“Can you read sheet music?” asks Katy Perry as we climb the stairs of a photo studio on Broadway.

“A little,” I say.

She stops and holds out the edges of her dress, patterned with a series of ascending quavers and semiquavers. “Then what song am I?” she asks, twirling.

“Three Blind Mice?”

“The Girl From Ipanema,” she says, before breaking into song. “I feel like I’m squeezed into a giant condom in this dress,” she adds.

Retro pop reference, modern twist, smutty punchline: I’m with the right Katy Perry, then. It’s a sweltering day in Manhattan — temperatures are in the 30s — but Perry, who arrived from Los Angeles a few days ago, isn’t complaining. “It’s good for my voice,” she says of the humidity, as a team of make-up artists and hair stylists buzz around, preparing for the shoot.

She concentrates on the mirror in front of her: Her eyes are huge, like an anime character’s, with lashes so thick you could use them to rake a lawn. She is wearing a platinum-blond wig; on her left hand is an engagement ring from Russell Brand, whom she met last year at the MTV music awards, an event at which she was lowered on to the stage atop a giant gold banana. (“I like fruit,” she shrugs.) With her Vargas girl looks and thrift store-bombshell aesthetic, the singer wouldn’t look out of place on the nose cone of a second world war B-17 bomber — or rather the nose cone of a B-17 bomber as painted by Roy Lichtenstein.

“I don’t feel like I’m very pop-star lame, but I’m definitely not hipster-cool,” she says. “I’m somewhere right in the middle of it all. Because, for me, I want to sell out, but just not in the ‘I’ve sold out’ kind of way. I want to sell out arenas and sell millions of records.”

The cover of her new album, Teenage Dream, features the singer semi-naked draped on a bed of pink tufty clouds. Perry had each cover individually spritzed to smell like candy floss. “It actually smells a bit like My Little Pony,” she says, a frown threatening to form. “You know, the toys?” The frown disappears. “So it smells of your childhood, which is always endearing.”

Perry is plenty endearing herself — unguarded, unpretentious, flirtatious in a slightly camp way. She swears like a sailor, rattling off the first thing that pops into her head, although her loose tongue has landed her in trouble in the past. When she described herself as a “fatter version of Amy Winehouse and a thinner version of Lily Allen,” Allen came out blasting, “It’s like, you’re not English and you don’t write your own songs, shut up!”

In fact, she writes her own lyrics; a producer helps flesh them out into songs. Teenage Dream features the already released single California Gurls, whose Velcro hook has probably already attached itself to the inside of your cranium, and a handful of love songs — Hummingbird Heartbeat, Not Like the Movies — inspired by Brand.

“One of the things that attracted me to him is his brain,” Perry says. “He’s one of the smartest men I’ve met. I feel smarter just standing next to him.” At the MTV music awards, she engineered an introduction by throwing a bottle of water at his head. He tried to get her into bed; she insisted on dinner, and a few weeks later they were on holiday together in Thailand. There’s been a rash of speculation about how she “tamed” the self-proclaimed “S&M Willy Wonka,” although such talk misses the fact that Brand is the reformed hell-raiser, 25-year-old Perry the pin-up for “gin-n-juice” hedonism. You wonder how that combination is going to work.

“He knows that I’m young and have friends and a social life, and he was attracted to me. Not, ‘Oh let’s find a version of myself in a female.’ Every once in a while I need to remind him of that and he listens. It’s all about communication. It’s not about taming, because that won’t last. Everyone gets saggy tits. Not everything stays perfect. We all start to slow down. I think he was ready for change. I mean, you just don’t have the stamina to be in bed with 80 different women a week when you’re 35 and trying to do good work.”

They met while she was recording her album — exactly halfway through the writing of the title track, which means the intriguingly personal verse-lyrics (“You think I’m pretty without my make-up on”) were written pre-Brand and the anonymous chorus (“You make me feel like a teenage dream”) post-Brand.

“It’s about that feeling that I think so many people relate to,” Perry says, “when they get to their 20s and 30s and remember being a teenager and putting all or nothing into a relationship, and usually getting hurt, but it was such an amazing feeling — so pure and lovely and raw.”

This unarguable truth — that there is something pure and lovely and raw about teenage emotions — is the driving force behind the Perry phenomenon; a success story that seems custom-made to make the heads of New Musical Express rock music paper readers explode like melons. For all the retro stylings, her lyrics are cut with just enough Jagged Little Pill realism to satisfy tween fans that they’re not just being fobbed off with fluff (“There’s a stranger in my bed/And a pounding in my head” she sings on Last Friday Night, a rousing anthem to binge-drinking). Beneath the puppies-and-peppermint cuteness lies an unsentimental take on the industry that sustains her.

“You have to bust your ass at this,” she says, “which is why you don’t find me getting shitfaced in bars that much. It’s so intense, it’s like you catch a rocket and you’re hanging on for dear life and you’re like, ‘Gooooooo!’ The second record I’m more buckled in because, God, how many times do you see people slump on their sophomore record? Nine out of 10. But I’m still working, like, 13-hour days, five, six days a week and singing on top of it. And knowing that there’s someone right behind me, ready to go, ready to push me down the stairs, just like in Showgirls.”

The middle child of three, her parents were both born-again Pentecostal ministers in southern California — Christian camp, Christian friends, no MTV, no radio — but press stories of a parental rift over Perry’s lyrics ignore the “born again” bit. Before they came to their faith, her parents were 60s scenesters, her mother briefly dating Jimi Hendrix. Her father took acid and hung out with Timothy Leary. “They’re kooky little critters,” she says. “Of course they’ll hear a song like Peacock, and there’s a little moan that comes out of them: ‘Ooooh, Katy.’ Or when they see a magazine cover, they’re like, ‘Put some clothes on.’ But we get along fabulously. There’s no disowning. They know that the best thing they can do is support and love me and pray for me and not judge me. That’s why you don’t see me having a breakdown. That’s why I’m not hooked on drugs.”

At 17, she started traveling back and forth to Nashville to record an album of Christian rock, but when her record company went bankrupt, she moved to Los Angeles to start again, this time getting as far as an actual record, with actual sleeve notes, before that deal, too, collapsed. Broke, she got a job in A&R at a small record label just outside Los Angeles.

“That was the most depressing moment of my hustle,” she recalls. “I was sitting there in a cubicle, with 25 other trying-to-make-it-some-failed-artists in a box listening to the worst music you’ve ever heard in your entire life. Having no money, writing bad checks, renting a car after two cars had been repossessed, trying to give people constructive criticism and hope, when really I wanted to jump out of the building or cut my ears off and say, ‘I can’t help you! I can’t catch a break. What am I gonna say to you? And you sing off tune.’”

By the time Capitol records fished out an old demo of hers from the slushpile, she was ready. “I was like, someone throw the ball. I will hit that home run. I knew I Kissed a Girl was going to have an impact. It was hooky for me. I couldn’t stop singing it.” Her innuendo-laden floor filler, released in 2008, topped the charts in 30 countries; while the album from which it was released, One of the Boys, went platinum, selling more than 7 million copies. Promoting the follow-up, Perry will soon leave for Malaysia, Singapore, then Australia, Japan. “My air miles are impeccable,” she says. The biggest challenge faced by her and Brand, these days, is scheduling. Though she was miffed to find her fiance beating her to the cover of Rolling Stone.

“I was like, ‘You bitch! I was working in America first!’” she says, faux outraged. “For his birthday invitation, I did an e-vite superimposing my face on his Rolling Stone cover. ‘Come to my birthday party.’”

What do her parents make of him?

“My mother’s in love with him. And my father, I think he sees a lot of himself in him.”

Perry and Brand have just bought a US$3 million home in Los Angeles and are looking for a place in New York. When I ask whether this onrush of domesticity is likely to have any influence on her music, she groans. “Everyone asks me that. You look at someone like Beyonce singing Single Ladies, when we all know she’s married. Some of it is just for entertainment.”

But you can’t stay singing about being a teenager forever.

“Oh, I will always be honest with my music,” she says. “The records are black boxes for me. Like if you want to know who I am, my views, my perspective, things I love, things I hate, my convictions, my anthems. I’ve never let people’s opinions affect the way I write.”

Worrying about the future is not really Perry’s style. She’s all about the now, and right now, she and her music are, as the lyric to California Gurls has it, “undeniable.”

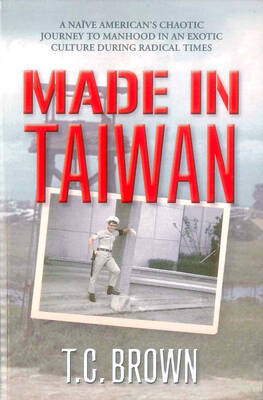

By 1971, heroin and opium use among US troops fighting in Vietnam had reached epidemic proportions, with 42 percent of American servicemen saying they’d tried opioids at least once and around 20 percent claiming some level of addiction, according to the US Department of Defense. Though heroin use by US troops has been little discussed in the context of Taiwan, these and other drugs — produced in part by rogue Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) armies then in Thailand and Myanmar — also spread to US military bases on the island, where soldiers were often stoned or high. American military policeman

Under pressure, President William Lai (賴清德) has enacted his first cabinet reshuffle. Whether it will be enough to staunch the bleeding remains to be seen. Cabinet members in the Executive Yuan almost always end up as sacrificial lambs, especially those appointed early in a president’s term. When presidents are under pressure, the cabinet is reshuffled. This is not unique to any party or president; this is the custom. This is the case in many democracies, especially parliamentary ones. In Taiwan, constitutionally the president presides over the heads of the five branches of government, each of which is confusingly translated as “president”

An attempt to promote friendship between Japan and countries in Africa has transformed into a xenophobic row about migration after inaccurate media reports suggested the scheme would lead to a “flood of immigrants.” The controversy erupted after the Japan International Cooperation Agency, or JICA, said this month it had designated four Japanese cities as “Africa hometowns” for partner countries in Africa: Mozambique, Nigeria, Ghana and Tanzania. The program, announced at the end of an international conference on African development in Yokohama, will involve personnel exchanges and events to foster closer ties between the four regional Japanese cities — Imabari, Kisarazu, Sanjo and

Sept. 1 to Sept. 7 In 1899, Kozaburo Hirai became the first documented Japanese to wed a Taiwanese under colonial rule. The soldier was partly motivated by the government’s policy of assimilating the Taiwanese population through intermarriage. While his friends and family disapproved and even mocked him, the marriage endured. By 1930, when his story appeared in Tales of Virtuous Deeds in Taiwan, Hirai had settled in his wife’s rural Changhua hometown, farming the land and integrating into local society. Similarly, Aiko Fujii, who married into the prominent Wufeng Lin Family (霧峰林家) in 1927, quickly learned Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) and