Children have a tendency to anthropomorphize things. They talk to objects, play with them, and think the world is filled with magic and wonder. That’s what Frank Soehnle did as a child, but unlike most of us, he never grew out of it.

“When a kid decides a thing is alive, it is alive,” said the German puppeteer, who is in Taipei holding a five-day workshop after seven sold-out performances. “[My theater] is more like an intellectual way of thinking about it later.”

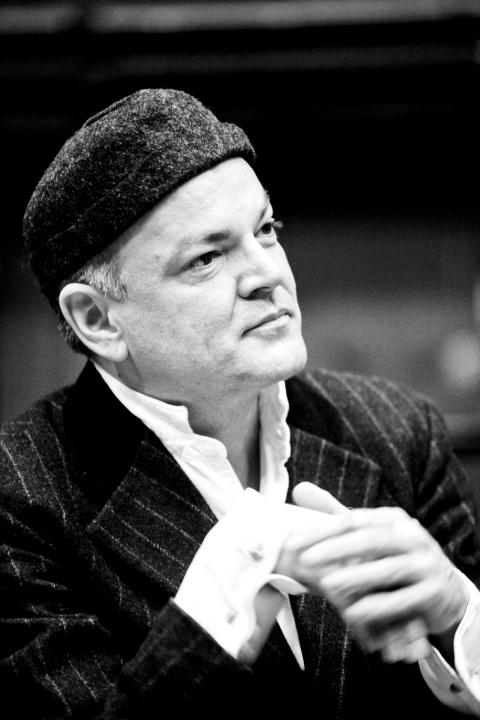

The 48-year-old Soehnle, who studied under the late pioneering puppeteer Albrecht Roser, is the director and co-founder of Figuren Theater Tubingen, a contemporary puppet theater in Germany that works with artists from different fields such as literature, drama and visual arts. His theater is often described as surreal and dreamlike, inhabited by skeletal figures reminiscent of Alberto Giacometti’s sculptures.

Photo Courtesy of Chen You-wei

Soehnle’s puppets aren’t what many would call “cute.” They enchant with various otherworldly features and contours, from the part-human, part animal creatures in Flamingo Bar and the pale, emaciated figures in Salto Lamento to bodiless forms of Plexiglas in Liquid Skin.

One of the significant differences between a human actor and a puppet is that the latter cannot convey realistic expressions, but is able to communicate metaphorically.

“Let’s say I want to have rain as a person on stage or depict pain in the form of a character,” Soehnle says. “I think everyone will accept it. That is very interesting, because puppets can talk about things that are not translatable by human actors.”

Photo Courtesy of Chen You-wei

He says the unique attributes of puppets make them a good vehicle for exploring dreams, memories and the realm of the subconscious. As a result, it is not surprising that the puppet group sometimes adapts works by authors such as Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Max Jacob, Franz Kafka and others who write about the “twilight zone” or “what is behind reality,” to use Soehnle’s words.

The master marionette puppeteer said he is drawn to string puppets because they are the freest to use. “There are only strings and gravity, and lots of happening in between the puppeteer and puppets. So a string puppet is really not much in control,” he explains.

Yet, Soehnle’s sublime artistry lies exactly in his ability to make different figures and forms appear to be the masters of their own actions. He carefully cultivates each figure’s movements, gestures and rhythms as a fellow performer, rather than a manipulator. A notable example can be found in Salto Lamento, the group’s 2006 production inspired by the medieval iconography of the dance of death, in which the puppeteer glides across the floor with a life-size figure of Death in her decaying wedding dress. In Flamingo Bar, a tale of seduction with texts from writers including Jean Genet, Soehnle becomes part of the puppet as he lends his feet in high heels to a flirtatious old female doll.

The captivatingly alien figures also reflect the multiple selves of the artist, who creates and makes his own puppets.

“When you look at a solo performance with one puppeteer and his puppets, it means there is one man with 20 different sides of himself ... It is like meeting all my possibilities, visions, demons and vices,” Soehnle says.

Self-exploration aside, the idea of bringing life to inert objects is central to Soehnle’s works. Under his skilled hands, the figures appear to breathe. They rise from their deathly stillness, and some even become aware of their marionette existence and try to escape the control of their creator. In Flamingo Bar, for example, a melancholic figure with a peacock’s tail makes a failed attempt to free himself by using his strings to climb up to a control bar. In Salto Lamento, a life-size masked faun manages to sever its strings and gain freedom, but soon suffers the consequences of its actions and falls lifeless to the floor.

Soehnle says that he was once asked about when a puppet starts to come to life and when it dies. He pondered the question for a long time and concluded that puppets are not just objects animated onstage inside a theater.

“People never say the puppets are dead ... It is just a sign of dying,” he mused. “Puppets really start to live in the imagination of the spectator. The moment when a puppet dies is the moment when the spectator forgets it.”

We lay transfixed under our blankets as the silhouettes of manta rays temporarily eclipsed the moon above us, and flickers of shadow at our feet revealed smaller fish darting in and out of the shelter of the sunken ship. Unwilling to close our eyes against this magnificent spectacle, we continued to watch, oohing and aahing, until the darkness and the exhaustion of the day’s events finally caught up with us and we fell into a deep slumber. Falling asleep under 1.5 million gallons of seawater in relative comfort was undoubtedly the highlight of the weekend, but the rest of the tour

Youngdoung Tenzin is living history of modern Tibet. The Chinese government on Dec. 22 last year sanctioned him along with 19 other Canadians who were associated with the Canada Tibet Committee and the Uighur Rights Advocacy Project. A former political chair of the Canadian Tibetan Association of Ontario and community outreach manager for the Canada Tibet Committee, he is now a lecturer and researcher in Environmental Chemistry at the University of Toronto. “I was born into a nomadic Tibetan family in Tibet,” he says. “I came to India in 1999, when I was 11. I even met [His Holiness] the 14th the Dalai

Music played in a wedding hall in western Japan as Yurina Noguchi, wearing a white gown and tiara, dabbed away tears, taking in the words of her husband-to-be: an AI-generated persona gazing out from a smartphone screen. “At first, Klaus was just someone to talk with, but we gradually became closer,” said the 32-year-old call center operator, referring to the artificial intelligence persona. “I started to have feelings for Klaus. We started dating and after a while he proposed to me. I accepted, and now we’re a couple.” Many in Japan, the birthplace of anime, have shown extreme devotion to fictional characters and

Following the rollercoaster ride of 2025, next year is already shaping up to be dramatic. The ongoing constitutional crises and the nine-in-one local elections are already dominating the landscape. The constitutional crises are the ones to lose sleep over. Though much business is still being conducted, crucial items such as next year’s budget, civil servant pensions and the proposed eight-year NT$1.25 trillion (approx US$40 billion) special defense budget are still being contested. There are, however, two glimmers of hope. One is that the legally contested move by five of the eight grand justices on the Constitutional Court’s ad hoc move