Like countless others before him, Jonathan Willis rediscovered God in the solitude of a jail cell, 10 months after he’d been thrown into the Adams County lockup north of Denver to await trial for murder.

The blur of his crimes crystallized: The coke binge, the break-in, the brutal beating. Then desperation, arrest and, once in jail, the hell-raising that landed him in solitary.

“It went from dream to reality,” recalls Willis, 25. “When you reflect, with all the distraction cut away, you’re left with the core of life — what matters.”

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

He cried out to God, who answered with a challenge to get serious about his faith. He read the Bible, and the words spoke to him anew. His heart changed.

It was a classic jailhouse conversion.

“It’s natural to reach out to God in a period of duress,” said Michael Spotts, a volunteer assistant chaplain at the Adams County facility who witnessed the change in Willis. “The thing that tinges the jailhouse conversion with cynicism is that people like Jonathan killed someone. It’s inexcusable, horrible. But the genuineness of conversion can be found in absolute confession of what was done wrong, a seeking of repentance.”

Against the advice of his lawyer, Willis pled guilty, knowing that he was essentially sentencing himself to life without the possibility of parole.

His spiritual transformation began a chain reaction that already has touched others locked up around him. And, in a broader sense, it touched on a concept of faith-based rehabilitation that’s gaining traction as a burgeoning prison population now is going back into the community.

Bolstered by US President George W. Bush’s recent signing of the Second Chance Act, which promises more money for faith-based programs to help rehabilitate prisoners, corrections officials and religious volunteers are testing the largely unproven theory that faith can not only salvage criminals, but — in the long run — make the rest of us safer too.

Nearly 700,000 inmates return to the community each year nationwide.

Faith and prisons have been intertwined since the dawn of corrections, with criminal behavior often addressed as a moral issue. But church-and-state legal concerns temper the search for new faith-based ways to attack recidivism, which approaches 70 percent, according to one Department of Justice report.

In Colorado, a volunteer network of chaplains offers 216 programs and the Department of Corrections recognizes 36 faiths. Although those traditions range from Asatru, a polytheistic Norse religion, to Native American rituals to nature-based Wicca, the vast majority of volunteers represent Christian denominations.

Credible research on the effectiveness of faith-based programs remains sparse and inconclusive. But corrections experts and volunteers agree that such efforts, coupled with education, counseling and other therapies, could be part of the solution.

“I get asked all the time what’s the best predictor of success when somebody’s coming out of prison,” says Ari Zavaras, executive director of Colorado’s DOC. “Without question, if somebody had a true spiritual conversion — not the jailhouse kind that gets all the jokes, but the kind where they develop a spiritual base — I’d be almost able to bet a year’s pay without worry that they’re not going to re-offend.”

On a pleasant spring evening, about 70 offenders — roughly half the inmates at the minimum-security Camp George West in Golden — crowd a concrete-floored gymnasium to take in two hours of music, humor, feats of strength and Christian testimony.

Strongman and ex-con Mike Benson, who experienced his own jailhouse conversion, takes the stage and proceeds to tear a deck of cards in half, twist a horseshoe into an “S,” roll a frying pan into a burrito shape and snap a wooden baseball bat.

After breaking the bat, he briefly holds the two pieces before him to form a cross.

“Before I knew Jesus, this was malicious destruction of property,” jokes Benson. “Now, it’s ministry.”

Prison Fellowship Ministries, launched in 1976 by convicted Watergate conspirator Chuck Colson, claims more than 22,000 volunteers at 1,800 institutions with two intertwined roles: win souls and address crime through “restorative change” in offenders.

Mark Earley, a former Virginia attorney general and Republican candidate for governor in 2001, took the job leading the largest prison ministry shortly after his gubernatorial defeat.

“For almost 15 years, I thought the answer to public safety was to put as many people in prison as we can,” says Earley as he watches this presentation, called Operation Starting Line. “I was wrong. Crime is not a wedge issue anymore. Everybody realizes there’s not a lot more to do to get tough on crime. The sweet spot is helping them be different when they come out.”

Prison Fellowship offers several programs, mostly intermittent volunteer efforts like Bible study and seminars. But the organization swung for the fences with its InnerChange Freedom Initiative, an intensive Bible-based program that starts within a prison but then extends beyond the walls when an inmate gets paroled.

Early analysis of the program — a public-private partnership — showed some promise in reducing recidivism.

Jonathan Willis, now serving a life sentence, awakens each morning in the high-security Limon Correctional Facility in eastern Colorado, where he attends weekly worship and daily Bible studies as he integrates into the prison population.

He also continues to work toward reconciliation with his victim’s family — a priority he couldn’t accomplish, he says, if he’d let his case go to trial.

“There’s no way I could say I’m sorry to this family,” he says, “and then try to escape the consequences.”

As Willis thinks about spending the rest of his life in prison, he notes that his spiritual rebirth gave him something he never had on the outside — a purpose. He wants to transform other prisoners who one day will see life on the outside.

May 26 to June 1 When the Qing Dynasty first took control over many parts of Taiwan in 1684, it roughly continued the Kingdom of Tungning’s administrative borders (see below), setting up one prefecture and three counties. The actual area of control covered today’s Chiayi, Tainan and Kaohsiung. The administrative center was in Taiwan Prefecture, in today’s Tainan. But as Han settlement expanded and due to rebellions and other international incidents, the administrative units became more complex. By the time Taiwan became a province of the Qing in 1887, there were three prefectures, eleven counties, three subprefectures and one directly-administered prefecture, with

President William Lai (賴清德) yesterday delivered an address marking the first anniversary of his presidency. In the speech, Lai affirmed Taiwan’s global role in technology, trade and security. He announced economic and national security initiatives, and emphasized democratic values and cross-party cooperation. The following is the full text of his speech: Yesterday, outside of Beida Elementary School in New Taipei City’s Sanxia District (三峽), there was a major traffic accident that, sadly, claimed several lives and resulted in multiple injuries. The Executive Yuan immediately formed a task force, and last night I personally visited the victims in hospital. Central government agencies and the

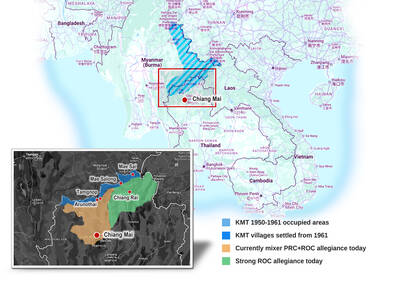

Among Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) villages, a certain rivalry exists between Arunothai, the largest of these villages, and Mae Salong, which is currently the most prosperous. Historically, the rivalry stems from a split in KMT military factions in the early 1960s, which divided command and opium territories after Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) cut off open support in 1961 due to international pressure (see part two, “The KMT opium lords of the Golden Triangle,” on May 20). But today this rivalry manifests as a different kind of split, with Arunothai leading a pro-China faction and Mae Salong staunchly aligned to Taiwan.

As with most of northern Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) settlements, the village of Arunothai was only given a Thai name once the Thai government began in the 1970s to assert control over the border region and initiate a decades-long process of political integration. The village’s original name, bestowed by its Yunnanese founders when they first settled the valley in the late 1960s, was a Chinese name, Dagudi (大谷地), which literally translates as “a place for threshing rice.” At that time, these village founders did not know how permanent their settlement would be. Most of Arunothai’s first generation were soldiers