Tsai Ming-liang (蔡明亮) was busy checking his schedule, making phone calls and setting up appointments to promote his new film, Face (臉), at Tsai Lee Lu (蔡李陸咖啡商號), a cafe in Yonghe (永和), Taipei County, he opened with actor friends Lee Kang-sheng (李康生) and Lu Yi-ching (陸奕靜), when I arrived for our interview in the morning on the day of the movie’s premiere. Though apparently suffering heartburn caused by the rice ball he had eaten earlier, Tsai spoke earnestly about his cinematic output and his life, which seem to merge in and out of one another.

In 2004, Tsai received an invitation from the Louvre to make the first film under an initiative in which the museum aims to create a collection open to international directors. He was given unfettered access to the museum’s premises, including spaces that had never opened to the public, but his mother was dying of cancer and Tsai felt anxious and lost and thought of giving up on the project.

Tsai finished the script after his mother passed away. The resulting work is Face, a tribute to Francois Truffaut and the spirit of New Wave cinema, featuring Truffaut’s alter-ego Jean-Pierre Leaud and muses Jeanne Moreau, Nathalie Baye and Fanny Ardant, as well as Tsai regulars Lee, Lu and Chen Shiang-chyi (陳湘琪).

Taipei Times: When you were the little boy Antoine in Kuching, what your relationship with the city like? [Tsai, who was born in Kuching, Malaysia, in 1957 once said that he felt like he was the boy Antoine in Truffaut’s The 400 Blows.]

Tsai Ming-liang: I was living with my grandparents. They took me to the movies every evening after my friends went home. There were seven, eight cinemas in town, and several of them were within walking distance from where we lived. It was a time when Hong Kong films were being made on a weekly basis, and there were all kinds of movies to see.

I have a very distinct memory of those days. Movie theaters were fun. You had Indians selling peanuts and Malays who gave me candy.

I entered a lonely phase when I moved back in with my parents in fifth grade. My father [who ran a noodle stall in the city] had a farm in the suburbs [where we lived]. I felt like an outsider among my brothers. If I had a fight with one of them, they would all give me the silent treatment afterwards. So I spent a lot of time alone in my own space.

I didn’t fit in with my classmates,

either. Some of them didn’t like me and forbade the whole class from speaking with me. But I didn’t think much of it. That’s how I am — I have my own world and don’t care so much about the rest. Even now I often have similar experiences or find myself in similar situations.

I started to submit articles to newspapers in high school and became friends with editors who were a lot older than me and took good care of me. I felt my relationship with the city was different than it was for other people. I was always alone, looking for someone to meet, riding my bike to see an old poet. I would stay at the newspaper’s office or at radio stations until late or sleep at my friends’ or grandparents’ homes. Life was free.

That’s why I felt close to Antoine, who is alone most of the time, engaging in a dialogue with the city by himself and realizing how important it is to him when he is forced to leave the place. I have very strong feelings about the film because it tells part of my story, too.

TT: What Time Is It Over There? (你那邊幾點, 2001) and Face deal directly with the subject of death, and both were shot in Paris. Was that a coincidence?

TM: It feels like a coincidence, but at the same time it seems inevitable. People often say they dreamed of becoming a director, but I never did. It took me some time to realize that cinema for me is neither an escape nor a dream. It is not a job I do, either. The idea of making films that reflect my personal vision comes from the cinema of Truffaut, Rainer Werner Fassbinder or Yasujiro Ozu. Their works inspire you to make films about yourself.

When I reached a certain phase of my creative career, death became a topic I needed to address, too. Death is a funny thing because we all try to avoid dealing with it. Lee tries to run away when his father passes away [in What Time Is It Over There?], but he can’t. Chen does manage to run away to Paris, but she can’t escape facing death altogether. She meets an older Leaud [in a brief cameo] in a Paris graveyard. Growing old is part of death.

In Face, I feel that my relationship with cinema is more clearly pronounced. It is an important part of me, in the same way that everything you have experienced becomes a part of you.

I wanted to shoot the aging visage of Leaud and his encounter with Lee [in Face]. This indicates that Face has to do with the idea of the making of cinema, since [Leaud and Lee] are the subjects of two directors’ creations.

But creation inevitably blends into and is informed by life. The passing of my mother represented everything that is uncontrollable and unpredictable in life. And I chose to use actors’ faces to examine death, the most difficult subject that we prepare ourselves for until the day it arrives.

If you think about it, actors are the strangest people in the world. They go in and out of different lives, traveling between life and death.

(Tsai’s father died in 1992, Lee’s in 1997. Tsai once said What Time Is It Over There? was subsequently made to help them resolve their grief.)

TT: As a film buff, it was a pleasure for me to see Truffaut’s actors and yours gathered together to create a work.

TM: My favorite scene is the one where Lee and Leaud are seen alone on the set of the Salome film and take turns recalling the names of past cinematic masters. Every time people ask who my favorite directors are, I say that there are just too many of them. I speak of Truffaut because he is the spokesman of the auteur theory that brings the idea of creation and of the [director as] author to cinema. The authors of New Wave cinema point out that out of the 1,000 Westerns you’ve seen, you’ll only remember the ones made by John Ford. The idea is to use the medium with passion and respect in order to make it powerful.

But 50 years after the emergence of auteur theory, most people are still in the habit of using cinema as a form of entertainment, an escape from reality. My films are intertwined with real life, and I suffer a lot to express what I want to express. Part of the suffering comes from my knowing that most audiences are used to the same movie being duplicated again and again.

TT: Since the anxieties in your films are closely related to those you experience in real life, have you ever woken up one day and found yourself in one of your own movies?

TM: Quiet often actually [laughs]. I don’t like to make films that much, really [laughs]. But when the opportunity presents itself, you seize it and make a movie. But when you’re making it, it’s painful. I can’t make movies about things I don’t understand. Say you ask me to make a gangster movie. I’d probably end up making a film about the loneliness of an outlaw [laughs].

I often deal with existential loneliness, fear of loss or disease, and getting old, which are closely related to my life. I remember this one night when I woke up with pain from gout. I was thirsty and had to drag myself downstairs to get a glass of water. I felt sorry for myself — a well-known director who doesn’t have anyone to take care of him [laughs]. No, I was just kidding. Solitude is part of life, and I learn to live with it and enjoy it, like the young me.

TT: In Face, Hsiao-kang [Lee’s character] receives news of his mother’s death when Mathieu Amalric performs oral sex on him. Does this mean that you feel guilty about your homosexuality?

TM: I think everyone, gay or straight, has feelings [of guilt] when it comes to erotic desire and lust, which is not always pure pleasure and, to many people, including myself [laughs], is often frustrating.

The feeling of remorse shown on the face [of Lee] doesn’t come from sex but the fact that I left my mother. As a director and a person who longs for freedom, I needed to express myself, to pursue the spirit that Truffaut represents. I couldn’t always stay by her side.

My mother was in a lot of pain toward the end of her life. One night I wasn’t home. I was out selling tickets [for my film]. She asked me to come home, and told me I didn’t love her anymore. We rarely said the word “love” — almost never — in my family. When I went home I told her: “If I could choose, I would suffer for you. But I can’t. Trust in your Goddess of Mercy and tell her to take your pain away if she wants you to live.” She nodded and calmed down. But I got this wrenching pain in my thigh afterwards, as if I was experiencing my mother’s pain.

What I’m saying is that, as someone’s child, I have these deep feelings of guilt, and I chose to express them in that way [as presented in Face].

TT: What do you think your films would have been like if you had not meet Lee in 1991?

TM: We would have met for sure [laughs]. When I look back, many things seem to have been arranged as if by fate. I was looking for an actor for a television drama that I had to start shooting in a week. I spotted Lee on the street. At first, I kind of regretted my decision. He acted and spoke slowly. He was like a robot, and I was trying to push him to do things the way I wanted him to do them. But he said to me: “That’s just the way I am. I’m not gong to change.”

I listened and thought about my own preconceptions as to how actors should perform. I had experience in theater as an actor and knew how to create the right emotion at the right time. But real people aren’t like that. So when I became more confident [as a director], I began to encourage actors to just be themselves in front of the camera.

You see in many European films that the actors don’t express much emotion. They don’t deliver messages such as, “I’m angry, happy, nervous or in pain.” Like in Robert Bresson’s films, you can’t tell how his actors feel or what they’re thinking. You have to guess what’s on their mind. And that’s important because audiences have to participate in the work.

Taiwanese audiences are trained to see movies as entertainment in Taiwan Thunderbolt Fire (台灣霹靂火) style. They don’t change because the whole environment hasn’t changed that much. Staying the same is easy, but changing is not. The most important thing I want to do with my films is to change how people view cinema. The existence of my works will at the very least confuse audiences. They’ll scratch their heads and say, “His films are terrible, but how come he’s been able to make movies for 20 years — and he even made this one at the Louvre?” [laughs].

TT: You once said that commercialization destroys cinema as artistic expression.

TM: Oh, absolutely. It murders everything [laughs].

TT: What do you think about your film being added to the Louvre’s permanent collection?

TM: Cinema has an industry behind it and thus a market to consider, so it has to be close to the public. But if the existing value system is devoid of the cultivation of virtue and aesthetics, this money-driven mentality will become another kind of Iron Curtain that imprisons you.

When my films are put in the context of the Hollywood system, people question them. You’ll have a jury member at the Golden Horse Awards saying, “We don’t encourage personal expression,” or a film critic in Hong Kong complaining that Tsai Ming-liang is becoming more and more self-indulgent.

Bringing about change is difficult, unless our government is determined to give artistic films enough space to grow and provide the public with more opportunities to see these films. Giving away money to make movies and hoping they’ll sell is not enough. This kind of cultural undertaking takes not one but 10 years before it gets results.

The significance of a film entering the collection of the Louvre lies in our re-thinking of cinema as artistic expression. Maybe we should start looking for a new and more proper place for [artistic] cinema in today’s world. If my film is being shown in a museum, you won’t complain about my long, static shots, will you? [laughs].

TT: What’s your take on the future of cinema?

TM: You can’t stop the advance of technology. People always want to build the Tower of Babel, to break limits. But I feel that the decline of artistic cinema has a lot to do with the digitalization of the medium.

To artists, celluloid and digital are merely different tools. But younger generations of filmmakers use the Internet to read and study. This kind of reading is fragmented and not substantial in my view. If young directors are not sensitive to the environment they live in, they can develop a business, but never cinema.

I am fully aware of my environment. That’s why I want to change it. I go out to sell tickets to you — otherwise you will never go to the theater to see my films.

TT: So you will continue your undertaking to change people’s views on cinema?

TM: This morning I heard a Buddhist monk on television saying, “It’s okay if you don’t understand it now. You’ll probably understand it tomorrow or in 10 years. Just take your time.” It was like me talking to my audience [laughs].

Just the other day, a Taiwanese government official said to Henri Loyrette [the director of the Louvre], “It was very bold of you to choose Tsai. Even I don’t understand his movies.” Loyrette replied, “When Picasso first showed his paintings, people said they didn’t understand them. So he told them, ‘Learn to understand.’”

For years I have talked to people and given lectures. People are helping me now because they understand what I am trying to say.

See ‘Taipei Times,’ Oct. 2, Page 13, for a review of ‘Face.’

July 28 to Aug. 3 Former president Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) reportedly maintained a simple diet and preferred to drink warm water — but one indulgence he enjoyed was a banned drink: Coca-Cola. Although a Coca-Cola plant was built in Taiwan in 1957, It was only allowed to sell to the US military and other American agencies. However, Chiang’s aides recall procuring the soft drink at US military exchange stores, and there’s also records of the Presidential Office ordering in bulk from Hong Kong. By the 1960s, it wasn’t difficult for those with means or connections to obtain Coca-Cola from the

Taiwan is today going to participate in a world-first experiment in democracy. Twenty-four Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers will face a recall vote, with the results determining if they keep their jobs. Some recalls look safe for the incumbents, other lawmakers appear heading for a fall and many could go either way. Predictions on the outcome vary widely, which is unsurprising — this is the first time worldwide a mass recall has ever been attempted at the national level. Even meteorologists are unclear what will happen. As this paper reported, the interactions between tropical storms Francisco and Com-May could lead to

A couple of weeks ago the parties aligned with the People’s Republic of China (PRC), the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), voted in the legislature to eliminate the subsidy that enables Taiwan Power Co (Taipower) to keep up with its burgeoning debt, and instead pay for universal cash handouts worth NT$10,000. The subsidy would have been NT$100 billion, while the cash handout had a budget of NT$235 billion. The bill mandates that the cash payments must be completed by Oct. 31 of this year. The changes were part of the overall NT$545 billion budget approved

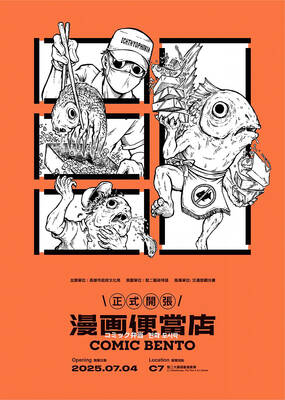

It looks like a restaurant — but it’s food for the mind. Kaohsiung’s Pier-2 Art Center is currently hosting Comic Bento (漫畫便當店), an immersive and quirky exhibition that spotlights Taiwanese comic and animation artists. The entire show is designed like a playful bento shop, where books, plushies and installations are laid out like food offerings — with a much deeper cultural bite. Visitors first enter what looks like a self-service restaurant. Comics, toys and merchandise are displayed buffet-style in trays typically used for lunch servings. Posters on the walls present each comic as a nutritional label for the stories and an ingredient