Few masters in the history of modern Taiwanese art underwent the kind of dramatic aesthetic transformation experienced by Chu Teh-chun (朱德群). The stages of this transformation provide the framework for a retrospective that features more than 100 of his canvases, calligraphy and ink paintings and is currently on view at Taipei’s National Museum of History (國立歷史博物館).

The museum and the exhibit’s curators should be commended for producing one of the year’s most outstanding shows. From the arrangement of the paintings — mainly chronological but, somewhat mischievously, here and there disrupting the timeline so as to show contrast with his different artistic periods — to the explanation of the works themselves, the exhibit admirably reveals why Chu, 88, is regarded as one of Taiwan’s preeminent masters of abstract expressionism.

Chu’s early representational paintings of Taiwan’s rugged mountains and the expansive horizontal lines of its coasts greet viewers as they enter the exhibit. These seven formative canvases, which use broad brushstrokes and a liberal application of paint to capture the stark beauty and vibrant color of Taiwan’s natural scenery, are placed here as much as a testament to his early work as to show the remarkable contrast between these realistic landscapes and what was to come later.

Had Chu remained in Taiwan, he would probably be known as a proficient chronicler of Taiwan’s natural scenery, as these relatively small canvases show a painter in love with the graphic depiction of landscapes and seascapes, in works that are reminiscent of the style popularized by Canada’s Group of Seven.

The popularity of his first Taiwan solo exhibition in the early 1950s, however, convinced Chu to leave the island and further his studies in France. He never looked back, both in terms of where he chose to reside and his style of painting. The traditions of Chinese calligraphy and a love of landscapes that informed these earlier works, however, have remained constants throughout his long career.

As with many artists, a date can be assigned for when Chu had an epiphany that would change his style. In 1956 he visited a retrospective for abstract artist Nicolas de Stael at a museum in Paris and promptly abandoned representational painting. The geometric slabs of impasto color, which are hallmarks of De Stael’s abstract paintings, soon began to influence Chu’s work.

In one of the exhibit’s more ingenious flourishes, Fantasia (幻想曲), a post-Taiwan work done in 1958, and Seascape (海景), completed in 1954 just before Chu moved to France, are placed side-by-side. Rather than separating the two pictures or offering commentary, the museum allows the viewer to contemplate the differences between the layered color and horizontal brushstrokes of the latter and the sparse pigment and conservative use of oil with black vertical lines in the former.

Although De Stael remained a formative influence, it is clear during this early French period that Chu was also experimenting with a tradition outside the Western canon. The addition of stark black lines is evidence that Chinese calligraphy was becoming an important part of his visual vocabulary.

Another noticeable difference between these two works — differences that become more apparent with time — is the size of the canvas. Small canvases using copious amounts of paint mark Chu’s Taiwan period, which one museum official attributed to Chu’s poverty. Perhaps, but it also seems that the increasingly larger canvases are a hint that Chu was becoming more confident as an artist.

The works of Chu’s early French period, therefore, are not so much landscapes as they are experiments with the abstract-expressionist style popular in the West during this period, which served as a background to Chinese calligraphy brushstrokes that make up the foreground of these canvases.

The early 1960s saw Chu gradually moving away from De Stael’s geometric influences and finding a style all his own. In another sound decision by the curators, the exhibits’ explanations of the works spend little space analyzing Chu’s growing popularity. At the time Chu was receiving invitations to show his work at a number of international exhibitions, a situation that continues to the present day but one the curators chose not to belabor.

Having gained proficiency in abstract landscape painting, Chu began traveling the globe and applying his unique technique, which one might call “abstract expressionism with Chinese characteristics,” to paint some of the world’s most well-known natural sites. These landscapes comprise most of the rest of the exhibition, with each providing a clue to Chu’s feelings about the place. During this time Chu was studying Song Dynasty and Tang Dynasty poetry, which was beginning to influence on his aesthetic sensibility.

Of particular note are his series of paintings of the French Alps. On a trip across France in the mid 1980s, Chu saw the Alps in the distance and was immediately stuck by their timeless beauty.

The result: a series of large tempestuous canvases of fine white specks with flurries of brushstrokes imitating the flow of snow in winter. Black continues to be Chu’s color of choice to represent form, with twigs and trees practically jumping off the canvas.

Chu’s latter abstract period still employs the somber colors of his earlier abstract palette, but with the addition of pastel flourishes.

To help museumgoers gain a better understanding of Chu’s influences, the curators also display some of his cursive calligraphy and Chinese ink paintings, completing a splendid explication of the oeuvre of an abstract expressionist who combines a modern Western style with the aesthetic traditions of the East.

July 28 to Aug. 3 Former president Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) reportedly maintained a simple diet and preferred to drink warm water — but one indulgence he enjoyed was a banned drink: Coca-Cola. Although a Coca-Cola plant was built in Taiwan in 1957, It was only allowed to sell to the US military and other American agencies. However, Chiang’s aides recall procuring the soft drink at US military exchange stores, and there’s also records of the Presidential Office ordering in bulk from Hong Kong. By the 1960s, it wasn’t difficult for those with means or connections to obtain Coca-Cola from the

Taiwan is today going to participate in a world-first experiment in democracy. Twenty-four Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers will face a recall vote, with the results determining if they keep their jobs. Some recalls look safe for the incumbents, other lawmakers appear heading for a fall and many could go either way. Predictions on the outcome vary widely, which is unsurprising — this is the first time worldwide a mass recall has ever been attempted at the national level. Even meteorologists are unclear what will happen. As this paper reported, the interactions between tropical storms Francisco and Com-May could lead to

A couple of weeks ago the parties aligned with the People’s Republic of China (PRC), the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), voted in the legislature to eliminate the subsidy that enables Taiwan Power Co (Taipower) to keep up with its burgeoning debt, and instead pay for universal cash handouts worth NT$10,000. The subsidy would have been NT$100 billion, while the cash handout had a budget of NT$235 billion. The bill mandates that the cash payments must be completed by Oct. 31 of this year. The changes were part of the overall NT$545 billion budget approved

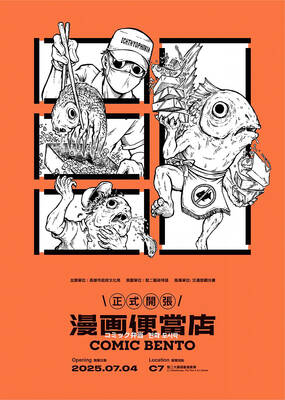

It looks like a restaurant — but it’s food for the mind. Kaohsiung’s Pier-2 Art Center is currently hosting Comic Bento (漫畫便當店), an immersive and quirky exhibition that spotlights Taiwanese comic and animation artists. The entire show is designed like a playful bento shop, where books, plushies and installations are laid out like food offerings — with a much deeper cultural bite. Visitors first enter what looks like a self-service restaurant. Comics, toys and merchandise are displayed buffet-style in trays typically used for lunch servings. Posters on the walls present each comic as a nutritional label for the stories and an ingredient