On a train bound from Warsaw to Belgrade, Colonel Jean-Francois Mercier, the immensely attractive hero of Alan Furst’s sinuous new novel, cannot decide what to read. Should it be Stendhal’s Red and the Black, which a teacher once told him was “a political novel, very nearly a spy novel, one of the first ever written”? Or should it be The Bar on the Seine, an early Georges Simenon detective story featuring Commissaire Jules Maigret?

One is a much-admired classic, the other a more forthright page-turner. Mercier winds up devouring both. And no wonder: Furst’s instant espionage classics are equally indebted to both kinds of fiction. His stories combine keen deductive precision with much deeper, more turbulent and impassioned aspects of character. Since they are also soigne and steamy, there is the inevitable woman in the dining car, with whom Mercier will have this perfectly succinct conversation:

“‘So,’ she said, ‘an adventure on a train.’

“‘No,’ he said. ‘More.’”

And, two pages and one change of venue later, in Mercier’s sleeping car: “They paused, shared a look of exquisite complicity, and she raised her hips.” This is one of those Furst one-sentence erotic marvels that truly could stop a train in its tracks.

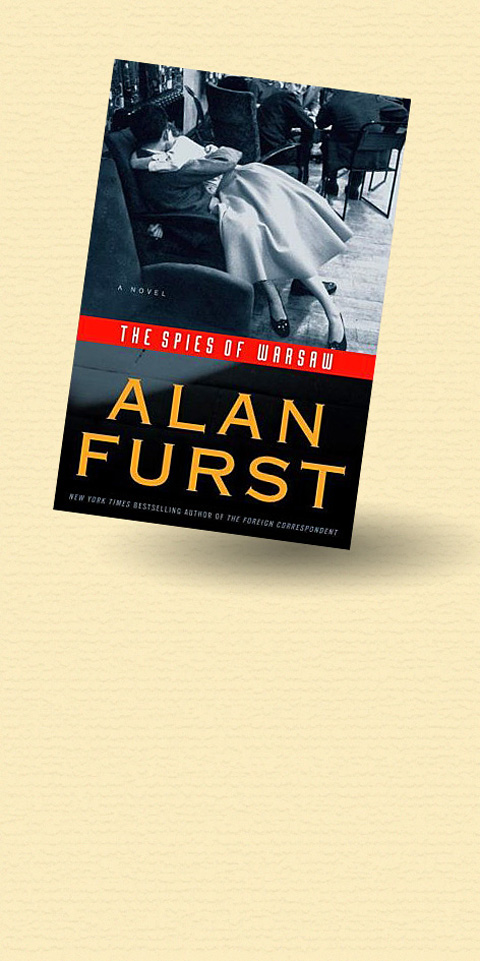

If Furst wrote arid, mechanical spy books, such steam heat might be surprising. But he can invest even the most humdrum situation with similarly elegant acuity. In this latest brooding, sophisticated period piece, The Spies of Warsaw, winter does not simply arrive. Instead, “out in the countryside, the first paw prints of wolves were seen near the villages.” It is late 1937 in Poland, and the atmosphere is charged with peril. The wolves are both metaphorical and real.

Mercier is a French aristocrat, a contemporary of Charles de Gaulle who, after lengthy military service, has become the military attache to Poland. France and Poland are allies, and Furst observes with characteristic worldliness, that “allies were, for reasons of the heart more than the brain, supposed to trust each other.”

But as Mercier acknowledges to his Polish counterpart, Colonel Anton Vyborg (“tall and well-built and thin-lipped, with webbed lines at the corners of eyes made to squint into blizzards”), the reality is different. With a second World War looming before military men old enough to have fought in the first one, Mercier says: “You know what I think, Anton. If the worst happens, and it starts again, you must be prepared to stand alone.”

As Furst has acknowledged, the outcomes of his pre-World War II novels are never in doubt. And much of the plot of The Spies of Warsaw hinges on a question answerable in hindsight: Yes, Germany will invade France. But this book is set at a point when a knowledge of Germany’s precise plans is all-important. And so, as the book begins, Mercier meets not only with fellow dignitaries but also with a character whom he holds in slight contempt.

Mercier is cultivating Edvard Uhl, a German who can provide the particulars about how German tanks are constructed. Uhl does this gladly because his monthly trips to Warsaw allow him to conduct an affair with a woman he thinks is royalty. But the woman is deceiving him. “I rather like her, actually,” the female spy says of the countess she impersonates when Uhl comes to town.

When Uhl arouses German suspicions, Mercier starts trying to protect him. And when questions of tank traps and fortifications arise, Mercier abandons any complaints about being bored by his work. As Furst plays his usual cat-and-mouse games, he lures both Mercier and the reader into high-stakes espionage activities in which prescience about a possible tank attack is all-important. To the extent that The Spies of Warsaw has a central thread, this is it.

Furst has created this book on a broad canvas. And he succeeds in doing so without losing sight of his narrative focus. Mercier deals with an arch, international mixture of characters, all of whom share a kind of anxiety that is anything but dated. “A bad dream,” Vyborg says about tank information found in Wehrmacht journals. “They write books and articles about what they intend to do, but nobody seems to notice, or care.”

As always, but with especially great efficacy in The Spies of Warsaw, Furst asks how life can go on in the face of encroaching menace. And in the book’s uncommonly fine-tuned portrait of Mercier, it has some kind of answer.

Following the shock complete failure of all the recall votes against Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers on July 26, pan-blue supporters and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) were giddy with victory. A notable exception was KMT Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫), who knew better. At a press conference on July 29, he bowed deeply in gratitude to the voters and said the recalls were “not about which party won or lost, but were a great victory for the Taiwanese voters.” The entire recall process was a disaster for both the KMT and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). The only bright spot for

Last week, on the heels of the recall election that turned out so badly for Taiwan, came the news that US President Donald Trump had blocked the transit of President William Lai (賴清德) through the US on his way to Latin America. A few days later the international media reported that in June a scheduled visit by Minister of National Defense Wellington Koo (顧立雄) for high level meetings was canceled by the US after China’s President Xi Jinping (習近平) asked Trump to curb US engagement with Taiwan during a June phone call. The cancellation of Lai’s transit was a gaudy

As last month dawned, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was in a good position. The recall campaigns had strong momentum, polling showed many Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers at risk of recall and even the KMT was bracing for losing seats while facing a tsunami of voter fraud investigations. Polling pointed to some of the recalls being a lock for victory. Though in most districts the majority was against recalling their lawmaker, among voters “definitely” planning to vote, there were double-digit margins in favor of recall in at least five districts, with three districts near or above 20 percent in

From Godzilla’s fiery atomic breath to post-apocalyptic anime and harrowing depictions of radiation sickness, the influence of the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki runs deep in Japanese popular culture. In the 80 years since the World War II attacks, stories of destruction and mutation have been fused with fears around natural disasters and, more recently, the Fukushima crisis. Classic manga and anime series Astro Boy is called “Mighty Atom” in Japanese, while city-leveling explosions loom large in other titles such as Akira, Neon Genesis Evangelion and Attack on Titan. “Living through tremendous pain” and overcoming trauma is a recurrent theme in Japan’s