There is an art to writing a gallery or museum show’s informational material. The exhibition’s essence and the tradition within which it fits must be precisely conveyed in a few paragraphs. The task is doubly important for a show about ink painting, whose heritage can sometimes seem impenetrable.

For its annual ink painting exhibitions, the Taipei Fine Arts Museum (TFAM — 台北市立美術館) usually excels at contextualizing this tradition and presenting its contemporary manifestations as an art form worthy of continued interest.

Unfortunately, the introductory pamphlet for Time Unfrozen: From Liu Kuo-sung to New Media Art (白駒過隙‧山動水行─從劉國松到新媒體藝術) misses the mark, confusing readers with cliches and bizarre statements.

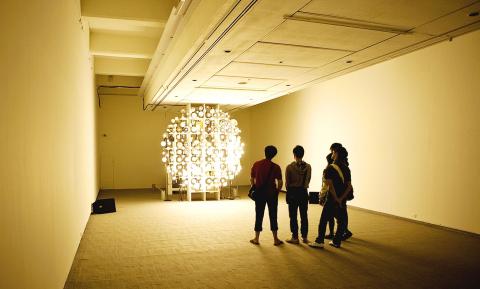

Photo: courtesy of TFAM

The pamphlet describes the exhibition as an exploration of “the modern force of Oriental aesthetics” through the work of “19 artists [groups] from the four Chinese regions on either side of the Taiwan Strait” working in sound, light, video and interactive installation.

“For the last thousand years, our view of the universe has been contained in Oriental ink art. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the West described the Oriental view of nature with words like atmospheric, organic, transparent, spiritual, tranquil and timeless,” it states.

Why draw on discredited and outmoded 19th and 20th-century Western (not Taiwanese, or Chinese) definitions to introduce a show about ink painting?

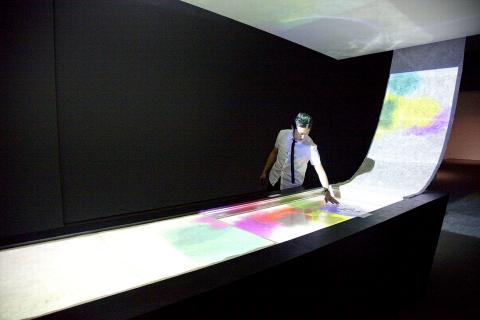

Photo courtesy of TFAM

In an easily understandable essay on the ink painting tradition, published in the mid-20th century, art historian Michael Sullivan wrote that it is “important to realize that Chinese painting has not one style but many” — a lesson that seems lost on TFAM.

Sullivan continues: “Its unique quality lies in the gradual evolution of a language of pictorial abstractions, or symbols, for the representation of outward appearance which, once completely mastered, made it unnecessary for the Chinese artist to rely for inspiration upon direct observation of natural forms.” Easy to comprehend, yet sophisticated enough to make the reader think.

Or how about this, from last year’s Open Flexibility: Innovative Contemporary Ink Art (開顯與時變-創新水墨藝術展) exhibition: “Artists use ink to express their thoughts and perceptions of actual experiences in their individual lives, and in the process of creating, face rigorous challenges,” including “how to transcend the limitations of a traditional medium” in a contemporary context. Again, a clear and concise summation.

Photo courtesy of TFAM

What the curator of Time Unfrozen tries to do in the exhibition’s introduction is baffling. “The younger generation is quick to adore time, which could not be measured but which now has been measured,” the pamphlet says.

The purpose of Time Unfrozen, as far as this reviewer can tell, is to show that like Liu Kuo-sung’s early experiments with ink painting, the “younger generation” can adapt technology to this “timeless” medium.

And as this exhibit demonstrates, in many cases it can. Wu Chi-tsung’s (吳季璁) series of single-channel videos meditate on classic ink painting subjects, such as pine trees and orchids, reflecting the artist’s belief that ink painting can be embraced by technology without being overwhelmed by it. Lin Jiun-ting’s (林俊廷) interactive installation videos of cranes and dragons are subtle attempts to bring motion to these mythological creatures, and visitors can connect with them in the present.

Qiu Anxiong’s (邱黯雄) video, New Book of Mountains and Seas Part II (新山海經二), contemporizes Classics of Mountains and Seas (山海經), an ancient Chinese scientific and geographical treatise. Qiu created 6,000 ink drawings over four years, individually photographed them and turned them into a 30-minute, three-channel video. The result is an astonishing, albeit frightening, allegory of contemporary society replete with environmental degradation, genetically altered beasts and no shortage of corpses.

But these technological investigations are mostly lost amid other works that could be more accurately described as multi-disciplinary designs because of their resemblance to special effects from television or cinema, such as Funky Light (光怪), a light and sound collaborative show by Digital Arts Center (數位藝術中心) and four artists.

And then there’s Formation of Consciousness (墨影意形) by Frankie Fan (范赫鑠) and xXtraLab Design Co (爻域互動科技設). The latter, according to its Facebook page, specializes in “commercial design HCI (Human-Computer Interaction) interfaces in museums, expositions and showrooms.” Though the technology deftly brings to life the medium of ink painting, it’s hard to escape the idea that Fan, who is xXtraLab Design Co’s general manager, is trying to drum up a little business for the company’s newest interactive technology.

Incidentally, the headline for a recent Central News Agency report on Fan’s company and its new technologies offer, read: “Digital arts promoted with interactive devices.” It might have been more appropriately titled: “Interactive devices promoted as digital art.”

Far more than an exhibition of ink painting, Time Unfrozen ends up exposing the questionable practice of promoting technological innovation as art. Though some works in the show follow an ink-painting tangent, others are overpowered by the gizmos used to make relevant what for many is a rarefied medium.

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,

Mongolian influencer Anudari Daarya looks effortlessly glamorous and carefree in her social media posts — but the classically trained pianist’s road to acceptance as a transgender artist has been anything but easy. She is one of a growing number of Mongolian LGBTQ youth challenging stereotypes and fighting for acceptance through media representation in the socially conservative country. LGBTQ Mongolians often hide their identities from their employers and colleagues for fear of discrimination, with a survey by the non-profit LGBT Centre Mongolia showing that only 20 percent of people felt comfortable coming out at work. Daarya, 25, said she has faced discrimination since she