Of all the clubs in the world, the Club of 100 in France may be the most exclusive. Its ranks include leaders in business, politics and law, but it's the admission policy that really makes the Club des Cent, as it is known here, truly remarkable: only when an existing member dies is space made for a new one.

Officially, the club, now 96 years old, is devoted strictly to gastronomy, and when the group gathers Thursdays for lunch at legendary Paris restaurants like Maxim's, politics and business are not on the menu. Claude Bebear, the chairman of AXA, the French insurance giant, and a club member for more than two decades, says that there is "an atmosphere of real friendship; we are very close."

The same is true of the French business establishment. A close-knit brotherhood - it's nearly all male - that shares school ties, board memberships and rituals like hunting and wine-tasting, the French business elite is a surprisingly small coterie in a nation of more than 60 million people.

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

But in the wake of a US$7-billion loss attributed to a rogue trader at one of the nation's leading banks, Societe Generale, France's modern-day aristocracy finds itself in the one place it never wants to be: the spotlight.

While the trader, Jerome Kerviel, now jailed, wasn't a graduate of a top school or a member of an elite group like the Club des Cent, Societe Generale's embattled chief executive, Daniel Bouton, is both. And the fact that Bouton and other top managers of the bank have kept their posts since the scandal erupted nearly a month ago has unleashed criticism here that the French elite is an ancien regime - playing by old rules (largely its own) and quick to shift blame to protect itself.

"Is there a tendency in France for the elites to be made in the same mold and close ranks?" asks Bernard-Henri Levy, the French philosopher and social observer. "Yes, it's an old French disease."

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

In the US, Britain or Germany, Levy adds, "Daniel Bouton would not only have been relieved of his job, but he'd be in a judge's office being questioned."

Indeed, the controversy comes at a time of broader tension in both French business and politics, with a new generation fighting for power against an entrenched old guard, says Stephane Fouks, executive co-chairman of Euro RSCG, one of the largest marketing and communications firms in France.

"At the moment, French capitalism is in a crisis, and it's creating momentum for a change," Fouks says. Within the traditional establishment, he says, "everybody was friends, very diplomatic, and it was a club where at the end of the day, it was always better to find an arrangement."

PHOTOS: AFP

Members of the elite make no secret of the rules of the game. "When you are part of a small group, it is difficult to have an attitude of antagonism toward someone else in the group," says Valery Giscard d'Estaing, the former president of France. "In a bigger group, there is less interference of personal considerations."

Bouton was not available for comment. But Philippe Citerne, Societe Generale's co-chief executive and a member of its board of directors, said establishment connections have nothing to do with the fact that Bouton is staying on.

"The board of directors twice unanimously confirmed its confidence in Mr Bouton," he said. "There's no way we could deliver services to 27 million customers in 82 countries if we were a small French club."

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

At least half of France's 40 largest companies are run by graduates of just two schools, the Ecole Polytechnique, which trains the country's top engineers, and ENA, the national school of administration. That's especially remarkable given that the two schools together produce only about 600 graduates a year, compared with a graduating class of 1,700 at Harvard.

"They behave like blood relations," says Ghislaine Ottenheimer, a journalist and author who has written extensively about the French elite. "There is a sense of impunity because there is no sanction in the family."

Nevertheless, l'affaire Kerviel and especially the fate of Bouton - even President Nicolas Sarkozy has suggested that Bouton should step down - have shaken the French establishment to its core and encouraged those, like Ottenheimer, who favor change.

"The old system is dying; this is its last gasp," she says. "Bouton is part of a generation that will soon have to hand control of French capitalism to a more diverse elite."

Perhaps. But it doesn't appear that Bouton is facing an imminent slice of the guillotine - unlike American executives at Citigroup and Merrill Lynch, who were forced to step down last fall after their banks suffered huge losses from the subprime mortgage crisis.

While some analysts and business people expect Bouton to step down within a year, if not sooner, Bebear of AXA says that French chief executives have more staying power than their counterparts in the US.

"In France, the board does not fire a CEO as easily as in the US," Bebear says. "We think the CEO is responsible, but to suddenly fire the CEO is not the best way to improve things."

Bebear, who acquired broad experience in the US with AXA's purchase of well-known American companies like Equitable Life Insurance and Mutual of New York, also says that "sometimes, I feel like the CEO is a scapegoat in your country."

"The CEO of a French company is more of a monarch than in the US," Bebear says. Expanding on that theme, he compares the French chief executive to Voltaire's enlightened king, or monarque eclaire. Within France itself, Bebear, 72, is considered to be as much a kingmaker as a king.

"The press sometimes calls him the godfather of French capitalism. He is emblematic," says Philippe Favre, president of Invest in France, a government agency that encourages foreign companies to do business in France.

While Bebear built AXA in the 1980s and 1990s through bold acquisitions, the power he now wields derives from the corporate boards on which he serves and the close friendships he has made through organizations like the Club des Cent - as well as hunting parties for which he is host at his estate near Orleans. And like other members of the establishment, he finds many close associates drawn into the Societe Generale affair, one way or another.

For example, Jean-Martin Folz, the member of the Societe Generale board who is heading up the company's internal investigation of the losses, is also a board member at AXA. Bebear, meanwhile, serves on the board of BNP Paribas, which is the biggest bank in France and is rumored to be preparing a bid for Societe Generale. And the chairman of BNP Paribas, Michel Pebereau, is also an AXA board member. All three men also attended the same school, the Ecole Polytechnique.

"It is a small universe," acknowledges Jean-Rene Four tou, the chairman of Vivendi, the French entertainment giant, who is a close friend of Bebear and is an AXA board member.

Fourtou, who is also an Ecole Polytechnique graduate and a Club des Cent member, recalls that Bebear played a role in persuading him to take over as chief executive of Vivendi in 2002 after the company fell into deep financial distress after a dot-com-era acquisition spree.

"Initially, I refused to take the job," Fourtou says. But over dinner at the Four Seasons Hotel George V, Bebear and Giscard d'Estaing (another Ecole Polytechnique alum) eventually persuaded him to lead Vivendi. He quickly turned around the company, making it one of France's biggest business success stories of recent years.

"They said I had to go," he recalls of the push he received to run Vivendi. "I felt obliged."

As for the current crisis at Societe Generale, Fourtou says he doesn't think Bouton should step down right away. But he says he takes that stance not because he is an acquaintance of Bouton, or because of their intersections at the Club des Cent or any other establishment ties.

"If you change the CEO immediately, you add confusion to a problem which is localized," he says. He also says he thinks that Societe Generale's support for Bouton makes sense: "The board took the right decision, and not because of networks."

While dining and discoursing at Michelin-starred restaurants might seem the epitome of aristocratic living - at each lunch, one Club des Cent member, designated the week's "Brigadier," makes a presentation about the selection of food and wine while another critiques the meal - many members come from relatively humble backgrounds.

Fourtou, for example, was raised in the Basque region of Spain by his grandfather, who did not attend college, and he briefly ran a newspaper and book kiosk on the side to help support his wife's family after graduation from the Ecole Polytechnique.

"I grew up not rich, not poor," Fourtou says. "My father was a professor of mathematics." Similarly, Bebear's parents were teachers in the Dordogne region in southwest France.

Rather than a rigid class system, it was Fourtou's and Bebear's admission into the Ecole Polytechnique that assured their place in the elite. And that is one of the great ironies of the French establishment: while it enjoys the privileges associated with the elites of the US, entry is, if anything, much more rigorously meritocratic, based on exams and ever-narrowing selection from an early age.

Indeed, getting into Harvard, which accepted 9 percent of its applicants last year, is a breeze compared with getting into the Ecole Polytechnique.

Out of 130,000 students who focus on math and science in French high schools each year, roughly 15 percent do well enough on their exams to qualify for the two to three-year preparation course required by the elite universities. Of those who make it through that, 5,000 apply to Ecole Polytechnique, which is commonly called simply "X," and just 400 are admitted from France.

Admission is based strictly on exam grades; there isn't even an essay requirement or interview. And there are no legacy admissions, sports scholarships or other American-style shortcuts for getting into X.

"You can be the president's nephew and it won't help you get in," says Bernard Oppetit, a 1978 graduate of X who later worked for BNP Paribas before starting Centaurus Capital, a London investment fund with US$4 billion under management.

The Ecole Polytechnique was founded in 1794, during the French Revolution, to train the country's military engineers, and it officially remains under the umbrella of the French ministry of defense. Not only is the school free, but students also receive a stipend from the government to cover their expenses.

"We call it l'elitisme democratique," says Pierre Tapie, dean of Essec, a leading French business school. "These are places where you meet extraordinary people who are there because they worked hard and are among the most brilliant of a generation."

Although the school teaches high-end fare like physics, engineering, and computer sciences, its broader goal is to create a leadership cadre that shares an ordered, prioritized view of the world, says Xavier Michel, the president of the Ecole Polytechnique and an active-duty general in the French armed forces.

In France, this is known as the Cartesian system, after the mathematician and philosopher Rene Descartes, and Michel says the school encourages its students "to modelize" the world. And when they eventually become chief executives, he says, "they understand what are the capabilities of their companies. They understand what they can do and what they can't do."

Until, of course, models run off the rails - as they so often do in the business and financial worlds, regardless of what country devises them.

The Taipei Times last week reported that the rising share of seniors in the population is reshaping the nation’s housing markets. According to data from the Ministry of the Interior, about 850,000 residences were occupied by elderly people in the first quarter, including 655,000 that housed only one resident. H&B Realty chief researcher Jessica Hsu (徐佳馨), quoted in the article, said that there is rising demand for elderly-friendly housing, including units with elevators, barrier-free layouts and proximity to healthcare services. Hsu and others cited in the article highlighted the changing family residential dynamics, as children no longer live with parents,

It is jarring how differently Taiwan’s politics is portrayed in the international press compared to the local Chinese-language press. Viewed from abroad, Taiwan is seen as a geopolitical hotspot, or “The Most Dangerous Place on Earth,” as the Economist once blazoned across their cover. Meanwhile, tasked with facing down those existential threats, Taiwan’s leaders are dying their hair pink. These include former president Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文), Vice President Hsiao Bi-khim (蕭美琴) and Kaohsiung Mayor Chen Chi-mai (陳其邁), among others. They are demonstrating what big fans they are of South Korean K-pop sensations Blackpink ahead of their concerts this weekend in Kaohsiung.

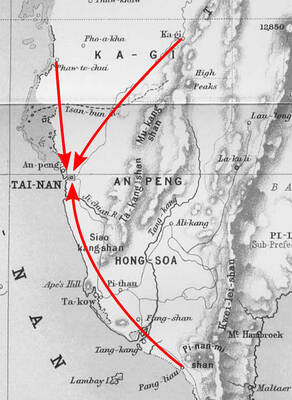

Oct 20 to Oct 26 After a day of fighting, the Japanese Army’s Second Division was resting when a curious delegation of two Scotsmen and 19 Taiwanese approached their camp. It was Oct. 20, 1895, and the troops had reached Taiye Village (太爺庄) in today’s Hunei District (湖內), Kaohsiung, just 10km away from their final target of Tainan. Led by Presbyterian missionaries Thomas Barclay and Duncan Ferguson, the group informed the Japanese that resistance leader Liu Yung-fu (劉永福) had fled to China the previous night, leaving his Black Flag Army fighters behind and the city in chaos. On behalf of the

I was 10 when I read an article in the local paper about the Air Guitar World Championships, which take place every year in my home town of Oulu, Finland. My parents had helped out at the very first contest back in 1996 — my mum gave out fliers, my dad sorted the music. Since then, national championships have been held all across the world, with the winners assembling in Oulu every summer. At the time, I asked my parents if I could compete. At first they were hesitant; the event was in a bar, and there would be a lot