The first time that Sara Campbell blacked out in the water, she was transported to a lush green field. It was summer, she says, and she was surrounded by gorgeous men whispering to her. “The interesting physiological aspect of a blackout,” she says, “is that your senses return one by one. Your hearing comes back first, and your sight last. So, in my meadow, I could hear people whispering to me, and as my sight came back, I was looking up at a blue sky; then suddenly I saw a boat, and water, and people around me, and I had a moment of complete disconnect. I was gone.” Seconds later she heard, “You’re safe, you can breathe.” The gorgeous men were her safety divers.

This isn’t the only time Campbell has been unconscious in the water. As one of the world’s best, most fearless, free divers, hazard comes with the job. It happened again earlier this month, as she attempted her most ambitious dive yet.

Competing at the Vertical Blue competition in the Bahamas, Campbell set a world record in the women’s constant weight discipline, diving down 96m with no oxygen and nothing to propel her except a mermaid-like monofin. The film of that dive is mesmeric: a tiny figure descending along a dropped rope, her safety divers dangling in the water above her as she moves through the green murk, plummeting into silence. Just watching her is enough to make you frantically draw breath — Campbell was underwater, altogether, for three minutes 36 seconds.

That dive was celebrated with a punch of the air, but the next one, five days later, wasn’t so successful. Campbell was determined to push herself to the round figure of 100m, and managed it, but as she reached the surface she lost consciousness. The result was disqualification, and a level of exhaustion she’d never experienced before. “I wasn’t even able to string a sentence together. I got cold sores around my mouth and I thought, my body is run down now. It’s not wise to put it through that again.”

It’s not easy to fathom why free divers put their bodies through such stress. Their sport involves doing something counter-intuitive — diving far away from any oxygen source. And the physical changes are significant. As soon as your face is immersed in water, your heart rate slows. Then comes peripheral vasoconstriction, in which blood is drawn from your arms and legs towards your body’s core organs. As you descend further, your lungs contract to the size of lemons, and on the ascent “the compression in the lungs is reversing. In the final stages of the dive, from 10m to the surface, the size of your lungs doubles.”

Forbes magazine once named it the second most dangerous sport in the world — after sky diving off buildings. Campbell, her 1.5m frame curled up on her boyfriend’s couch, denies this, although she admits free divers sometimes rupture their ear drums — “but that’s minor. You get a puncture in a piece of skin and it heals.” And there’s “a thing we call lung squeeze”, when someone dives too deep for their lungs to sustain the compression. “It might lead to a slight cough with a spot of blood, to handfuls of blood coming out of your lungs. It happened to a girl in the Bahamas, and she was diving again in three or four days.”

Although there have been deaths among people practicing “no limits” free diving (which involves being propelled much further underwater on a weighted sled), Campbell emphasizes that no one has ever died in any form of competition.

Four years ago, she had never even tried the sport — she was in her mid-30s, living in London, running her own PR agency, and feeling increasingly sad. She didn’t enjoy “the intense pressure to earn enough money each month to pay the bills,” and her sister had just had a baby. “I was incredibly unhappy about that. I think deep down I knew that she was very fulfilled in her life, and that I wasn’t.”

Campbell went on holiday to Dahab, in Egypt, “and the only way I can describe it is that someone opened a lid in my head and put a note inside, saying: ‘This is where you’re going to live.’” She had been teaching yoga and meditation for a year alongside her PR business, so she arranged to set up classes at one of the local hotels. “Within two weeks of moving there, I had rented a house with a camel. Bedouin kids shoved six kittens under my door, a puppy got thrown over the wall, and there I was, all of a sudden, living in the middle of this Bedouin village with a camel, six cats and a dog.”

She hadn’t even heard of free diving, but Dahab is a center for the sport, and soon some of her yoga clients, noticing how long she was able to hold her breath during meditation, suggested she try it. Her talent was immediately obvious. Less than a year after she started, she broke three world records in a single weekend. Then she won gold in the constant weight category at the world championships in Egypt. From nowhere, she was diving head-to-head with the brilliant Natalia Molchanova, an ex-Soviet fin swimmer who is, in Campbell’s words, “a consummate athlete.” The pair still jostle for dominance of the women’s sport.

Campbell has been nicknamed Mighty Mouse due to the strength of her diminutive body, and although doctors have established that she has a lung capacity 25 percent bigger than most people her size, this doesn’t account for her incredible aptitude. Many of the world’s best free divers spend hours every day in training, but when I ask Campbell whether she indulges in any of the more bizarre practices, she just laughs. “I don’t do technique training, strength training, I don’t do lactic-acid tolerance … For me, the sport is about the love of discovery. The numbers, the records themselves, are incidental.”

A group of physicians at a university in Italy have been studying Campbell among a group of free divers, and have established that “people are excelling in these areas as they get older. It’s not like tennis or football, where you have teenagers and people in their early 20s being the superstars. It’s people in their 30s. What the physicians are interested in is how our more advanced mental development and self-belief — and ability to control stress and set goals — affects us.”

Campbell’s next goal is to reach the 100m mark — without blacking out. At 37, she has gone from an unhappy life in London to making her living from the sport. “My initial motivation in free diving was just that it made me so happy. I realized you don’t have to go through therapy, or weeks of feeling crappy — I could just jump in the water and feel brilliant. Even more so than meditating in a yoga room, there are no distractions. You don’t have cars passing, or phones ringing, or people making a noise in the next room, or dogs barking. It’s utter silence.”

But doesn’t the water pressure hurt? No, she laughs. “It’s more like being rolled up in a duvet. It’s comforting — like a big hug.”

May 18 to May 24 Pastor Yang Hsu’s (楊煦) congregation was shocked upon seeing the land he chose to build his orphanage. It was surrounded by mountains on three sides, and the only way to access it was to cross a river by foot. The soil was poor due to runoff, and large rocks strewn across the plot prevented much from growing. In addition, there was no running water or electricity. But it was all Yang could afford. He and his Indigenous Atayal wife Lin Feng-ying (林鳳英) had already been caring for 24 orphans in their home, and they were in

President William Lai (賴清德) yesterday delivered an address marking the first anniversary of his presidency. In the speech, Lai affirmed Taiwan’s global role in technology, trade and security. He announced economic and national security initiatives, and emphasized democratic values and cross-party cooperation. The following is the full text of his speech: Yesterday, outside of Beida Elementary School in New Taipei City’s Sanxia District (三峽), there was a major traffic accident that, sadly, claimed several lives and resulted in multiple injuries. The Executive Yuan immediately formed a task force, and last night I personally visited the victims in hospital. Central government agencies and the

Australia’s ABC last week published a piece on the recall campaign. The article emphasized the divisions in Taiwanese society and blamed the recall for worsening them. It quotes a supporter of the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) as saying “I’m 43 years old, born and raised here, and I’ve never seen the country this divided in my entire life.” Apparently, as an adult, she slept through the post-election violence in 2000 and 2004 by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), the veiled coup threats by the military when Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) became president, the 2006 Red Shirt protests against him ginned up by

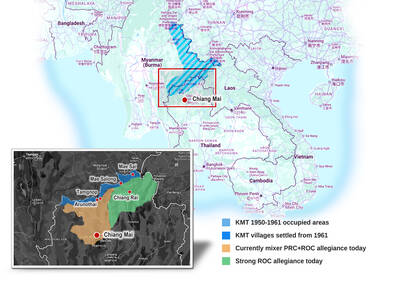

As with most of northern Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) settlements, the village of Arunothai was only given a Thai name once the Thai government began in the 1970s to assert control over the border region and initiate a decades-long process of political integration. The village’s original name, bestowed by its Yunnanese founders when they first settled the valley in the late 1960s, was a Chinese name, Dagudi (大谷地), which literally translates as “a place for threshing rice.” At that time, these village founders did not know how permanent their settlement would be. Most of Arunothai’s first generation were soldiers