during his decades-long career in the logging industry. Along with mining, timber harvesting was once considered the most dangerous profession in Taiwan. Not only were mishaps common during all stages of processing, it was difficult to transport the injured to get medical treatment. Many died during the arduous journey. Peng recounts some of his accidents in

“Why does Taiwan identity decline?”a group of researchers lead by University of Nevada political scientist Austin Wang (王宏恩) asked in a recent paper. After all, it is not difficult to explain the rise in Taiwanese identity after the early 1990s. But no model predicted its decline during the 2016-2018 period, they say. After testing various alternative explanations, Wang et al argue that the fall-off in Taiwanese identity during that period is related to voter hedging based on the performance of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Since the DPP is perceived as the guardian of Taiwan identity, when it performs well,

The Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) on May 18 held a rally in Taichung to mark the anniversary of President William Lai’s (賴清德) inauguration on May 20. The title of the rally could be loosely translated to “May 18 recall fraudulent goods” (518退貨ㄌㄨㄚˋ!). Unlike in English, where the terms are the same, “recall” (退貨) in this context refers to product recalls due to damaged, defective or fraudulent merchandise, not the political recalls (罷免) currently dominating the headlines. I attended the rally to determine if the impression was correct that the TPP under party Chairman Huang Kuo-Chang (黃國昌) had little of a

At Computex 2025, Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang (黃仁勳) urged the government to subsidize AI. “All schools in Taiwan must integrate AI into their curricula,” he declared. A few months earlier, he said, “If I were a student today, I’d immediately start using tools like ChatGPT, Gemini Pro and Grok to learn, write and accelerate my thinking.” Huang sees the AI-bullet train leaving the station. And as one of its drivers, he’s worried about youth not getting on board — bad for their careers, and bad for his workforce. As a semiconductor supply-chain powerhouse and AI hub wannabe, Taiwan is seeing