For those looking for the next spiritual leader of Tibet after the Dalai Lama, the ageing monk’s 75th birthday ceremony last week offered some clues.

Sat next to the Nobel laureate at the front of the stage was the imposing figure of Ogyen Trinley Dorje, the Karmapa, a thickset 26-year-old with the highest profile among a cast of young lamas who might fill the void that will one day be left.

Separated by two generations, the Dalai Lama and the Karmapa share a particular bond as Tibetan figureheads who both fled their homeland for an uncertain life in exile.

The Karmapa, who made the perilous journey in 1999, is now 26 — the same age as the Dalai Lama when he escaped in 1959 following a failed Tibetan uprising against Chinese rule.

“You could say he’s like a father figure to me. I look at him as my teacher and my guide,” the Karmapa said of the Dalai Lama during an interview the day before the celebrations on July 6.

Both monks live in Dharamshala, the northern Indian hill town that serves as the base of the Tibetan government-in-exile.

Built like a basketball player, the Karmapa is modern in his tastes. He has an iPod, plays video games and revealed an impressive knowledge of developments in the World Cup.

Throughout the interview, he spoke slowly and guardedly, clearly sensitive to his position as a “guest” in India and also wary of defining any role he might play in the future.

He said he tries not to think about the passing of the Dalai Lama, but admitted that his death would have a “huge impact” on the Tibetan movement and its struggle for genuine autonomy under Chinese rule.

There’s “no hurry” to think about succession, he said, before adding that he would “do my best to give a supporting hand to the activities that the Dalai Lama has carried on.”

“I would definitely look forward to leaving behind a rich legacy of service to Tibet and Tibetans in my own capacity,” he said.

As the Karmapa, he is one of Tibetan Buddhism’s most revered leaders, along with the Dalai Lama and the Panchen Lama.

But the Panchen Lama is now a weakened institution. The reincarnation named by the Dalai Lama disappeared aged 6 — abducted by the Chinese, say campaigners — and Beijing has named its own figure.

What makes the Karmapa such a potent figure is that he is formally recognized not only by the Dalai Lama but also by China, which, prior to his escape, had been politically grooming him as the highest reincarnate lama under its control.

That dual recognition accords him a legitimacy that Beijing would find it difficult to strip away retroactively.

For this reason, the fluent Chinese speaker is seen as a possible mediator between Beijing and the 200,000-strong Tibetan community in exile, but he says he is viewed with suspicion in Beijing.

“For my part, I have no thought on a future solution as such, but on the part of the Chinese they may have their own internal worries about me playing a political role,” he said.

Speaking in Tibetan through his interpreter, he added: “I feel myself that they should relax.”

The Karmapa’s escape from his homeland was every bit as daring as that of the Dalai Lama.

The then 14-year-old undertook the extremely grueling and hazardous trek across the Himalayas in the dead of winter, and was nearly caught on the China-Nepal border when his party stumbled across two army camps.

His decision to leave was largely motivated by fears that he would be co-opted as a puppet of the Chinese authorities.

“One of my major concerns was that when I turned 18, I might be given a position in the government hierarchy. And at that point I may have to go against His Holiness the Dalai Lama and the cause for Tibet,” he explained.

During the interview, he frequently sighed and joked about the “heavy questions” and at one point said he felt like a chapati, the Indian flatbread formed by squeezing dough between one’s hands.

His advisers had stressed before that no political questions should be asked, lest the answers upset the Indian authorities who are always anxious to avoid provoking China.

The existence of the Tibetan movement in India, which lobbies openly for autonomy or independence and denounces human rights abuses in Tibet, is a constant thorn in the side of relations between the two Asian superpowers.

The Karmapa is candid when speaking about the frustrations of his life in Dharamshala and he gives the impression of a young man chafing at the invisible hands holding him back. Him as chapati dough is an instructive image: He is a figure squeezed on both sides by India and China.

“We still have some, you know, problems,” he said in English.

One of the largest is the foreign travel restriction imposed by the Indian government, which prevents him meeting followers overseas. A planned trip to Europe was scuttled earlier this year.

“When I was in Tibet, I could not go to other countries,” he said. “Now I am here in India, a democratic country that has been very kind to Tibet, but I still have some problems, some restrictions.”

In the 11 years, he has traveled just once, to the US in 2008, a trip described by an aide as “very successful” that made him “very happy.”

He lives in Dharamshala only because he is barred from his monastery in Sikkim, a sensitive northeastern Indian state that borders China.

He has also expressed a desire to go to a regular university in India to study something either scientific, religious or environmental, his aide says, but the request has gone unanswered.

“In the 21st century, time is very precious,” the Karmapa says, hinting at his frustration.

In the Dalai Lama’s office, spokesman Tenzin Taklha stressed that the Karmapa is one of a number of young lamas who could assume leadership responsibilities after the death of the current Dalai Lama.

“He’s certainly one of the most important spiritual leaders. He’s a charismatic, promising leader with a large number of followers,” he said.

The community in exile is braced for a huge struggle with Beijing about the future leadership. China has already stated it intends to have the final say on any incarnation.

Talk about succession is met with characteristic levity by the man in office at the moment.

“If I don’t commit suicide then otherwise my body is very healthy, another 10 to 20 years I can manage, no problem ... maybe 30 years,” he joked in an interview with India’s NDTV channel on his birthday.

Following the shock complete failure of all the recall votes against Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers on July 26, pan-blue supporters and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) were giddy with victory. A notable exception was KMT Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫), who knew better. At a press conference on July 29, he bowed deeply in gratitude to the voters and said the recalls were “not about which party won or lost, but were a great victory for the Taiwanese voters.” The entire recall process was a disaster for both the KMT and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). The only bright spot for

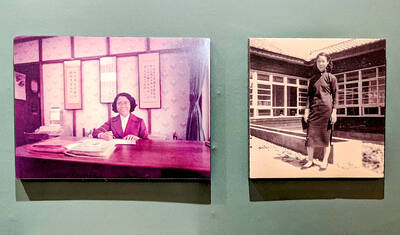

Aug. 11 to Aug. 17 Those who never heard of architect Hsiu Tse-lan (修澤蘭) must have seen her work — on the reverse of the NT$100 bill is the Yangmingshan Zhongshan Hall (陽明山中山樓). Then-president Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) reportedly hand-picked her for the job and gave her just 13 months to complete it in time for the centennial of Republic of China founder Sun Yat-sen’s birth on Nov. 12, 1966. Another landmark project is Garden City (花園新城) in New Taipei City’s Sindian District (新店) — Taiwan’s first mountainside planned community, which Hsiu initiated in 1968. She was involved in every stage, from selecting

Water management is one of the most powerful forces shaping modern Taiwan’s landscapes and politics. Many of Taiwan’s township and county boundaries are defined by watersheds. The current course of the mighty Jhuoshuei River (濁水溪) was largely established by Japanese embankment building during the 1918-1923 period. Taoyuan is dotted with ponds constructed by settlers from China during the Qing period. Countless local civic actions have been driven by opposition to water projects. Last week something like 2,600mm of rain fell on southern Taiwan in seven days, peaking at over 2,800mm in Duona (多納) in Kaohsiung’s Maolin District (茂林), according to

As last month dawned, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was in a good position. The recall campaigns had strong momentum, polling showed many Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers at risk of recall and even the KMT was bracing for losing seats while facing a tsunami of voter fraud investigations. Polling pointed to some of the recalls being a lock for victory. Though in most districts the majority was against recalling their lawmaker, among voters “definitely” planning to vote, there were double-digit margins in favor of recall in at least five districts, with three districts near or above 20 percent in