The ancient Greeks were passionate about representing the human body, and a current exhibition of cultural treasures takes viewers from crude fertility figurines dating back as early as 2600 BC to the pinnacle of representational skill and classical proportions achieved between 500 BC and 300 BC.

The Body Beautiful in Ancient Greece, which will be on display at the Library Building, National Palace Museum (國立故宮博物院圖書文獻大樓) until Feb. 7 next year, presents a rare opportunity to view 136 of the finest works from the vast collection housed at the British Museum in London.

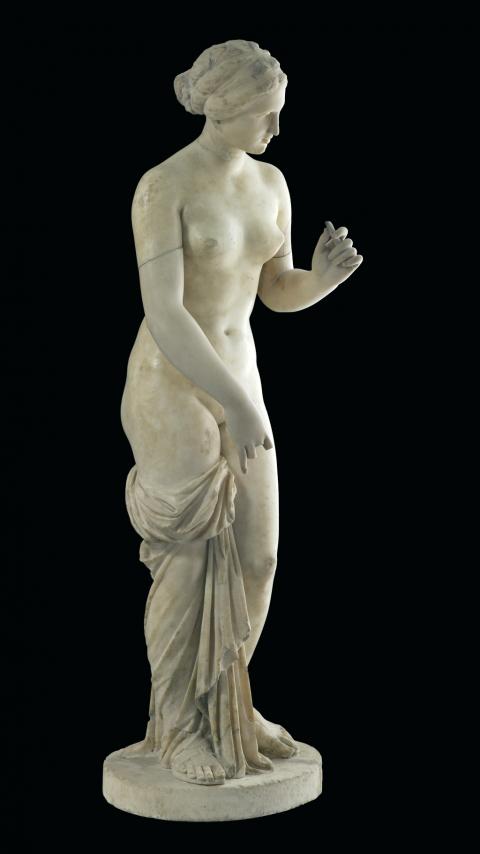

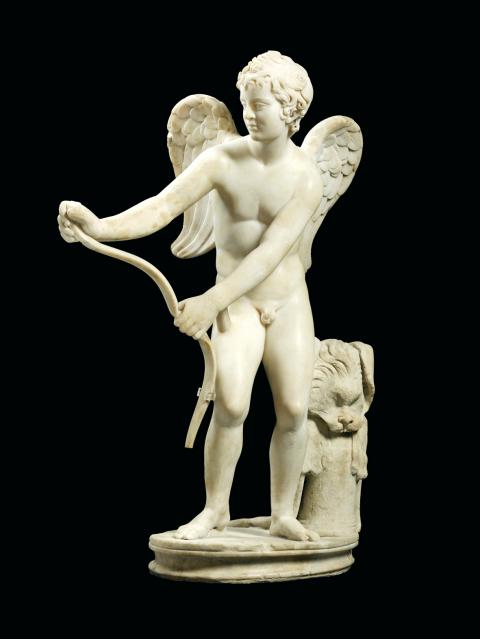

Ancient Greek sculpture, especially from the classical period, constitutes not only a representation of what are more often than not recognizably individuals, but also a fascination with the divine as expressed through the perfect proportions of the human being at his or her most beautiful.

Photo courtesy of NPM

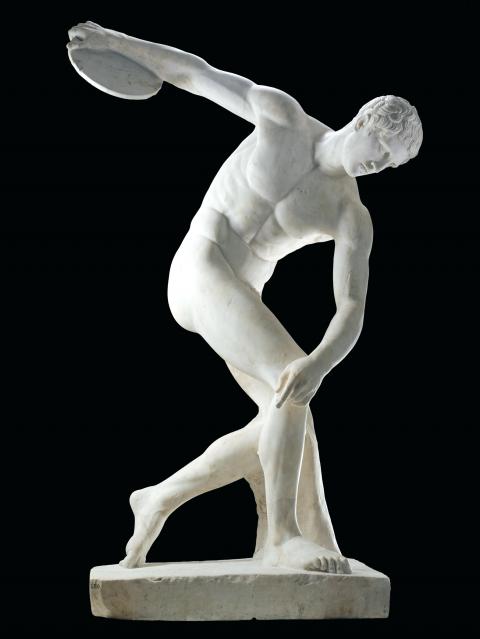

Many of the statues are presented in later marble copies of bronze originals, such as the discus thrower that adorns much of the publicity material for the exhibition. These were painstakingly duplicated from originals that were subsequently lost.

Some of the statues will be familiar to viewers from photographs, but the works benefit hugely from the ability to be seen in the round, which gives full expression to the composition that enables a work like the discus thrower to be simultaneously still and filled with dynamic tension.

The items in the exhibition are divided into 10 categories: the male body; the female body; the divine body; athletes; birth, marriage and death; love and desire; outsiders; Herakles; character and realism; and the human face.

Photo courtesy of NPM

The discus thrower, from the height of the classical period, is utterly composed and filled with an almost godlike beauty that seems to contemplate its own perfection. Toward the end of the classical period, Greek artists started to tire of such poise and sought a greater realism that threw divine proportions to the wind. A marble statuette of Socrates, with its high forehead, snub nose and thick lips, has none of the qualities that we associate with classical beauty, but strives for a photographic likeness, rejoicing in a warts-and-all representation of the great philosopher.

Some of the items on display give us an idea of life in ancient Greece, such as the delicately painted ceramic amphora given away as prizes at major athletic competitions, or the breast-shaped drinking vessels, which might have been used during a naughty night out by the successful athlete after the competition.

But The Body Beautiful is not a sociological exhibition, and explanatory material is kept to a minimum, allowing the viewer to focus on the physical presence of the objects, rather than be too much distracted by detailed explanations of the whys and wherefores of a particular object.

Photo courtesy of NPM

In the darkened space of the Library Building, the white marble statues seem to glow with inner life, and it is easy to become captivated by a posture or an expression without needing to know too much about it. The arrangement by theme rather than date also allows comparisons to jump out.

The exhibition itself shares some of the qualities of the works on display: elegantly composed and powerful despite its understated presence.

Photo courtesy of NPM

Behind a car repair business on a nondescript Thai street are the cherished pets of a rising TikTok animal influencer: two lions and a 200-kilogram lion-tiger hybrid called “Big George.” Lion ownership is legal in Thailand, and Tharnuwarht Plengkemratch is an enthusiastic advocate, posting updates on his feline companions to nearly three million followers. “They’re playful and affectionate, just like dogs or cats,” he said from inside their cage complex at his home in the northern city of Chiang Mai. Thailand’s captive lion population has exploded in recent years, with nearly 500 registered in zoos, breeding farms, petting cafes and homes. Experts warn the

The unexpected collapse of the recall campaigns is being viewed through many lenses, most of them skewed and self-absorbed. The international media unsurprisingly focuses on what they perceive as the message that Taiwanese voters were sending in the failure of the mass recall, especially to China, the US and to friendly Western nations. This made some sense prior to early last month. One of the main arguments used by recall campaigners for recalling Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers was that they were too pro-China, and by extension not to be trusted with defending the nation. Also by extension, that argument could be

Aug. 4 to Aug. 10 When Coca-Cola finally pushed its way into Taiwan’s market in 1968, it allegedly vowed to wipe out its major domestic rival Hey Song within five years. But Hey Song, which began as a manual operation in a family cow shed in 1925, had proven its resilience, surviving numerous setbacks — including the loss of autonomy and nearly all its assets due to the Japanese colonial government’s wartime economic policy. By the 1960s, Hey Song had risen to the top of Taiwan’s beverage industry. This success was driven not only by president Chang Wen-chi’s

Last week, on the heels of the recall election that turned out so badly for Taiwan, came the news that US President Donald Trump had blocked the transit of President William Lai (賴清德) through the US on his way to Latin America. A few days later the international media reported that in June a scheduled visit by Minister of National Defense Wellington Koo (顧立雄) for high level meetings was canceled by the US after China’s President Xi Jinping (習近平) asked Trump to curb US engagement with Taiwan during a June phone call. The cancellation of Lai’s transit was a gaudy