On the death of General Franco in 1975, Joan Miro was asked what he had done to promote opposition to the dictator, who had ruled Spain for nearly 40 years. The artist answered simply: “Free and violent things.”

The first major Miro exhibition in England for nearly 50 years, which opens at Tate Modern next month, will cast light on that answer. Miro is not always thought of as a political painter, in the broad or the narrow sense. He was not a creator of manifestos, or a signer of petitions; he was not given to provocative gesture like his contemporary Salvador Dali, nor did he pursue his passions at all costs, like his sometime mentor Picasso.

For most of the second half of his long life (he died in 1983 at the age of 90), Miro painted in his studio in Palma, Mallorca, charting a unique course among the movements in postwar painting, and always looking very much his own man.

Photo: Bloomberg

Politics was for Miro, however, unavoidable, an accident of birth. He was the son of a blacksmith and jeweler who lived on the harborside in Barcelona. He came of age with the Catalan independence movement, and shared its deep-rooted sense of the possibilities of liberty. To begin with, he identified this freedom with internationalism; he longed to be in Paris. But once he had escaped, he held on to his identity as a Catalan, as a freedom fighter, all the more devoutly and from it developed an intimate visual language that sustained him all of his working life.

The Tate show will concentrate on three periods of Miro’s constantly re-imagined career: his formative years in Catalonia; his exile in Paris in the years of the Spanish civil war and the outbreak of the second world war; and his enthusiasm for the radicalism of the 1960s, when he was approaching the late period of his work. Marko Daniel, the co-curator of the exhibition, which will bring together more than 150 works in collaboration with the Miro Foundation in Barcelona, hopes that it will be “a perspective not just on Miro but on the turbulence of the 20th century, the way an artist’s life might be shaped by proximity to these great political upheavals.”

The title of the show, Joan Miro: The Ladder of Escape, comes from a painting, one of a series, that Miro began in 1939 as the Nazi forces were advancing into France. He was living in Normandy at that time and had begun the works as a kind of personal defense against what he knew to be the horrors to come. The series of paintings dwelt on his profound internal sense of connections between things, an entirely singular private universe that he called the Constellations. When he eventually fled with his wife and daughter on the last train out of Paris for Spain, the paintings were rolled under his arm.

Photo: Bloomberg

Miro’s instinct for political engagement, though heartfelt and full of risk, often lays in these gestures of withdrawal, of self-defense. Andre Breton, the surrealist, once referred to Miro, for good and bad, as a case of “arrested development,” a childlike artist. The label stuck for a long time but this exhibition should go a long way to revealing how hard-won Miro’s apparent playfulness was. The ladder in that borrowed exhibition title had long been for him an emergency exit to the safe house of his imagination. In a 1936 interview, with the Spanish civil war a looming reality, he spoke of the need to “resist all societies... if the aim is to impose their demands on us.” The word “freedom has meaning for me,” he said, “and I will defend it at any cost.”

Though he was capable of making propaganda images for the Catalan and republican causes, this sense of absolute individual liberty was as much about a sense of wonder at the world; you could find it, he believed, “wherever you see the sun, a blade of grass, the spirals of the dragonfly. Courage consists sometimes of staying close to nature, which could not care less about our disasters.” In this spirit Miro created for himself the alter ego of a Catalan peasant, indefatigable and ribald, wild bearded under a barretina, the red cap of the rural radical. The surface of his life, despite the great fractures of the times in which he lived, was relatively orderly and measured, but you do not have to look for long at his work, including the pictures on these pages, to see that he reserved all of his formidable energies for his painting.

Five short essays on representative works by Miro

Nord-Sud, 1917

Miro made this painting in 1917, when he was living in his native Barcelona and dreaming of moving to Paris. He was in the final year of his national service as a soldier; Spain was not involved in World War I, and he was frustrated that the fighting in France had put his ambitions to enlist in the Parisian avant-garde on hold. After a period of depression, he had given up on the career in business that his father had planned for him, and had spent the previous four years, when not in uniform, painting full-time; he had that premature, 24-year-old’s sense that life was already passing him by. The presence in his painting of the journal Nord-Sud — founded in Paris that year by the poet Guillaume Apollinaire among others — hints both at this anxiety, and at a solidarity with the ideals of freedom the magazine represented.

The caged bird behind it is faced with an open door, but has not yet flown: “I must tell you,” Miro wrote to his friend and fellow painter EC Ricart in 1917, “that if I have to live much longer in Barcelona I will be asphyxiated by the atmosphere - so stingy and such a backwater (artistically speaking).”

Miro was, above all, desperate, in the spirit of the moment, to be part of an -ism, or, better, to create one. Impressionism was dead, he suggested: “Down with weeping sunsets in canary yellow ... Down with all that, made by crybabies!” He was already anticipating the demise of cubism, futurism and fauvism (though the latter in particular has a strong influence on his painting here). The scissors are open ready for him to cut ties with the past and present, with Catalonia (represented in the characteristic vase), and with Goethe-esque rites of passage. But his hopes of finding that new style, that new way of painting seemed to be beyond him, and to the north.

Two years later Miro still found himself maddeningly caught in this limbo. When Miro eventually made it to Paris, in 1920, he called on Picasso, whom he had never met, but whose mother was a family friend in Barcelona. Picasso looked out for him, bought a painting that Miro showed him, and helped him into the radical society he had dreamt of. Within a year, Miro’s tiny studio at rue Blomet received regular visits from his new friends: the poet Paul Eluard, the playwright Antonin Artaud and the artist Tristan Tzara. Sud had found his way Nord.

The Farm, 1921

“When I first knew Miro,” Ernest Hemingway wrote in 1934, “he had very little money and very little to eat, and he worked all day every day for nine months painting a very large and wonderful picture called The Farm.”

Miro found that his life in Paris allowed him to understand his Catalan roots, that formative light that had seemed so oppressive, with a new and startling clarity. His parents had bought a country house in the Catalan mountains at Mont-roig in 1910, in part to help him recover from depression. It was where he learned to look at the natural world. In The Farm, he later recalled, “I wanted to put everything I loved about the country in the canvas, from a huge tree to a tiny little snail.” He brought dry grasses up from Mont-roig to Paris so he could “finish the painting after nature.”

Because he was working so hard on the painting during the day he took to boxing in the evening at a local gym as a way of relaxing. Among his sparring partners was Hemingway. Miro, so the story goes, impressed the writer first with his punching and then with his painting.

Hemingway was determined to buy The Farm. He agreed with Miro’s dealer to pay 5,000 francs for it, which, he recalled, “was four thousand two hundred and fifty francs more than I had ever paid for a picture.” When it was time to make the last payment he risked losing the painting because he didn’t have the money. On the final day he trawled around every bar he knew in Paris, with his friend John Dos Passos, borrowing cash, and eventually raised the funds.

“After Miro had painted The Farm,” Hemingway wrote, “and after James Joyce had written Ulysses, they had a right to expect people to trust the further things they did, even when people did not understand them.”

The Catalan Landscape (The Hunter), 1923-1924

Only two years after he painted The Farm, Miro was spending more time back in Catalonia, trying out ways to distil the essence of his Catalan identity still further. He had become friends in Paris with Andre Breton, finding his once longed-for -ism. Surrealism, an artistic response to the power of dreams and the subconscious, was only a brief obsession for Miro but its ideas informed his painting of the mid-1920s, and his methods thereafter.

The compulsive detailing of his earlier painting had by the time of The Hunter become a kind of playful shorthand. He had a powerful sense of the emptiness of his remembered landscape, animated only momentarily by human action; life becomes explicable as a diagrammatic series of gestures and relationships, “the underlying magic,” as Miro described it, and he developed a way of painting that seemed to respond to those energies. He was in search of the essence of things. In The Hunter, his Catalan peasant alter ego is captured simultaneously in the act of shooting a rabbit for his cooking pot and fishing for a sardine for his barbecue.

Andre Breton acquired The Hunter in 1925, the year after he wrote his Surrealist Manifesto. He believed that Miro had found a way to depict the “poetic reality” of life, in ways that his manifesto had described, but which he had not fully imagined. Miro was not much interested in manifestos, though.

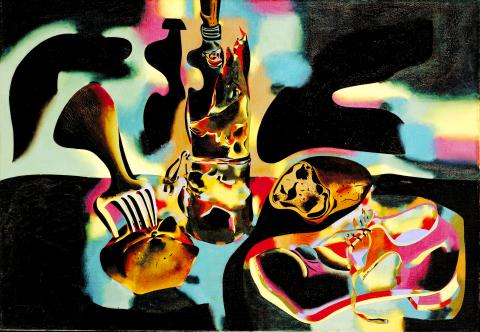

Still Life With Old Shoe, 1937

For a while in his 20s and 30s, Miro had felt his freedom almost unconstrained in Paris. When he returned to the city in 1934, though, now married and a father, he carried a sense of foreboding about the state of Spain and Europe: “I had this unconscious feeling of impending disaster,” he later wrote. “Like before it rains; a heavy feeling in the head, aching bones, an asphyxiating dampness.”

From the beginning of that year, Miro found himself unable to draw anything but monsters; the human figure became a grotesque of teeth and genitals. The margins of his sketchbooks are populated with visions of nightmarish couplings and weirdly erotic subhuman bodies. He had a sense of himself as prophetic in some way, and was troubled by these portents.

The outbreak of civil war in Spain and the rise of fascism across Europe confirmed his worst fears. He contributed images for propaganda posters, the raised fist of the Catalan peasant, for the republican cause.

But in Paris, in 1937, where he had gone with his wife and daughter to escape the bombing, Miro now found himself a prisoner from the terror at home, and he was at a loss to know how to respond.

He felt he had to begin again from first principles. He came across a gin bottle in the street, brought it home to his apartment, and began to paint a still life, which quickly took on the atmosphere of his apocalyptic anxieties. The painting took him five months to complete from January 1937.

The Escape Ladder, 1940

In 1939, at the outbreak of World War II, Miro and his family moved to Varengeville on the Normandy coast, a few kilometers from Dieppe. Georges Braque was a neighbor. The village was subject to a blackout, and that fact prompted Miro’s most luminous and affecting series of paintings, the Constellations.

Painted on paper, the pictures create the most vibrant expression of Miro’s inner universe, with its by now recognizable system of codes and symbols. The ladder of this painting had always been a fascination for him; it had acted as a metaphor for his attempts to put his painting on a different plane of understanding the world, as a path away from mundane realism. Now it becomes an even more urgent gesture toward flight: “I felt a deep desire to escape,” he wrote of that period. “I closed myself within myself purposely. The night, music and the stars began to play a major role in suggesting my paintings.”

Last week, on the heels of the recall election that turned out so badly for Taiwan, came the news that US President Donald Trump had blocked the transit of President William Lai (賴清德) through the US on his way to Latin America. A few days later the international media reported that in June a scheduled visit by Minister of National Defense Wellington Koo (顧立雄) for high level meetings was canceled by the US after China’s President Xi Jinping (習近平) asked Trump to curb US engagement with Taiwan during a June phone call. The cancellation of Lai’s transit was a gaudy

Following the shock complete failure of all the recall votes against Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers on July 26, pan-blue supporters and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) were giddy with victory. A notable exception was KMT Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫), who knew better. At a press conference on July 29, he bowed deeply in gratitude to the voters and said the recalls were “not about which party won or lost, but were a great victory for the Taiwanese voters.” The entire recall process was a disaster for both the KMT and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). The only bright spot for

From Godzilla’s fiery atomic breath to post-apocalyptic anime and harrowing depictions of radiation sickness, the influence of the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki runs deep in Japanese popular culture. In the 80 years since the World War II attacks, stories of destruction and mutation have been fused with fears around natural disasters and, more recently, the Fukushima crisis. Classic manga and anime series Astro Boy is called “Mighty Atom” in Japanese, while city-leveling explosions loom large in other titles such as Akira, Neon Genesis Evangelion and Attack on Titan. “Living through tremendous pain” and overcoming trauma is a recurrent theme in Japan’s

As last month dawned, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was in a good position. The recall campaigns had strong momentum, polling showed many Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers at risk of recall and even the KMT was bracing for losing seats while facing a tsunami of voter fraud investigations. Polling pointed to some of the recalls being a lock for victory. Though in most districts the majority was against recalling their lawmaker, among voters “definitely” planning to vote, there were double-digit margins in favor of recall in at least five districts, with three districts near or above 20 percent in