In the film Pleasantville (1998) the staid world of a black-and-white 1950s town is upended by the introduction of color. Something similar is happening at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan.

In the upper section of the lobby, a floor created by the artist Jim Lambie surrounds Auguste Rodin's sculpture of Balzac with concentric strips of brightly hued tape. Up on the sixth floor, a painted-aluminum construction by Donald Judd gives a lift to the gray towers visible through the skylight. Cheerful striped vests, designed by Daniel Buren, peek out from the regulation charcoal jackets of the museum guards.

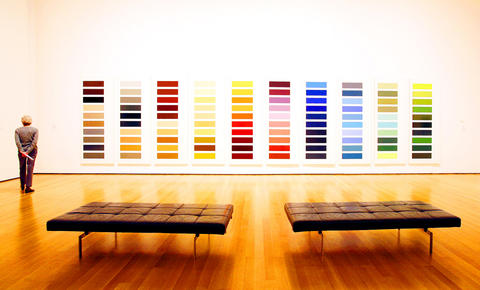

These and other interventions are part of Color Chart: Reinventing Color, 1950 to Today, which opened at the museum on Sunday. Organized by Ann Temkin, a curator in the museum's department of painting and sculpture, Color Chart looks at contemporary artists for whom color functions as a ready-made - something to be bought or appropriated, rather than mixed on a palette. As Frank Stella famously quipped, "I tried to keep the paint as good as it was in the can."

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

The show is a rejoinder to the notion of color as the province of formalists, and to the idea that Minimal and Conceptual art comes only in shades of black, white and gray. That Color Chart coincides with Jasper Johns: Gray at the Metropolitan Museum is a happy accident; in that show the pairing of Johns' red, yellow and blue painting False Start and its neutral counterpart Jubilee amounts to a Pleasantville experience in reverse.

Temkin's thesis owes much to the British artist and writer David Batchelor, whose book Chromophobia (2000) is a thorough and witty cultural history of color, including in its thematic discussions Heart of Darkness and the movie version of The Wizard of Oz. Regrettably, photographs from Batchelor's series Found Monochromes of London, a visual diary of white rectangles glimpsed during his daily travels, have been tucked away near the museum's sixth-floor bathrooms.

As Batchelor writes: "The color chart divorces color from conventional theory and turns every color into a ready-made. It promises autonomy for color; in fact, it offers three distinct but related types of autonomy: that of each color from every other color, that of color from the dictates of color theory and that of color from the register of representation." In other words, we are far from Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's Theory of Colors and from the deceptive relationships of Josef Albers' homages to the square.

This show's first gallery makes the novelty of autonomous color gloriously apparent. A series of signature works by Ellsworth Kelly, from 1951, shows him experimenting with randomly generated patterns of squares cut from store-bought colored paper. One of these collages gave rise to the contemporary masterpiece Colors for a Large Wall, a stunning, nearly 2.4m2 grid composed of 64 separate canvases.

Kelly may be an obvious choice, as are Yves Klein, Andy Warhol and Stella, but the inclusion of Robert Rauschenberg's Rebus (1955) offers a fresh angle on an artist whose color choices are rarely, if ever, analyzed. One of his early "combine" paintings, it includes a horizontal spectrum of cardboard paint samples. More to the point, it contains splashes of colors purchased in unlabeled cans from surplus stock on the Bowery.

In one of many fascinating anecdotes in the exhibition catalog, Rauschenberg recalls: "It was like 10 cents for a quart can downtown, because nobody knew what color it was. I would just go and buy a whole mess of paint, and the only organization, choice or discipline was that I had to use some or all of it, and I wouldn't buy any more paint until I'd used that up."

As subsequent galleries reveal, European artists under the spell of Rauschenberg and John Cage developed their own strategies for liberating color from aesthetic intent. An entire wall is devoted to Gerhard Richter's Ten Large Color Panels (1966-1972), a 9.4m sequence that elevates hardware-store paint chips to monumental proportions.

Many of the show's artists look to the automobile industry for an explicitly commercial palette, one best captured by the Tom Wolfe essay The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby. Color Chart includes John Chamberlain's suite of album-size paintings, made with car lacquer on Masonite and Formica; Alighiero Boetti's monochromes made in Turin, Italy, with Fiat motorcycle enamel; and Jan Dibbets' photographs of car hoods.

Color Chart suffers, in places, from the visual redundancy of its many chart-based works. Strained viewers can rest their eyes on Lawrence Weiner's wall text invoking permutations of red, green and blue, or Sol LeWitt's ethereal wall drawing composed of thin lines of colored pencil.

Other welcome distractions include works by lesser-known Europeans, several of whom practice a romantic strain of Conceptualism. In a video performance conceived as a homage to Piet Mondrian, the Dutch-born artist Bas Jan Ader separates bouquets of flowers into orderly bunches of uniform color. Sectioned wooden bars by Andre Cadere, propped casually against the museum's walls, were once carried into the cafes, subways and galleries of 1970s Paris in a peripatetic hybrid of sculpture and performance.

Artists working some 20 years after Kelly's cut-paper experiments still had to contend with art schools that emphasized formal color training. The anti-Albers backlash finds its most concise expression in Richard Serra's Color Aid (1970-1971). In this 36-minute film, Serra (who studied with Albers at Yale) leafs through a packet of 220 colored papers with the flourish of a doctor tearing off a sheet from his prescription pad.

The final section of the show, devoted to art since 1990, feels less inspired. The neutrality of the color chart is predictably violated, first in a 1998 series of paintings by Mike Kelley that form a grid with covers of the bawdy-humor magazine Sex to Sexty, and later in two of Damien Hirst's ubiquitous spot paintings.

The most recent works acknowledge that our experience of color is increasingly mediated by corporations and consultancies, like Pantone and the Color Marketing Group. Angela Bulloch's hypnotic light box Standard Universal 256: CMY (Cyan) (2006) flashes through each color of the palette used by the Macintosh OS9 operating system.

The show's newest piece is also, in some ways, one of the oldest. Sherrie Levine's Salubra No.4 (2007) consists of 14 monochrome paintings displayed against a gray background. Levine has taken the colors from a line of painted wallpaper created in 1931 by Le Corbusier - the architect better known as an advocate of pristine white Ripolin paint.

As Batchelor writes, "Chromophobia is perhaps only chromophilia without the color."

May 26 to June 1 When the Qing Dynasty first took control over many parts of Taiwan in 1684, it roughly continued the Kingdom of Tungning’s administrative borders (see below), setting up one prefecture and three counties. The actual area of control covered today’s Chiayi, Tainan and Kaohsiung. The administrative center was in Taiwan Prefecture, in today’s Tainan. But as Han settlement expanded and due to rebellions and other international incidents, the administrative units became more complex. By the time Taiwan became a province of the Qing in 1887, there were three prefectures, eleven counties, three subprefectures and one directly-administered prefecture, with

It’s an enormous dome of colorful glass, something between the Sistine Chapel and a Marc Chagall fresco. And yet, it’s just a subway station. Formosa Boulevard is the heart of Kaohsiung’s mass transit system. In metro terms, it’s modest: the only transfer station in a network with just two lines. But it’s a landmark nonetheless: a civic space that serves as much more than a point of transit. On a hot Sunday, the corridors and vast halls are filled with a market selling everything from second-hand clothes to toys and house decorations. It’s just one of the many events the station hosts,

Among Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) villages, a certain rivalry exists between Arunothai, the largest of these villages, and Mae Salong, which is currently the most prosperous. Historically, the rivalry stems from a split in KMT military factions in the early 1960s, which divided command and opium territories after Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) cut off open support in 1961 due to international pressure (see part two, “The KMT opium lords of the Golden Triangle,” on May 20). But today this rivalry manifests as a different kind of split, with Arunothai leading a pro-China faction and Mae Salong staunchly aligned to Taiwan.

Two moves show Taichung Mayor Lu Shiow-yen (盧秀燕) is gunning for Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) party chair and the 2028 presidential election. Technically, these are not yet “officially” official, but by the rules of Taiwan politics, she is now on the dance floor. Earlier this month Lu confirmed in an interview in Japan’s Nikkei that she was considering running for KMT chair. This is not new news, but according to reports from her camp she previously was still considering the case for and against running. By choosing a respected, international news outlet, she declared it to the world. While the outside world