The loud groans of a man masturbating prompt passersby to crane their heads and a security guard from an adjacent building to wander over to see what’s up.

Inside Project Fulfill Art Space (就在藝術空間), artist, curator and educator Wang Fu-jui (王福瑞) mans a makeshift recording studio complete with mixers, microphones, a megaphone and speakers belting out a variety of sounds, including a track by Japanese noise project The Gerogerigegege of a male furiously pleasuring himself. Wang aims to blow the minds, or eardrums (or both), of the six university-aged participants who have arrived for a workshop on sound titled Noise and the Other (噪音與他者).

The three-and-a-half-hour session forms part of The More the Merrier (多多益善), a monthlong project organized by German artist and curator Jens Maier-Rothe and New York-based Taiwanese sound artist Wang Hong-kai (王虹凱) that is intended to spark debate on the uses and abuses of sound. The project’s workshops, and a symposium at the end of the month, are open to the public.

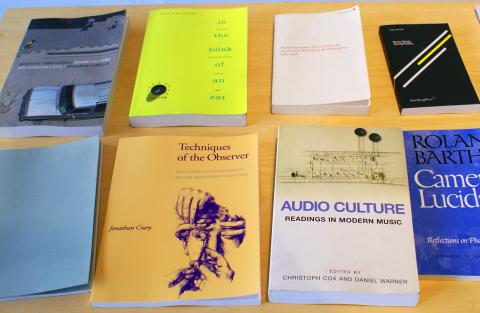

Photo: Noah Buchan, Taipei Times

Discussion of using sound in art, says Maier-Rothe, is in its infancy.

“In Taiwan, discourse on the use of sound in art is almost non-existent,” said Wang Hong-kai, who was recently chosen to represent the country at the 2011 Venice Biennale. “Even though sound companies are vibrant and active, I’ve hardly come across an occasion where people can gather to do a collective exercise or workshop [on the topic].”

The More the Merrier, the organizers hope, will help promote sound as a viable medium to “explore the politics of recording as a collective activity,” said Wang Hong-kai.

Photo: Noah Buchan, Taipei Times

Noise and the Other, the first installment of the project, is an investigation into the history of “acoustic propaganda” in post-World War II Taiwan and the “presence of ideologically charged messages in [the] acoustic public space today,” according to the exhibition’s publicity material.

Great, I thought: From the authoritarian-era suppression of Hoklo (also known as Taiwanese), Hakka and Aboriginal languages to the loudspeakers on Kinmen blasting out propaganda towards China, the theme had all the potential of spurring a lively debate, and could easily segue into a discussion on the contemporary uses of sound, such as during elections or at the night market.

Alas, it didn’t turn out that way.

Photo: Noah Buchan, Taipei Times

Wang began the workshop with some heavily distorted sound that reminded this reviewer of 1970s punk and 1990s grunge. The participants’ reactions ran from confusion to enthusiasm. To this reviewer, it was just noise, and I got lost in Wang Fu-rui’s convoluted discussion about why he was presenting these sounds.

In an example of just how embryonic the subject of sound in art is, the workshop barely moved beyond talking about Wang Fu-rui’s beloved Japanese noise project.

Still, it was an interesting, if somewhat bizarre, start.

Then came a group discussion about our perspectives on the differences between noise and sound (the former, we generally agreed, is an unwanted version of the latter) and our opinions on sounds that are associated with Taiwan (the melodies that accompany garbage trucks or the clickety-clack of mahjong tiles). The politics of sound was tangentially touched on when we discussed the four languages used to announce stops on Taipei’s Mass Rapid Transport system.

Then one final track by The Gerogerigegege. The last few minutes were devoted to participants using a bullhorn to speak, or scream, their thoughts about sound into a microphone.

Following the workshop, I asked the organizers how they thought it had gone.

“If you were to do a show like this in New York, it would probably be a little boring,” said Maier-Rothe. “People are saturated with this kind of practice ... Participatory practice is so yesterday. But here, people are almost thirsty for something like this. They really want to come and get together and discuss their ideas.”

This Saturday’s workshop, titled Two Is Alright (哼哈二將), will be moderated by artist Jao Chia-en (饒加恩) and will explore participants’ roles in public spaces.

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) hatched a bold plan to charge forward and seize the initiative when he held a protest in front of the Taipei City Prosecutors’ Office. Though risky, because illegal, its success would help tackle at least six problems facing both himself and the KMT. What he did not see coming was Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (將萬安) tripping him up out of the gate. In spite of Chu being the most consequential and successful KMT chairman since the early 2010s — arguably saving the party from financial ruin and restoring its electoral viability —

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,