In late December 2007 a depressed, writer’s-blocked, pill-popping, opiate-addicted Marshall Mathers, better known as the multimilllion-album selling rapper Eminem, overdosed on some new blue pills someone gave him — they were methadone — and collapsed on his bathroom floor. Public statements covered up the reason for his emergency hospitalization and detox, claiming the problem was pneumonia. A month later Mathers had ramped up his habit again.

But the overdose scared him. Early last year he hospitalized himself, went through rehab and started the full 12-step program of a recovering addict, complete with meetings, a sponsor and a therapist. Mathers, 36, says he has stayed sober since April 20, 2008.

Far from concealing his addiction battle, he’s making it the center of his comeback. The cover of Relapse, the first new Eminem album since 2004, builds his face out of pills, and in some songs he raps, as directly as a rhymer can, about how drugs nearly destroyed him. Elsewhere on the album Eminem resumes — or relapses into — his main alter ego, Slim Shady: the sneering, clownish, paranoid, homophobic, celebrity-stalking compulsive rapist and serial killer who plays his exploits for queasy laughs and mass popularity.

Eminem’s four previous major-label albums of new material — The Slim Shady LP in 1999, The Marshall Mathers LP in 2000, The Eminem Show in 2002 and Encore in 2004 — have sold about 30 million copies in the US, according to Nielsen SoundScan. Relapse clings to the formula of its predecessors: it’s partly truth and partly fiction, with personal revelations and sociopathic farce side by side.

“It’s hard core, it’s dark comedy, it’s what Eminem has always been,” said Dr Dre, his longtime producer, by telephone from his studio in the San Fernando Valley of Southern California. Eminem had been missed; the album’s first single, Crack a Bottle — with 50 Cent and Dr Dre trading verses — went to No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 when it was released in February, selling 418,000 downloads in its first week.

Relapse is the latest episode in a soap-opera career that has always mingled confession, melodrama, comedy, horror, media baiting, craftsmanship and tabloid-scale hyperbole on every front.

“I don’t know if I’m exposing myself,” Mathers said by telephone from his studio in Detroit. “I’m kind of just coming clean and exhaling.”

He speaks amiably and coherently, without defensiveness, chatting with the zeal of a recovering addict about both his old excesses and his new clarity and productivity, sounding like someone relieved of a burden. “I was the worst kind of addict, a functioning addict,” he said. “I was so deep into my addiction at one point that I couldn’t picture myself being able to do anything without some kind of drug.”

He has been watching videos of himself on-stage and in interviews from his drug days, including one from Black Entertainment Television that he said he has no memory of doing, when Ambien made him so befuddled he couldn’t even respond to simple questions. “I want to see what I looked like when I was on drugs, so I never go back to it,” he said.

In the five years between his own albums, he worked as a producer, making beats for other rappers, and occasionally showed up as a guest rapper; he now calls his verse on Touch Down, with the Atlanta rapper T.I., “horrible.”

But last year, just two months out of rehab, Eminem met Dr Dre met in Orlando, Florida, to try recording. Eminem had been doing what he called “mind exercises” to get himself writing. “I’d stack a bunch of words and just go down the line and try to fill in the blanks and make sense out of them,” he said. “For three or four years I couldn’t do it any more.”

When he was sober, he said, “the wheels started turning again.” Working in Orlando and then in Detroit, Eminem and Dr Dre recorded hundreds of tracks and finished enough new songs for three albums. They have culled them to two; Eminem plans to release Relapse 2 before the end of this year. “The deeper I got into my addiction, the tighter the lid got on my creativity,” he said. “When I got sober the lid just came off. In seven months I accomplished more than I could accomplish in three or four years doing drugs.”

From the beginning, Mathers has smeared the boundary between Eminem and Slim Shady. In 97 Bonnie & Clyde from the 1999 Slim Shady LP, the rapper takes along his gurgly baby daughter — named Hailie, like Mathers’ real daughter (who lives with him in Detroit) — while disposing of her mother’s murdered corpse. The new album traces Eminem’s addictive tendencies to one of his earliest and most frequent targets: “My Mom,” who, the song says, used to mix Valium into his food to make him manageable.

But the music for songs like those is reassuring, even perky. Dr Dre has long provided clean, crisp tracks that are far from ominous. Often they have the bouncy beat and singsong choruses of kiddie music. That smiley-faced nastiness was enough to make Eminem a target for the censorious, which in turn gave him a new bunch of antagonists to provoke. “It ended up pushing my buttons,” he said. “You’re only going to make me worse now.”

Now, a decade into his major-label career, “I’m done explaining it,” he said. “Here’s my music. Here’s what it is. Get what you get from it. I didn’t get in this game to be a role model.”

Eminem was always an anomaly in hip-hop, not only because he’s white but also because he presents himself as multiple personas — rarely ingratiating, often belligerent or psychotic — rather than a single heroic face. Yet he was accepted within Detroit hip-hop, where he made his reputation in battle raps that were later depicted in the quasi-autobiographical 2002 movie 8 Mile. (The rapper Proof — his mentor, best friend and “ghetto pass,” as Eminem called him in his 2008 memoir, The Way I Am — was shot dead in 2006, and the grief was a factor in Eminem’s addiction.) And he was abetted by the leading hip-hop producer of the 1990s, Dr Dre, who also helped establish Snoop Dogg.

From the beginning Eminem was perfectly attuned to MTV: making videos full of snide pop-culture sendups and catchy pop hooks as well as news headlines with his marital and legal troubles. (Mathers has divorced, remarried and re-divorced Kim Scott. His mother, Debbie Mathers-Briggs, sued him in 1999 for defamation for US$10 million but later said it was her lawyer’s idea and settled out of court for US$25,000, most of it legal fees.)

As Slim Shady, in a tight white T-shirt with his hair bleached blonde, Eminem quickly became an offensive scourge to those who took Shady’s fantasies literally, or worried that others might; that made him a surly antihero to some fans. At the same time he was a pop pinup who made girls squeal. But he stayed in his hometown, Detroit, and never joined the celebrity culture.

Although he has a local hip-hop posse, D12, that he remained loyal to (and produced) when he grew famous, he hardly raps about friends or community; Eminem and Slim Shady are loners, estranged from virtually everyone. Relapse plays like the work of someone who’s been long isolated, seeing only his family, his pills and a TV; it’s not as funny as past albums.

Both Eminem and Dr Dre thought hard about how Eminem should re-emerge. And both concluded that the world wanted more Slim Shady. “I talked to my son about it,” said Dr Dre, “and he was like: ‘The kids want to hear him act the fool. We want to hear him be crazy, we want to hear him be Slim Shady and nothing else.’”

Relapse sets out to recapture the audience for his previous studio albums by presenting the familiar Eminem, which is to say, a ruckus of multiple personalities. “The album walks a fine line,” Mathers said. “My fans, and people who genuinely listen to hip-hop and love it for the art form, they know what’s Eminem, what’s Marshall and what’s Shady.”

On the album, Eminem is self-consciously autobiographical when he rhymes about himself — sometimes painfully frank, sometimes self-mocking. “Not only is honesty one of the biggest parts of recovery,” Mathers said. “I’m blessed enough to be able to have an outlet.”

The song Deja vu chronicles that night in December 2007 and the escalating drug habit that led up to it, with Eminem offering and then demolishing his old excuses; he rhymes “pneumonia” with “bologna.” In Beautiful, a grudgingly self-affirming song built on a power ballad, he wonders aloud whether he’ll ever rap again; he started writing it during the first day of one attempt at rehab, alone with a pen in a hospital room.

The album revisits Slim Shady’s usual obsessions so thoroughly that it sometimes threatens to become a rerun. It isn’t the first time he’s rapped about abducting women, or used the sound effect of duct tape peeling off the roll. Eminem once again mocks Christopher Reeve, who died in 2004; he has lines about slightly stale targets like Britney Spears, Lindsay Lohan, Kim Kardashian and Sarah Palin. “Once he makes a painting, once he lays a lyric down, it’s impossible to get him to change it,” Dr Dre said. “If there’s a couple of lines he says on a record that’s not relevant today, it’s, ‘No, that was that painting. That was for that moment.’”

After five years’ absence, Eminem still looms over hip-hop; the rapper Asher Roth devotes a song, As I Em, to complaining about being compared to Eminem because both are white. But We Made You, the second single from Relapse, had middling success on Top 40 radio; some references were dated. Dom Theodore, vice-president for Top 40 pop programming at CBS Radio, had mixed expectations for Relapse because Eminem’s hits had always been his humorous ones. “This album tends to be a little darker,” he said. “It’s still edgy, but not in a fun way. But I’d never write him off. You’d be hard pressed to find someone more talented.”

Despite his nine Grammy Awards, many MTV appearances and tens of millions of albums sold, Eminem hasn’t put himself on the celebrity circuit. “If it could just be about the music, I would only do the music,” he said. “I don’t hate the limelight, but I don’t like it.”

In the songs, Slim Shady still reacts to celebrities not like a fellow star but like a consumer stoking his crushes and fantasies from images on the airwaves. He just happens to be more extreme.

Confessions and broken taboos aren’t Eminem’s only concerns; he’s also a virtuoso of phonetics. His raps rhyme internal vowel sounds along with the syllables that end words, and he’ll let a chain of sounds take him wherever free-association might lead. “I’m taking celebrity names just out of the air, or just putting them in a hat and mixing them up and drawing a name,” he said. “If your name happens to rhyme with something good, then you might get it too.”

Word sounds are the genesis of Insane, a song on Relapse that accuses a stepfather of raping him as a child. “It’s pretty much all fiction,” he said. “It’s a perfect example of a rhyme gone bad.”

There are so many references to prescription drugs on Relapse that Eminem could have earned product-placement deals from pharmaceutical companies. One reason, he said, is that the trademarked names are memorable words. “In my experience through rehab and the hospital and the overdose with the methadone, I learned so many different names of medications,” he said.

“At the end of the day, it’s just words,” he added. “That’s all it is to me.”

But he also admits that he’s inseparable even from Slim Shady’s darker fantasies or, “obviously, I wouldn’t be able to think of this.” In one song, Must Be the Ganja — which rhymes “dilemma,” “Dalai Lama” and “Jeffrey Dahmer” — he boasts about being able to name “every serial killer who ever existed” in chronological order along with all the details of their murders. Mathers said that was him: watching documentaries and writing down information, “dates and times and places.” He was fascinated by “serial killers and their psyche and their mind states.”

He continued, “You listen to these people talk, or you see them, they look so regular. What does a serial killer look like? He don’t look like anything. He looks like you. You could be living next door to one. If I lived next door to you, you could be.”

Was that Slim, or Eminem, or Marshall?

“That was Marshall,” he said. “Uh-oh, I mean, that was Shady.”

May 26 to June 1 When the Qing Dynasty first took control over many parts of Taiwan in 1684, it roughly continued the Kingdom of Tungning’s administrative borders (see below), setting up one prefecture and three counties. The actual area of control covered today’s Chiayi, Tainan and Kaohsiung. The administrative center was in Taiwan Prefecture, in today’s Tainan. But as Han settlement expanded and due to rebellions and other international incidents, the administrative units became more complex. By the time Taiwan became a province of the Qing in 1887, there were three prefectures, eleven counties, three subprefectures and one directly-administered prefecture, with

President William Lai (賴清德) yesterday delivered an address marking the first anniversary of his presidency. In the speech, Lai affirmed Taiwan’s global role in technology, trade and security. He announced economic and national security initiatives, and emphasized democratic values and cross-party cooperation. The following is the full text of his speech: Yesterday, outside of Beida Elementary School in New Taipei City’s Sanxia District (三峽), there was a major traffic accident that, sadly, claimed several lives and resulted in multiple injuries. The Executive Yuan immediately formed a task force, and last night I personally visited the victims in hospital. Central government agencies and the

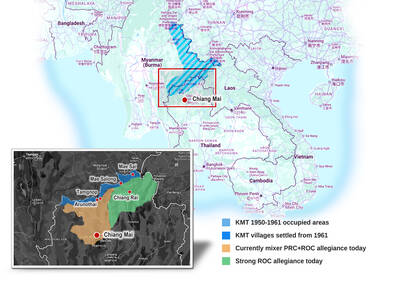

Among Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) villages, a certain rivalry exists between Arunothai, the largest of these villages, and Mae Salong, which is currently the most prosperous. Historically, the rivalry stems from a split in KMT military factions in the early 1960s, which divided command and opium territories after Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) cut off open support in 1961 due to international pressure (see part two, “The KMT opium lords of the Golden Triangle,” on May 20). But today this rivalry manifests as a different kind of split, with Arunothai leading a pro-China faction and Mae Salong staunchly aligned to Taiwan.

As with most of northern Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) settlements, the village of Arunothai was only given a Thai name once the Thai government began in the 1970s to assert control over the border region and initiate a decades-long process of political integration. The village’s original name, bestowed by its Yunnanese founders when they first settled the valley in the late 1960s, was a Chinese name, Dagudi (大谷地), which literally translates as “a place for threshing rice.” At that time, these village founders did not know how permanent their settlement would be. Most of Arunothai’s first generation were soldiers