When Taiwan’s four best-selling newspapers published gruesome photos of a crocodile clutching a zoo veterinarian’s severed arm in its mouth in 2007, legislators from across party lines called on the media to do a better job of self-regulation.

The United Daily News, Apple Daily and China Times published the photos without digital manipulation to blur the gore, while the Liberty Times (the Taipei Times’ sister newspaper) obscured some of the detail.

Three years later, child welfare advocates are citing the publication of those images — and a host of others — as justification for proposed amendments to the Children and Youth Welfare Act (兒童及少年福利法) that would impose new regulations on the media. They say the changes are necessary to protect the “mental and physical” health of children. Industry professionals, however, say the changes, which passed their first legislative reading on Nov. 17, would restrict media freedoms.

Photo: TAIPEI TIMES

At the heart of the controversy is Article 44 of the proposed amendments, which would ban newspapers from publishing stories and pictures describing “crimes, the use of drugs, suicide … bloodshed, erotica, lewdness or forced sex in detail.”

Article 90 of the draft legislation goes on to state that offenders could be fined between NT$100,000 and NT$500,000 for each offense.

The greater good?

“What do they mean by details? To what extent are you going to make these kinds of descriptions illegal? There is no precedence for newspapers,” said Liu Ching-yi (劉靜怡), an associate professor in the Graduate Institute of National Development at National Taiwan University and an expert on human rights and media law. “In [Taiwan’s] law, pornography is not illegal per se. Obscenity is illegal — but erotica (色情) is used a lot in Article 44 … That is very difficult for judges to interpret.”

Proponents of the draft amendments say that since the Publishing Law (出版法) — legislation enacted while the Chinese Nationalist Party still controlled China that muzzled the press and was used to stamp out political dissent during the Martial Law era — was repealed in 1999, the case for regulation has grown stronger.

“After the Publishing Law was abolished, there has not been any specific law to regulate newspapers,” said Harold Li (李宏文), a chief research officer with the Child Welfare League Foundation (兒童福利聯盟基金會), an NGO that helped formulate the amendments. “The media environment in Taiwan has changed for the worse since 2003 when the Children Welfare Act (兒童福利法) and the Adolescent Welfare Act (少年福利法) were combined” to form the Children and Youth Welfare Act.

Li said that the original draft didn’t include articles regulating newspapers, “but they were added following numerous complaints from members of the public about those crocodile photos.”

More than anything else, though, it is the idea underpinning the amendments that concern media professionals and press freedom advocates.

“This is another kind of Publishing Law,” Liu said.

While some media outlets would rather the amendments were dropped entirely, they say that if the Children and Youth Welfare Act is to be changed, those changes should address their concerns.

“If this law passes, it will forbid us from reporting any news in detail,” said Hsiang Kuo-ning (項國寧), a spokesman for the United Daily News.

Mark Simon, commercial director of Next Media Animation, which belongs to the Next Media Group, owner of the Apple Daily, was more blunt in his assessment.

“Let’s be honest, this has far more to do with control of media than child welfare. This law is designed to restrict news coverage for all of Taiwan,” he wrote in an e-mail interview. “It is not a decency law. It is in fact a law that will impact the reporting of every crime, every accident [and] every misadventure by a politician. Editors will not be, as they should be, subject to laws of decency, but to a lower standard, the tastes of a ruling political class.”

Liu agrees.

“I have this uncomfortable feeling that the government is using child and youth protection as an excuse to implement some kind of regime — though I’m not sure what kind of regime it is,” she said. “There shouldn’t be a law [regulating newspapers] because there are too many other laws. Defamation, for example. There are laws governing that. Very strict laws regulating what you can say in the newspaper.”

Standard–bearers

For Li and the legislators who drafted the proposed amendments, Article 44 is necessary as the press is, they say, unable or unwilling to adequately regulate itself.

“We cannot just sit around and do nothing because media outlets argue that this legislation erodes the freedom of speech,” said Li.

After receiving complaints from press freedom advocates, the legislature returned the two articles to the Ministry of the Interior’s Bureau of Child Welfare (內政部兒童局) for revision before they are put to a second reading.

In a copy obtained by the Taipei Times, the new draft, which is scheduled to be debated today at a public hearing chaired by Minister of the Interior Jiang Yi-huah (江宜樺), drops the term “crime” (犯罪) and includes a new paragraph stating that a committee could be convened to help the government determine whether the law had been violated. Left unclear, however, is who would be appointed to the committee and whether it would wield any legal powers.

But Article 44 remains largely unaltered, and though the proposed changes need to clear two more readings to become law, they seem likely to because they enjoy cross-party support.

Water management is one of the most powerful forces shaping modern Taiwan’s landscapes and politics. Many of Taiwan’s township and county boundaries are defined by watersheds. The current course of the mighty Jhuoshuei River (濁水溪) was largely established by Japanese embankment building during the 1918-1923 period. Taoyuan is dotted with ponds constructed by settlers from China during the Qing period. Countless local civic actions have been driven by opposition to water projects. Last week something like 2,600mm of rain fell on southern Taiwan in seven days, peaking at over 2,800mm in Duona (多納) in Kaohsiung’s Maolin District (茂林), according to

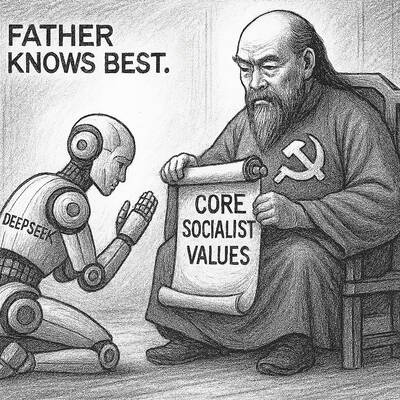

It’s Aug. 8, Father’s Day in Taiwan. I asked a Chinese chatbot a simple question: “How is Father’s Day celebrated in Taiwan and China?” The answer was as ideological as it was unexpected. The AI said Taiwan is “a region” (地區) and “a province of China” (中國的省份). It then adopted the collective pronoun “we” to praise the holiday in the voice of the “Chinese government,” saying Father’s Day aligns with “core socialist values” of the “Chinese nation.” The chatbot was DeepSeek, the fastest growing app ever to reach 100 million users (in seven days!) and one of the world’s most advanced and

The latest edition of the Japan-Taiwan Fruit Festival took place in Kaohsiung on July 26 and 27. During the weekend, the dockside in front of the iconic Music Center was full of food stalls, and a stage welcomed performers. After the French-themed festival earlier in the summer, this is another example of Kaohsiung’s efforts to make the city more international. The event was originally initiated by the Japan-Taiwan Exchange Association in 2022. The goal was “to commemorate [the association’s] 50th anniversary and further strengthen the longstanding friendship between Japan and Taiwan,” says Kaohsiung Director-General of International Affairs Chang Yen-ching (張硯卿). “The first two editions

It was Christmas Eve 2024 and 19-year-old Chloe Cheung was lying in bed at home in Leeds when she found out the Chinese authorities had put a bounty on her head. As she scrolled through Instagram looking at festive songs, a stream of messages from old school friends started coming into her phone. Look at the news, they told her. Media outlets across east Asia were reporting that Cheung, who had just finished her A-levels, had been declared a threat to national security by officials in Hong Kong. There was an offer of HK$1m (NT$3.81 million) to anyone who could assist