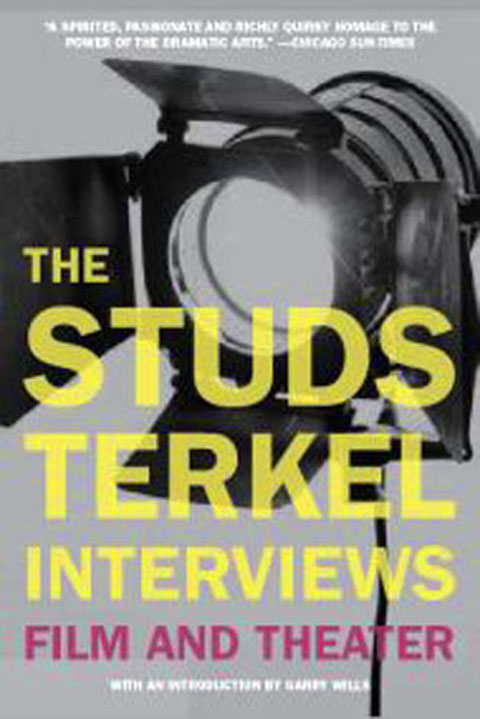

It can be hard to remember a time before pop and soccer celebrity, a time when an interview with someone famous wasn’t simply an opportunity to reveal reconstructive surgery on their septum or pose with newborn adopted babies from sub-Saharan Africa. But Studs Terkel belongs to a gentler age, an era when interviewers said things like: “What a tour de force that was. How did you carry that off?” and graciously kept quiet while their subjects rambled on about the creative subtleties of their art.

In his new collection of film and theater interviews, Terkel is so terribly polite, so scrupulously respectful, that I imagine he’s the kind of man who apologizes when he misses a shot at tennis. His opening gambit to actress Carol Channing when he meets her in 1959 is: “You have a sparkle and intelligence ...” She does not demur.

This old-fashioned gentility has served Terkel well. At 96, he is America’s preeminent oral historian, a man who has devoted his life to getting people to tell their stories. But his greatest strength is in conveying the experience of ordinary people, in getting them to elucidate the everyday grind of survival. His 1970 book, Hard Times, is deemed by many to be the quintessential oral history of the Great Depression. He has recorded interviews about work, war and race. In 1985, he won the Pulitzer Prize.

Terkel’s interview technique is self-deprecating and subtle — he removes himself from the foreground in order to allow his subject space to breathe. Reading a classic Terkel interview is a bit like looking at a pointillist painting: close up, it is merely a conglomeration of dots, but taken as a whole, a more arresting and cohesive picture forms itself. In his recent memoir, Touch and Go, Terkel attributes his success “[to] having celebrated the lives of the uncelebrated.”

The trouble with interviewing famous actors or directors is that they are already celebrated and, if allowed to, can wallow in pretension like hippos in pools of mud. While Terkel’s decision to let his interviewees speak for themselves (and never ask about their private lives) is an admirable one, the results in this collection can be hit and miss. Occasionally, as with the insufferably pompous Marlon Brando, it pays spectacular dividends. “Perhaps it is out of respect for what it means to be an artist that I do not call myself one,” says Brando, unaware that Terkel has handed him a long spool of rope with which to hang himself.

But it is a less fruitful technique when discussing the intricacies of a chorus-line folk dance in Oklahoma — unless, of course, you’re particularly enthused by that sort of thing.

When he hits his stride, however, Terkel elicits some fascinating insights into some of the greatest names of stage and screen, among them Tennessee Williams, Marcel Marceau, Ian McKellen and, um, Arnold Schwarzenegger. “When I was a small boy,” recalls the future governor of California, “my dream was not to be big physically, but big in a way that everybody listens to me when I talk, that I’m a very important person, that people recognize me and see me as something special. I had a big need for being singled out.”

The most perceptive and interesting passages come when Terkel is firmly on home ground. An extraordinary chapter deals with the varied audience reaction to some of the first performances of Waiting for Godot. When Alan Schneider directed the play in Miami, half of the well-heeled, white audience walked out. But when it was staged by a company of African-American actors in small Southern towns at the height of the civil-rights movement, the predominantly black audience felt an immediate and natural empathy for Beckett’s tramps. “Our audience knew a great deal about waiting,” recalls Gilbert Moses, the then director of Free Southern Theater. “They had been waiting all their lives [...] When Gogo takes off his shoe — a simple thing — and complains about its being too tight, the laughter of recognition bursts forth.”

The canonical shot of an East Asian city is a night skyline studded with towering apartment and office buildings, bright with neon and plastic signage, a landscape of energy and modernity. Another classic image is the same city seen from above, in which identical apartment towers march across the city, spilling out over nearby geography, like stylized soldiers colonizing new territory in a board game. Densely populated dynamic conurbations of money, technological innovation and convenience, it is hard to see the cities of East Asia as what they truly are: necropolises. Why is this? The East Asian development model, with

June 16 to June 22 The following flyer appeared on the streets of Hsinchu on June 12, 1895: “Taipei has already fallen to the Japanese barbarians, who have brought great misery to our land and people. We heard that the Japanese occupiers will tax our gardens, our houses, our bodies, and even our chickens, dogs, cows and pigs. They wear their hair wild, carve their teeth, tattoo their foreheads, wear strange clothes and speak a strange language. How can we be ruled by such people?” Posted by civilian militia leader Wu Tang-hsing (吳湯興), it was a call to arms to retake

This is a deeply unsettling period in Taiwan. Uncertainties are everywhere while everyone waits for a small army of other shoes to drop on nearly every front. During challenging times, interesting political changes can happen, yet all three major political parties are beset with scandals, strife and self-inflicted wounds. As the ruling party, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is held accountable for not only the challenges to the party, but also the nation. Taiwan is geopolitically and economically under threat. Domestically, the administration is under siege by the opposition-controlled legislature and growing discontent with what opponents characterize as arrogant, autocratic

When Lisa, 20, laces into her ultra-high heels for her shift at a strip club in Ukraine’s Kharkiv, she knows that aside from dancing, she will have to comfort traumatized soldiers. Since Russia’s 2022 invasion, exhausted troops are the main clientele of the Flash Dancers club in the center of the northeastern city, just 20 kilometers from Russian forces. For some customers, it provides an “escape” from the war, said Valerya Zavatska — a 25-year-old law graduate who runs the club with her mother, an ex-dancer. But many are not there just for the show. They “want to talk about what hurts,” she