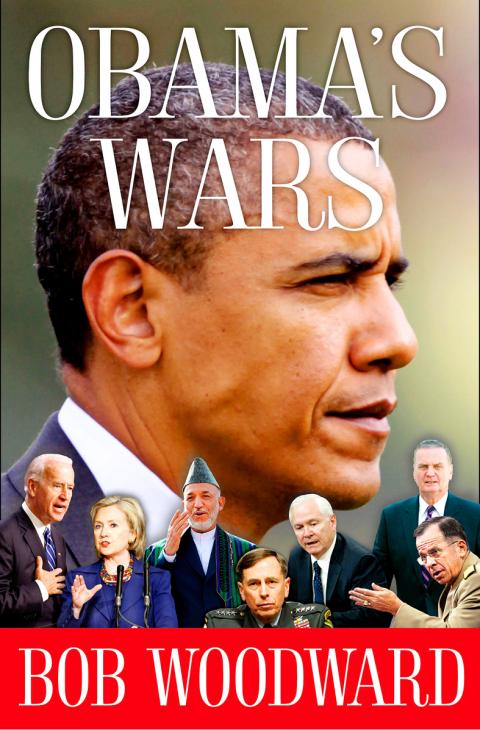

As a chronicler of American politics, Bob Woodward needs no introduction. Which is just as well for him, since without his name on the cover there is surely no way that Obama’s Wars would have been published. Disjointed and meretricious, Obama’s Wars seeks to tell a tale with no beginning or end, delivered without insight and written without narrative.

Churchill is supposed to have said that “jaw-jaw” is always better than “war-war,” but he never had to read Woodward on the subject. The jaw-jawing begins, sort of, with US President Barack Obama’s election in November 2008 — although the war in Afghanistan had already been going for seven years — and ends, sort of, with Obama’s announcement of 30,000 more US troops in December last year, with a resolution of the conflict far from clear.

In between this non-beginning and non-ending, Woodward’s unlucky readers are dragged through a succession of meetings about meetings, draft memos and PowerPoint presentations, charting the internal disagreements within the various arms of the US government. Briefly: the US military want the new president to increase the size of US forces in Afghanistan. But no one can agree on how big an increase, define the US’ military objectives or set a timetable. Eventually Obama gets fed up and dictates all three points.

If that brief summary makes Obama’s Wars sound coherent or even interesting, I apologize. Woodward’s style is to leave his readers to their own devices, wandering through the corridors of power and eavesdropping on a few muttered conversations, often without context and certainly without analysis. No detail is too trivial to be recounted. A conversation never happens at the CIA headquarters but on the seventh floor of the CIA headquarters. US officials don’t fly around Afghanistan, they travel on “fixed-wing aircraft.” National security adviser Jim Jones doesn’t just take notes, he writes them into a “black Moleskine-style notebook.”

All this verite is to bolster Woodward’s credibility elsewhere. Since the multiple meetings that Woodward recounts are often top secret and sometimes occur in the White House’s situation room, the dialogues he provides are the recollections of one or more of the participants. How reliable they are we cannot possibly know, so Woodward is buttressing his mole’s account with Moleskine-style particularity.

Sometimes this mania for detail lapses into absurdity and the reader cannot see Woodward for the trees. So we find Bruce Riedel, a peripheral figure, about to get a phone call from the president: “Sprawled in his lap was his King Charles spaniel, Nelson, named after the celebrated British admiral.”

In fact, Admiral Nelson is the only non-American commander mentioned in Obama’s Wars, other than an Italian officer in Afghanistan (whose reward here is to be transcribed with comedy syntax). This is odd because Afghanistan is properly a NATO-led conflict and Britain has 9,500 troops there today.

Anything outside the Beltway, the ring road circling Washington DC, amounts to little. Just how little is expressed by Jim Jones, explaining the importance of the war to Woodward as they fly “in a giant C-17 cargo plane that can carry 160,000 pounds [73 tonnes]” to Afghanistan: “If we don’t succeed here, organizations like NATO, by association the European Union, and the United Nations might be relegated to the dustbin of history.” This ludicrous statement, made by one of Obama’s most senior advisers, is blankly received by Woodward, whose response is: “It sounded like a good case.”

The overall result is what American journalists call a “notebook dump,” with such unfiltered marginalia as Hillary Clinton replacing Joe Biden as vice president, Hamid Karzai casually diagnosed as manic depressive and the president of Pakistan fearing a US plot to destroy his country, all given equal respect.

No one can accuse Woodward of being lazy, even if his technique is formulaic. A formidable amount of work has gone into mining the memories of deputies and under-secretaries. Yet Woodward’s books on the Bush years worked better because his reliance on a few sources within a tight-lipped administration steered him towards a narrative — his sources’ narrative, but a narrative nonetheless. To avoid that fate the Obama administration took a deliberate decision that everyone should talk, and so deprived Woodward of being steered at the cost of exposing its in-fighting.

May 26 to June 1 When the Qing Dynasty first took control over many parts of Taiwan in 1684, it roughly continued the Kingdom of Tungning’s administrative borders (see below), setting up one prefecture and three counties. The actual area of control covered today’s Chiayi, Tainan and Kaohsiung. The administrative center was in Taiwan Prefecture, in today’s Tainan. But as Han settlement expanded and due to rebellions and other international incidents, the administrative units became more complex. By the time Taiwan became a province of the Qing in 1887, there were three prefectures, eleven counties, three subprefectures and one directly-administered prefecture, with

It’s an enormous dome of colorful glass, something between the Sistine Chapel and a Marc Chagall fresco. And yet, it’s just a subway station. Formosa Boulevard is the heart of Kaohsiung’s mass transit system. In metro terms, it’s modest: the only transfer station in a network with just two lines. But it’s a landmark nonetheless: a civic space that serves as much more than a point of transit. On a hot Sunday, the corridors and vast halls are filled with a market selling everything from second-hand clothes to toys and house decorations. It’s just one of the many events the station hosts,

Among Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) villages, a certain rivalry exists between Arunothai, the largest of these villages, and Mae Salong, which is currently the most prosperous. Historically, the rivalry stems from a split in KMT military factions in the early 1960s, which divided command and opium territories after Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) cut off open support in 1961 due to international pressure (see part two, “The KMT opium lords of the Golden Triangle,” on May 20). But today this rivalry manifests as a different kind of split, with Arunothai leading a pro-China faction and Mae Salong staunchly aligned to Taiwan.

Two moves show Taichung Mayor Lu Shiow-yen (盧秀燕) is gunning for Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) party chair and the 2028 presidential election. Technically, these are not yet “officially” official, but by the rules of Taiwan politics, she is now on the dance floor. Earlier this month Lu confirmed in an interview in Japan’s Nikkei that she was considering running for KMT chair. This is not new news, but according to reports from her camp she previously was still considering the case for and against running. By choosing a respected, international news outlet, she declared it to the world. While the outside world