John Adams is working on a new piece, but he can’t describe it, he says, because it’s not going well. “Starting is always hell. Right now, I’m the most unpleasant person to be around: grumpy, uncommunicative, selfish. I have a vague idea of what I want it to be, but it’s just not working out. Worst of all, my wife won’t listen any more.”

Hearing Adams admit to self-doubt is something of a surprise. Now 61, the composer cemented his international reputation more than 20 years ago with Nixon in China, his opera about the former US president’s extraordinary meetings with Mao Zedong (毛澤東). Next week, Dr Atomic, his 2005 opera about the testing of the first atomic bomb, receives its New York premiere at the Metropolitan Opera. This month also sees the publication of Adams’ autobiography, Hallelujah Junction.

In music and in life, Adams chose a difficult route. From his early experimental compositions for homemade synthesizer to the minimalism of Grand Pianola Music (1982), from the chromatic Chamber Symphony (1994) to the Orientalism of his most recent opera, A Flowering Tree (2006), he has yet to settle into any kind of comfort zone. He arrived at Harvard in 1966 to study music, but knew he wanted to compose and abandoned his studies for a factory job in San Francisco. What was he running from? “I came of age,” he says, “when the operative model for a composer was a pseudo-scientist. If you read the early essays of [Pierre] Boulez and Milton Babbit, you’d get the impression music is all about finding the correct formula to suppress all individuality and emotion.”

But then, this was the 1960s; the tide of counterculture was rising fast, and while composers such as Babbit and Boulez were busy theorizing, the rest of the country was discovering the Beatles and John Coltrane. And LSD. Did Adams take acid? Yes, he says. Did it change the way he composed?

“It can certainly amplify and alter one’s perceptions,” he says. “The experience was powerful and amazing, and certainly changed the way I thought about things at the time. On the few occasions I was high, I did have these very powerful flashes of understanding about musical structure, and also about the usual holy-holy stuff. Although I wouldn’t say LSD changed the way I compose music, the culture of seeking mind-expanding experiences is something we miss now more than ever. The mindset of [US President] George [W.] Bush’s America is more closed than ever before. We’re all hunkered down, living in the shadow of our fears, most of them imaginary.”

It’s not hard to guess Adams’ politics. “We’re on the cusp of what could be real, reinvigorating change,” he says of the presidential election. “Or of sliding further into the repressive, reactionary, mind-numbing fear.” He believes that what he calls “contemporary serious music” has a role to play in changing mindsets; exactly what kind of a role became clear to him after Sept. 11. He was in London at the time, rehearsing for a film version of The Death of Klinghoffer, his controversial opera about the 1985 hijacking of a cruise ship by the Palestine Liberation Front.

He had also planned to attend a performance of one of his racier forays into minimalism, Short Ride in a Fast Machine (1986), at the Last Night of the Proms, but the program was changed in the wake of the attacks. Adams’ sparse, stately Tromba Lontana was performed instead, alongside Beethoven’s rousing Ninth Symphony.

“The resort to Beethoven, both in London and all over the world, made many of us painfully aware of a distressing reality,” he says. “Despite having created arguably the most vibrant musical culture of any country over the past half-century or so, there didn’t seem to be any American piece that could answer the country’s emotional needs at that time.”

The New York Philharmonic picked Adams as the man to plug the gap, and commissioned him to write a commemorative work for the first anniversary of the Sept. 11 attacks. Adams remains unhappy with the resulting work — a meditative choral piece, On the Transmigration of Souls. He feels the Republican administration manipulated the memory of the attacks, to create what he calls an “orgy of narcissism and collective victimization.”

Nor is he happy about the state of contemporary music. “We’re in danger of an overflow of extremely mediocre music,” he says, “partly because composing has become dangerously easy. Everyone can carry around software programs on a laptop and compose a new piece in a single evening. But the trouble is, of course, that the software dictates the parameters of what you can do, how you can think.”

So will there be no more Beethoven’s Ninth Symphonies or Mozart C Minor Masses? “I’ll certainly never be able to reach that level,” he says. “The great works of the past come about as a perfect collision of good fortune. You get a technology that just happens to have peaked at that time and a creative intelligence of just the right kind to exploit it. I’m not sure the Symphony Orchestra is going to see another Mahler, another Beethoven.”

Adams pauses, as if to reflect on whether he has just talked himself out of a job, then resumes. “But anyway, who the hell am I to talk like that? When I think of literature, everyone’s always said there’ll never be another Shakespeare, another George Eliot. But literature never ground to a halt. People go on writing truly great plays and novels. Maybe that’s what I’m doing, without even realizing it.”

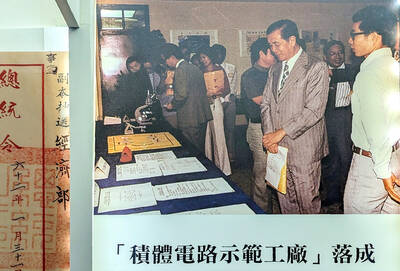

Oct. 27 to Nov. 2 Over a breakfast of soymilk and fried dough costing less than NT$400, seven officials and engineers agreed on a NT$400 million plan — unaware that it would mark the beginning of Taiwan’s semiconductor empire. It was a cold February morning in 1974. Gathered at the unassuming shop were Economics minister Sun Yun-hsuan (孫運璿), director-general of Transportation and Communications Kao Yu-shu (高玉樹), Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI) president Wang Chao-chen (王兆振), Telecommunications Laboratories director Kang Pao-huang (康寶煌), Executive Yuan secretary-general Fei Hua (費驊), director-general of Telecommunications Fang Hsien-chi (方賢齊) and Radio Corporation of America (RCA) Laboratories director Pan

The consensus on the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) chair race is that Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) ran a populist, ideological back-to-basics campaign and soundly defeated former Taipei mayor Hau Lung-bin (郝龍斌), the candidate backed by the big institutional players. Cheng tapped into a wave of popular enthusiasm within the KMT, while the institutional players’ get-out-the-vote abilities fell flat, suggesting their power has weakened significantly. Yet, a closer look at the race paints a more complicated picture, raising questions about some analysts’ conclusions, including my own. TURNOUT Here is a surprising statistic: Turnout was 130,678, or 39.46 percent of the 331,145 eligible party

The classic warmth of a good old-fashioned izakaya beckons you in, all cozy nooks and dark wood finishes, as tables order a third round and waiters sling tapas-sized bites and assorted — sometimes unidentifiable — skewered meats. But there’s a romantic hush about this Ximending (西門町) hotspot, with cocktails savored, plating elegant and never rushed and daters and diners lit by candlelight and chandelier. Each chair is mismatched and the assorted tables appear to be the fanciest picks from a nearby flea market. A naked sewing mannequin stands in a dimly lit corner, adorned with antique mirrors and draped foliage

The election of Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) as chair of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) marked a triumphant return of pride in the “Chinese” in the party name. Cheng wants Taiwanese to be proud to call themselves Chinese again. The unambiguous winner was a return to the KMT ideology that formed in the early 2000s under then chairman Lien Chan (連戰) and president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) put into practice as far as he could, until ultimately thwarted by hundreds of thousands of protestors thronging the streets in what became known as the Sunflower movement in 2014. Cheng is an unambiguous Chinese ethnonationalist,