There was a time when American Leather, an upscale furniture manufacturer based in Dallas, Texas, had a few easy-to-describe product lines. Its "traditional" couches and chairs appealed to the mature consumer with an established home, according to Jennifer Green, a spokeswoman for the company, while its "contemporary" furnishings spoke to a younger and trendier buyer. For everyone else, there were the pieces in somewhat generic, enduring styles, "like what you'd see at Crate & Barrel," she said.

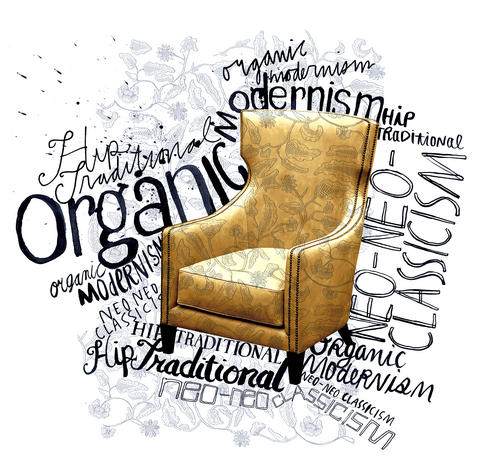

But that was back in 2006, before the company began producing a new breed of furniture, one that was harder to characterize. How do you label a serpentine sectional with a tufted back, scrolled arms and tapered wooden legs, that looks traditional when upholstered in chestnut leather, but sleek and contemporary in white ultrasuede? Or an armless corner chair with slightly flared backs, buttonless tufts and an attached flat cushion?

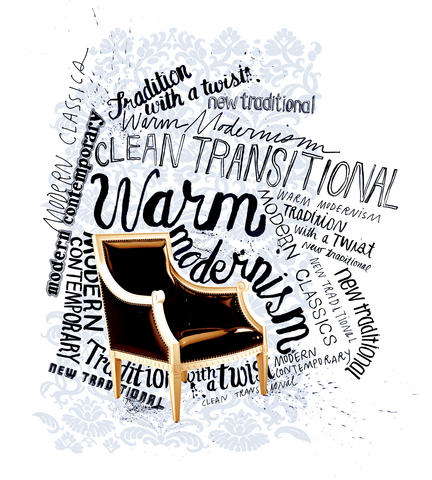

Late last year, after months of deliberation and a series of intense strategy sessions, the company finally came up with three new categories, none of them models of clarity, which it splashed across 6m-high banners in the entryway of its showroom in High Point, North Carolina: "Boutique Traditional," "Clean Transitional," and - perhaps the most inspired - "Modern Contemporary."

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

American Leather is one of many manufacturers and retailers now contending with the problem of naming or describing furniture that is designed to defy categorization. In recent years, as decorators and indie furniture designers rebelled against the minimalism that held sway early in the decade, an individualistic, mix-and-match aesthetic has become fashionable, and is now becoming the norm. This look - contemporary spaces peppered with antiques and crafty pieces, bespoke furnishings that tweak traditional forms with unusual materials - has filtered into the mainstream consciousness, thanks largely to TV makeover programs, magazines and blogs. Now companies aimed at the mass-market consumer are having to figure out how to package it.

For designers like Thomas O'Brien and Jonathan Adler, who helped pioneer the "new eclecticism," as it has sometimes been called, defining their approaches was relatively simple. O'Brien used the phrase "warm modernism" to set his work apart from what he saw as the coldness of minimalist modern interiors, and Adler spoke of "tradition with a twist" - a term that, along with "warm modern," has since been appropriated by legions of salesclerks stumped for a way to explain why old-fashioned wood furniture might be coated in black lacquer or upholstered in wasabi green. (Elaborating recently on his "vision for design," Adler said, "I see no reason not to offer classic pieces for foundation but always done with mod moxie.")

But how to stand out from the pack when rebellion has become the rule? Names and slogans are now "the hardest part of my job," said Edward Tashjian, the vice president for marketing at Century Furniture in Hickory, North Carolina, who oversees the naming of individual pieces and entire collections. "Literally, every time I do it I want to quit and find a new career." Coming up with a name for one of the new collections "that's descriptive and engaging - not to mention hasn't already been used, isn't completely banal and meets the approval of the rest of the management team - is a nearly impossible task," he said.

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

Describing a collection in a way that is compelling, evocative and clear can mean the difference - at least to those charged with doing it - between attracting an entirely new group of customers and repelling existing ones. Consumers these days "define themselves in different terms than the ones we use in the furniture industry," like traditional or contemporary, said Bruce Birnbach, the president of American Leather. "If we speak to them in our industry terms we're going to miss. You have to be very careful about putting the customer into a box."

Sometimes the high stakes can lead to a certain timidity. The marketing team at Century spent more than three months conducting focus groups, researching consumer data and combing thesauruses before introducing a collection that became available to consumers earlier this year, under the rather tame rubric "New Traditional."

"The words 'classic' and 'traditional' are emotionally charged words and mean different things for different people," Tashjian explained of the struggle. "Twenty to 30 percent of our customers say they want traditional furniture but they don't want their grandma's or their parent's look. They want it to be fresher and contemporized so that it's their own. They want it to have some kind of classic feel, but they want it to be slightly different."

Bernhardt Furniture Co, which in the past has focused on traditional furniture but has lately expanded its repertory, also took several months coming up with the name for a new collection that merges old and new, although its approach was somewhat more adventurous. "We were looking for lifestyle-type names that just kind of sounded young and fresh and updated," said Heather Eidenmiller, Bernhardt's director of brand development. "You've got to find a name that pulls them in but that would never turn them off," she added: "A name that can be pronounced, and that doesn't sound like influenza." (For a brief moment in 2006, the company considered naming its neo-traditional Wilshire Blvd line for the Pantages Theater in Hollywood, but "you could just hear people say 'Pantages is contagious,'" Eidenmiller said.)

For Tashjian of Century, today's mix of old and new is part of an ongoing tale. "This is what that whole neo-classic movement was all about," he said, "back around the time of Napoleon and that whole consulate era, when they wanted to go back to the Greeks and Romans and Ionic columns but they wanted to make it their own. One of the greatest paradoxes of this human condition we live in is people have these conflicting desires: first, to belong to a group, and second, to be unique. And these two things fight with each other and that happens with furnishings, too."

A few lucky souls like Adler find that the conflicting desires pose no marketing challenge at all. Recently he introduced several pieces from his Regent Collection (more are to arrive this year) that include baroque 18th century-style occasional tables that have been stripped of some ornamentation, lacquered white and given polished nickel feet. His name for this style? "I call it 'Neo-Neo-Classicism.' I could keep neo-ing but I think neo-neo- is a good expression of it."

May 26 to June 1 When the Qing Dynasty first took control over many parts of Taiwan in 1684, it roughly continued the Kingdom of Tungning’s administrative borders (see below), setting up one prefecture and three counties. The actual area of control covered today’s Chiayi, Tainan and Kaohsiung. The administrative center was in Taiwan Prefecture, in today’s Tainan. But as Han settlement expanded and due to rebellions and other international incidents, the administrative units became more complex. By the time Taiwan became a province of the Qing in 1887, there were three prefectures, eleven counties, three subprefectures and one directly-administered prefecture, with

President William Lai (賴清德) yesterday delivered an address marking the first anniversary of his presidency. In the speech, Lai affirmed Taiwan’s global role in technology, trade and security. He announced economic and national security initiatives, and emphasized democratic values and cross-party cooperation. The following is the full text of his speech: Yesterday, outside of Beida Elementary School in New Taipei City’s Sanxia District (三峽), there was a major traffic accident that, sadly, claimed several lives and resulted in multiple injuries. The Executive Yuan immediately formed a task force, and last night I personally visited the victims in hospital. Central government agencies and the

Among Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) villages, a certain rivalry exists between Arunothai, the largest of these villages, and Mae Salong, which is currently the most prosperous. Historically, the rivalry stems from a split in KMT military factions in the early 1960s, which divided command and opium territories after Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) cut off open support in 1961 due to international pressure (see part two, “The KMT opium lords of the Golden Triangle,” on May 20). But today this rivalry manifests as a different kind of split, with Arunothai leading a pro-China faction and Mae Salong staunchly aligned to Taiwan.

As with most of northern Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) settlements, the village of Arunothai was only given a Thai name once the Thai government began in the 1970s to assert control over the border region and initiate a decades-long process of political integration. The village’s original name, bestowed by its Yunnanese founders when they first settled the valley in the late 1960s, was a Chinese name, Dagudi (大谷地), which literally translates as “a place for threshing rice.” At that time, these village founders did not know how permanent their settlement would be. Most of Arunothai’s first generation were soldiers