For the past one and a half years, Manfred Schlaupitz, 71, a former Daimler-Benz engineer, has been living in the northern Thai province of Chiang Mai in a Swiss-run facility for senior citizens suffering from dementia.

Schlaupitz has Alzheimer’s. His wife, Hilde, asserts that her husband “has never been as relaxed as here since the onset of his condition.”

Over the past few years, Thailand has steadily gained in popularity for elderly Westerners to retire. The number of registered Germans around Chiang Mai, for example, has increased from 600 to 1,000 within the past eight years.

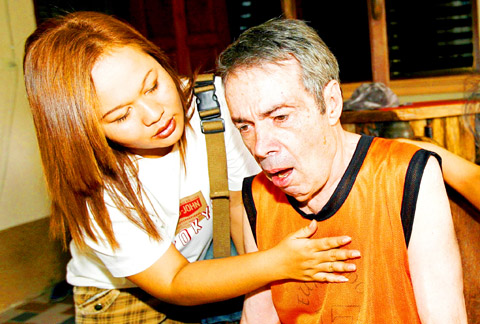

PHOTO: EPA

Retirement homes boasting every comfort have sprung up, and there even is one facility for gay retirees.

Swiss national Martin Woodtli’s facility consists of six houses distributed throughout the village of Faham in which his nine “long-term guests” reside. He never uses the term “patients.”

“In Europe, an Alzheimer’s diagnosis is like a rubber stamp imprinted on someone’s forehead that says, ‘This person is sick,’ but here, people tend to treat fellow humans who are different in a much more relaxed manner,” Woodtli says.

Schlaupitz’s dementia started when he was 63 years old. His wife was appalled by the nursing facilities she encountered back home: “substandard service and not enough staff.”

Woodtli’s Baan Kamlangchay to her seemed like a revelation.

Today, her husband shares one of the houses with another guest. Three female caregivers look after him exclusively 24 hours a day.

In Western nursing homes, accidents often occur when guests need to get up at night and fall. Not in Baan Kamlangchay. The night nurse sleeps in the same room as Schlaupitz and can assist him immediately should he need to get out of bed.

Schlaupitz’s main caregiver, Nui, discovered that Schlaupitz can be reached with music. He likes to whistle Jingle Bells, often in duet with Nui.

Counting is another way to interact with Schlaupitz. He can still count to 30, and Nui patiently plays the “number game” with him — in German — for hours on end.

“Our carers know the key words in German,” Woodtli says, “but language skills are really secondary. What counts much more is non-verbal communication.”

Sometimes Schlaupitz becomes restless. He changes chairs every few seconds, puts on his shoes, then takes them off, but Nui is by his side. He would not have a caregiver close by at all times in a nursing facility in Europe.

Still, it is not an easy decision for families to move their loved ones to faraway Thailand. “The nursing costs are playing an important role, of course,” Woodtli says.

Living in a nursing facility in Switzerland can easily cost US$7,570 dollars a month. Thanks to Thailand’s lower wages and living expenses, the cost here is less than half that.

But the attitude of Thais toward older people is even more important than financial concerns, Woodtli says.

“Thai people are very considerate towards the elderly,” he said. “For them, it almost is a sacred duty to care for old people.”

Unlike in Europe, Thais are not shy about the idea of touching an older person’s body and have no issues with spontaneously administering a facial, body massage or pedicure.

Woodtli got his idea to offer holidays and long-term stays for dementia patients after his experiences with his own mother, herself suffering from the illness.

“I couldn’t nurse her myself anymore, but nursing homes in Switzerland were simply inadequate,” he says.

Because he knew Thailand from previous working visits, he decided in 2002 to resettle there with his mother.

“Within weeks, she blossomed,” he remembers. His mother died in Chiang Mai in 2006.

Hilde Schlaupitz just visited her husband for four weeks, like the relatives of the other patients who often come three or even four times a year to look after their loved ones. Every house has at least one guest room to accommodate visitors.

Back home, Hilde Schlaupitz initially had to put up with skeptical and malicious comments over her decision to send her husband to Thailand. Doctors warned about the tropical climate, the new surroundings, even the long flight that might harm her husband.

The comments from friends and relatives that she simply wanted to get rid of her husband hurt her deeply.

So one day, she took her best friend with her to visit her husband in Chiang Mai. The friend was thrilled, which reassured Hilde Schlaupitz. She does not care about the gossip anymore.

“When I witness the loving care my husband receives here, and when I see how he is blossoming, I am 100 percent certain that staying here is the best that could happen to him,” she says.

“Here, Manfred can live in freedom and with dignity,” she adds.

April 28 to May 4 During the Japanese colonial era, a city’s “first” high school typically served Japanese students, while Taiwanese attended the “second” high school. Only in Taichung was this reversed. That’s because when Taichung First High School opened its doors on May 1, 1915 to serve Taiwanese students who were previously barred from secondary education, it was the only high school in town. Former principal Hideo Azukisawa threatened to quit when the government in 1922 attempted to transfer the “first” designation to a new local high school for Japanese students, leading to this unusual situation. Prior to the Taichung First

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) hatched a bold plan to charge forward and seize the initiative when he held a protest in front of the Taipei City Prosecutors’ Office. Though risky, because illegal, its success would help tackle at least six problems facing both himself and the KMT. What he did not see coming was Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (將萬安) tripping him up out of the gate. In spite of Chu being the most consequential and successful KMT chairman since the early 2010s — arguably saving the party from financial ruin and restoring its electoral viability —

The Ministry of Education last month proposed a nationwide ban on mobile devices in schools, aiming to curb concerns over student phone addiction. Under the revised regulation, which will take effect in August, teachers and schools will be required to collect mobile devices — including phones, laptops and wearables devices — for safekeeping during school hours, unless they are being used for educational purposes. For Chang Fong-ching (張鳳琴), the ban will have a positive impact. “It’s a good move,” says the professor in the department of

Toward the outside edge of Taichung City, in Wufeng District (霧峰去), sits a sprawling collection of single-story buildings with tiled roofs belonging to the Wufeng Lin (霧峰林家) family, who rose to prominence through success in military, commercial, and artistic endeavors in the 19th century. Most of these buildings have brick walls and tiled roofs in the traditional reddish-brown color, but in the middle is one incongruous property with bright white walls and a black tiled roof: Yipu Garden (頤圃). Purists may scoff at the Japanese-style exterior and its radical departure from the Fujianese architectural style of the surrounding buildings. However, the property