Death in ancient Egypt was far from straightforward. A new and splendid exhibition at the British Museum — Journey Through the Afterlife: Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead — makes that clear.

Viewed from within the mummy case, the hereafter was strewn with pitfalls. The Book of the Dead was a post mortem self-help manual to get you safely through the tricky early stages to the Egyptian paradise, or Field of Reeds.

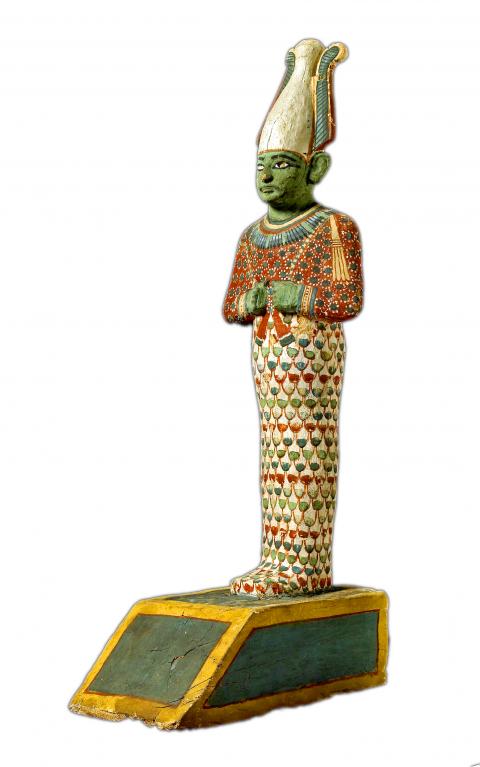

This is not the kind of show you can just relax and enjoy. There’s a steep learning curve, as there was for the occupants of the tombs in the Valley of the Kings. Renaissance Italian art isn’t really comprehensible without a smattering of Greco-Roman mythology and biblical events. Similarly, to appreciate Egyptian imagery, you have to assimilate a pantheon of gods (many beast-headed), plus numerous arcane rituals and beliefs.

photos: BLOOMBERG

So this exhibition involves work. On the other hand, it’s beautifully designed: The installation is in a maze-like series of spaces within the old Reading Room that evoke the gloom and mystery of Pharaonic architecture, though I could have done without the sci-fi sound effects.

The exhibits largely come from the museum’s own collection, the largest in the world (seldom displayed for conservation reasons). In Egyptologist terms, the Books of the Dead themselves are actually a bit newfangled, only appearing in the 17th century BC. That means they date from the New Kingdom (16th century BC to 11th century BC), or later — at which point Egyptian civilization already had been established for more than a millennium.

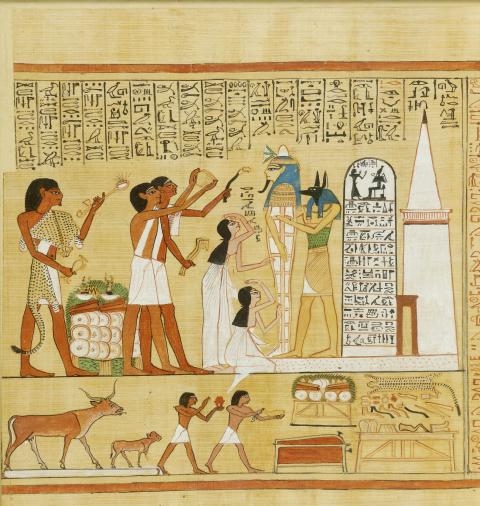

If not actually mass produced, the books (papyrus scrolls) were made in quantity and stayed in fashion on and off for 1,500 years. Thousands survive. Many have the weird quality — a consequence of the hot, arid Egyptian climate — of looking as if they had been written last week even though they are 3,500 years old. Often magnificently illustrated, they contain spells and hymns to the gods to avert the perils of afterlife.

photos: BLOOMBERG

There were plenty of perils and spells. The largest surviving example — The Greenfield Papyrus, made around 990 BC to 969 BC for Nesitanebisheru, daughter of a high priest — is 37m in length. Also on show are coffin cases and other accessories for the well-furnished tomb.

I emerged understanding the Ancient Egyptian cosmos a good deal better, though admittedly starting from a somewhat low base. Much of it seems strange, and also, if you come from a Judeo-Christian background, oddly familiar. The Egyptian paradise, an idealized version of the Nile Valley landscape, is reminiscent of the Garden of Eden and the Greek Elysian Fields.

The toughest test the dead faced was interrogation by 42 divine judges to whom one had to plead innocence of a long list of offenses. Among these was murder, of which Queen Nodjmet was definitely guilty. Amazingly, the museum has an incriminating letter on show beside her Book of the Dead.

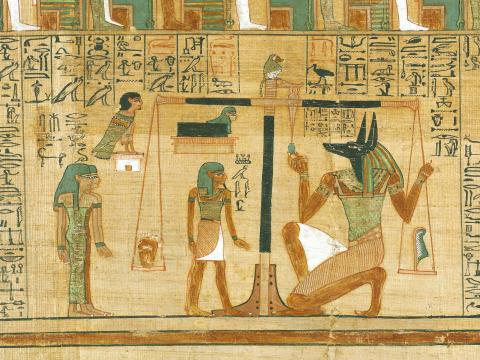

At this point, the heart — believed to be the site of consciousness — was weighed in a pair of scales much like those used in paintings of the Last Judgment. If these tipped the wrong way, you were prey to the Devourer, a nasty-looking customer with the head of a crocodile, forelegs of a lion and back end of a hippopotamus. But the Books of the Dead always show the owner arriving successfully in the Field of Reeds. Some things don’t change: Self-help manuals tend to look on the bright side.

June 2 to June 8 Taiwan’s woodcutters believe that if they see even one speck of red in their cooked rice, no matter how small, an accident is going to happen. Peng Chin-tian (彭錦田) swears that this has proven to be true at every stop during his decades-long career in the logging industry. Along with mining, timber harvesting was once considered the most dangerous profession in Taiwan. Not only were mishaps common during all stages of processing, it was difficult to transport the injured to get medical treatment. Many died during the arduous journey. Peng recounts some of his accidents in

“Why does Taiwan identity decline?”a group of researchers lead by University of Nevada political scientist Austin Wang (王宏恩) asked in a recent paper. After all, it is not difficult to explain the rise in Taiwanese identity after the early 1990s. But no model predicted its decline during the 2016-2018 period, they say. After testing various alternative explanations, Wang et al argue that the fall-off in Taiwanese identity during that period is related to voter hedging based on the performance of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Since the DPP is perceived as the guardian of Taiwan identity, when it performs well,

The Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) on May 18 held a rally in Taichung to mark the anniversary of President William Lai’s (賴清德) inauguration on May 20. The title of the rally could be loosely translated to “May 18 recall fraudulent goods” (518退貨ㄌㄨㄚˋ!). Unlike in English, where the terms are the same, “recall” (退貨) in this context refers to product recalls due to damaged, defective or fraudulent merchandise, not the political recalls (罷免) currently dominating the headlines. I attended the rally to determine if the impression was correct that the TPP under party Chairman Huang Kuo-Chang (黃國昌) had little of a

At Computex 2025, Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang (黃仁勳) urged the government to subsidize AI. “All schools in Taiwan must integrate AI into their curricula,” he declared. A few months earlier, he said, “If I were a student today, I’d immediately start using tools like ChatGPT, Gemini Pro and Grok to learn, write and accelerate my thinking.” Huang sees the AI-bullet train leaving the station. And as one of its drivers, he’s worried about youth not getting on board — bad for their careers, and bad for his workforce. As a semiconductor supply-chain powerhouse and AI hub wannabe, Taiwan is seeing