Javier Bardem opens the door to his New York hotel suite dressed head to toe in Prada, a short beard framing his craggy features and a courteous welcome in his sleepy, hooded eyes. His room has spectacular views over Central Park. There is a pair of Peeping Tom binoculars on a side table; Bardem is quick to say they're not his - they come with the room.

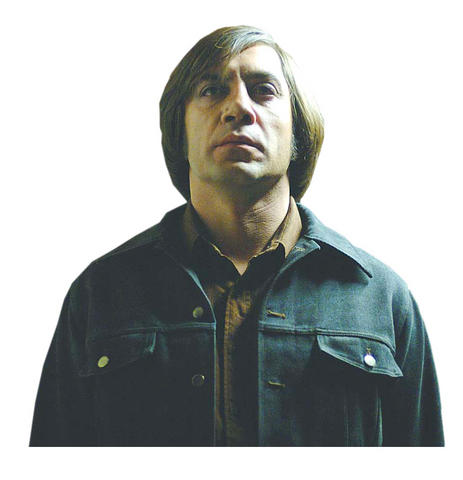

It's fitting that Bardem should be scaling such symbolic heights. In 2001 he was Oscar-nominated for best actor for his portrayal of the gay Cuban writer Reinaldo Arenas in Before Night Falls - the Julian Schnabel film for which the Spanish actor first learned English. He was the quadriplegic lead, stubbornly fighting for his right to die, in The Sea Inside, which won an Oscar for best foreign film four years later. And what with winning the award for best supporting actor at the BAFTAs Sunday night for his role as Anton Chigurh, the psychopathic killer in the Coen brothers' No Country for Old Men, things seem to have shifted into a different gear. With his helmet-haired angel of death, Bardem is considered to have created one of the great cinematic villains.

The movie is also his first big American film and, having been a huge star in Spain for well over a decade, Bardem finds himself on the brink of a full-blown Hollywood career. Though an indisputably great actor, he is something of an unlikely Tinseltown star: barrel-chested; a broken nose; and a thick Castilian accent. Yet People magazine recently rated him one of the sexiest men alive, and the world's finest directors all seem to want to hire him. "It's sort of a great and beautiful accident that has happened to me," he says, flicking the ash from a cigarette into a glass of water.

PHOTO: AP

His turn in Mike Newell's adaptation of Gabriel Garcia Marquez's novel Love in the Time of Cholera is on general release next month in the US, and Bardem has just finished Woody Allen's Vicky Cristina Barcelona, appearing alongside Penelope Cruz, his old friend and rumored new lover. He's also slated to star in Nine, Rob Marshall's musical adaptation of Fellini's 8 1/2, and in Francis Ford Coppola's Tetro.

In an interview, Coppola singled him out as an heir to, and even an improvement on, Al Pacino, Jack Nicholson and Robert de Niro. After their early successes, these legends became rich and complacent, the director said. But Bardem is ambitious and hungry, unwilling to rest on his laurels and always "excited to do something good."

"It was amazing to hear him comparing me to those major artists," says Bardem. "For you to have an idea [of how amazing], I've always said, 'I don't believe in God, I believe in Al Pacino.'" When Pacino saw Before Night Falls, Bardem chuckles, Schnabel gave him Bardem's number. Pacino phoned him in Madrid, even though it was the middle of the night there, and left a message on his answer phone saying that he wanted to tell him straight away how much he'd loved the movie. "I keep that tape with me," says Bardem. "It's one of the most beautiful gifts I've ever received. I don't care whether it's a lie or not, whether he was just being nice or not. I have it."

Bardem, now 38, grew up in a theatrical family. His grandparents were actors, and his mother, cousins and two siblings are all in the profession. His uncle, Juan Antonio Bardem, was a director imprisoned by Franco for his anti-fascist films.

"I come from a very political background," says Javier Bardem, who as a child hung around theaters and film sets. At six, he appeared in Fernando Fernan Gomez's The Scoundrel. "A guy with a gun came up to me and pretended to shoot me, and I was supposed to laugh but I began to cry instead. The director said, 'It's not what I wanted but I like it.' And that day I realized that I will always fight with directors." But Bardem had another thing to fight against first: the inevitability of his career path. His mother, who raised him alone, was often unemployed for long periods: "I saw it from the inside, I knew how difficult it was." He chose to become a painter, working to pay his way through art school. He still likes to draw, and often sketches faces to help him understand a character better. (In Allen's new film he plays a painter: "He fights with the blank canvas, and finally he makes love with it.") But Bardem soon discovered that art wasn't his true calling. "One day I did a small role with a few lines and," he says, taking a short, sharp breath, "I enjoyed it. I thought, 'Fuck, man, I have it inside of me, whatever it is I have it inside of me."' Jamon, Jamon (1992), in which Bardem plays a crotch-stroking ham salesman-turned-underwear model with a penchant for bull-fighting in the nude, made him and his co-star Cruz famous. But he refused to be typecast as the brute, the libidinous lover, and chose to work frugally, picking only the most interesting parts.

In Hollywood, Bardem faced a similar struggle at first: being stereotyped as the drug dealer or Latin lover. "It's even boring to read the scripts," he says, "so one can't imagine what it would be like to play the characters. The Coen brothers' thing was kind of a miracle. It's really difficult for their movies to have room for a foreign actor, because their movies are really deeply American." Bardem dreams that one day he might be able to imagine all the characters he's played in the same room, and that they would all be so different that they wouldn't have anything to say to each other. "I picture Before Night Falls, the poet, talking to Chigurh," he says, with a laugh. "I don't know what they would talk about. Or, The Sea Inside, the guy laid down on the sofa, maybe he'd ask Chigurh to kill him." Many of the characters Bardem chooses seem constrained, either physically or by political circumstance, and he brings rich, understated shades to their contradictions. His character in The Sea Inside says he can only cry by smiling, and Bardem manages to convey geniality and tragedy in one expression. But Chigurh seems entirely without contradictions - he just keeps on coming.

"Perhaps not contradictions," Bardem says, "but he has an internal struggle: 'the world is corrupted, the world needs some kind of punishment, and I'm here to remind them that.' He doesn't have any pleasure in what he does; he almost has pain in doing it.

"There was a challenge, which is how to bring the symbolic side of violence into human behavior, so that people see a human being and not a terminator machine, otherwise we don't feel for him, we just think, 'Oh, here comes the machine.' But at the same time, he has to have this unstoppable machine attitude." Bardem describes Chigurh as "a guy who comes from nowhere and goes out to nowhere," and admits he felt quite alienated filming on location in Texas. "Being a foreigner, in a foreign movie, my first American movie, in a foreign landscape, working one or two days a week, with a lot of free time - and that haircut - there was a moment when I felt totally isolated, totally detached, and that's what I brought to the character. Somehow I understood him, without trying to understand him." People were sometimes a little scared, Bardem continues, when he went to the local shop and forgot to wear a cap. Josh Brolin, who plays Chigurh's prey, told New York magazine about the effect of the hair when the actors went to a bar during the shoot - "Bardem looked around and sighed: 'Man, I'm not going to get laid for three months.'" When I ask Bardem if this turned out to be true, he guffaws then says: "I'm not going to say - it's a good legend." He refuses to talk about his relationship with Cruz. Coincidentally, his mother, Pilar, played her mother in Pedro Almodovar's Live Flesh, in which Bardem also appeared. In one of the film's memorable scenes, she helps Cruz's character give birth on a bus, severing the umbilical cord with her teeth.

Bardem insists he isn't seduced by Los Angeles. "I don't drive," he says. "Sometimes people around you see what is happening to you as something extraordinary, but not yourself.

"The fact of being a Spaniard, and living in Spain, enables me to see things from the outside, with a camera B. It's good to go back to your roots and to see everything with a second camera. When you see yourself from the outside, you see how small everything is, how unimportant."

May 11 to May 18 The original Taichung Railway Station was long thought to have been completely razed. Opening on May 15, 1905, the one-story wooden structure soon outgrew its purpose and was replaced in 1917 by a grandiose, Western-style station. During construction on the third-generation station in 2017, workers discovered the service pit for the original station’s locomotive depot. A year later, a small wooden building on site was determined by historians to be the first stationmaster’s office, built around 1908. With these findings, the Taichung Railway Station Cultural Park now boasts that it has

Wooden houses wedged between concrete, crumbling brick facades with roofs gaping to the sky, and tiled art deco buildings down narrow alleyways: Taichung Central District’s (中區) aging architecture reveals both the allure and reality of the old downtown. From Indigenous settlement to capital under Qing Dynasty rule through to Japanese colonization, Taichung’s Central District holds a long and layered history. The bygone beauty of its streets once earned it the nickname “Little Kyoto.” Since the late eighties, however, the shifting of economic and government centers westward signaled a gradual decline in the area’s evolving fortunes. With the regeneration of the once

The latest Formosa poll released at the end of last month shows confidence in President William Lai (賴清德) plunged 8.1 percent, while satisfaction with the Lai administration fared worse with a drop of 8.5 percent. Those lacking confidence in Lai jumped by 6 percent and dissatisfaction in his administration spiked up 6.7 percent. Confidence in Lai is still strong at 48.6 percent, compared to 43 percent lacking confidence — but this is his worst result overall since he took office. For the first time, dissatisfaction with his administration surpassed satisfaction, 47.3 to 47.1 percent. Though statistically a tie, for most

In February of this year the Taipei Times reported on the visit of Lienchiang County Commissioner Wang Chung-ming (王忠銘) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and a delegation to a lantern festival in Fuzhou’s Mawei District in Fujian Province. “Today, Mawei and Matsu jointly marked the lantern festival,” Wang was quoted as saying, adding that both sides “being of one people,” is a cause for joy. Wang was passing around a common claim of officials of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the PRC’s allies and supporters in Taiwan — KMT and the Taiwan People’s Party — and elsewhere: Taiwan and