Greatness hovers just outside American Gangster, knocking, angling to be let in. Based in rough outline on the flashy rise and fall of a powerful 1970s New York drug lord, Frank Lucas, the film has been built for importance, with a brand-name director, Ridley Scott, and two major stars, Denzel Washington as Lucas, and Russell Crowe as Richie Roberts, the New Jersey cop who brings him down. It’s a seductive package, crammed with all the on-screen and off-screen talent that big-studio money can buy, and filled with old soul and remixed funk that evoke the city back in the day, when heroin turned poor streets white and sometimes red.

This being an American story, as its title announces and Steven Zaillian’s screenplay occasionally trumpets, there’s plenty of blue in the mix too, worn by some of New York’s very un-finest. Lucas was among the city’s most notorious underworld hustlers, but one of the film’s points (at times you could call it a message) is that he was just doing what everyone with ambition, flair and old-fashioned American entrepreneurial spirit was doing, including cops: getting a piece of the action. His piece just happened to be bigger than most, stretching across Harlem and snaking into other neighborhoods, into alleys and apartments where someone with ready cash and a hungry vein was always aching to get high.

You see a few of those veins, popping, all but jumping in anticipation of another hit. Sometimes the needle slides into a clean arm, though every so often the camera comes uncomfortably close as a spike jabs into a suppurating wound. You could call these images metaphoric, something about the oozing, bleeding body of the exploited underclass, but mostly they’re just graphic evidence of the damage done. Despite the intermittent nod to someone nodding out and even dying, this isn’t about the suffering of addicts or of those forced to watch their neighborhoods perish alongside them. It’s about good guys and bad, a classic story of white hats and black squaring off at the corral at 116th Street and Eighth Avenue.

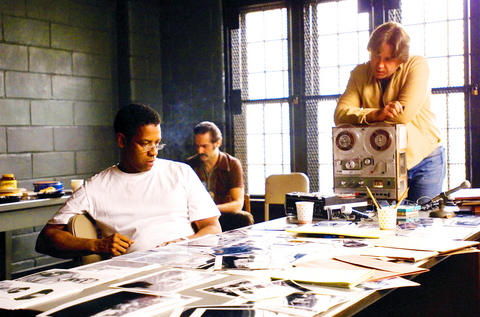

PHOTO: AP

Crowe, his jaw thrust forward as aggressively as his pelvis, wears the white hat, while the silky, smooth-moving, smooth-talking Washington wears the black. They’re irresistible, though neither possesses the movie because each occupies a separate if parallel story line. Washington has the more developed and dynamic role, which he inhabits easily, whether flashing his wolfish grin or draining the affect from Lucas’ face to show the soulless operator beneath the swagger and suit. Lucas’ rival, Nicky Barnes (Cuba Gooding Jr. in a sharp, small turn), wore the pimp threads and fedoras the size of manhole covers (he also read Machiavelli). Lucas dressed like the businessman he believed himself to be and was.

Formally, the plot takes the shape of a simple braid, with Lucas’ and Roberts’ stories serving as individual narrative strands that become more and more tightly plaited. Complicating this simple, at times overly mechanical back-and-forth design is a third player with a smaller strand, a corrupt New York detective, Trupo (Josh Brolin in a knockout performance), who shakes down Lucas and other larcenous types. The baddest bad man in town, a thug’s thug, Trupo wears his power as confidently as the long black leather coat he whips on for battle. He hassles Lucas, who hates him in turn, and openly indulges his contempt for Roberts because the other cop is honest, which means he’s a threat to Trupo and his kind.

It’s hard not to fall for these men pumping like pistons across the screen, which is as much part of the movie’s allure as its problem. Scott doesn’t escape the contradiction that bedevils almost every Hollywood movie about gangsters, which cry shame, shame, as they parade their stars, crank the soul and showcase the foxy ladies, the swank digs and rides. Washington obviously enjoys sinking into villainy, but he never finds the lower depths. There’s little of the frightening menace the actor brought to Training Day, where you see the pleasure his character derives from his sadism. Even when Lucas goes ballistic, beating a man to pulp, the film tosses in a laugh about the proper way to clean a bloodied rug.

Seriousness has always been one of Scott’s strengths as a director, but when his material has skewed too light, too frivolous, the gravity and purpose etched into each one of his meticulous, beautiful images have also helped sink films. He couldn’t make an ironic gesture if he wanted to, or toss off an idea or a shot. Everything counts, even if it shouldn’t. Scott makes the case for his and his new film’s seriousness in its opener, which shows Lucas tossing a match at a man who has been doused with gasoline and then pumping bullets into the burning, screaming figure.

This is the match that ignites the story of a criminal overlord who, without mercy or remorse, takes down one human being after another, many of whom, like the addicts he supplied, were as helpless as that burning man. By rights this match should also ignite a tragedy, and you can almost feel Scott trying to coax the material away from its generic trappings toward something rarefied, something like Francis Ford Coppola’s 1972 definitive American story, The Godfather. He comes closest to that goal with the suggestion that the lethal pursuit of the American dream is not restricted to one or two families — the Corleones, say, or the Sopranos — but located in a network of warring tribes that help to obscure the larger war of all against all.

The America in this film isn’t a melting or even a boiling pot; it’s a bitter object lesson about the logic of market-driven radical individualism.

June 2 to June 8 Taiwan’s woodcutters believe that if they see even one speck of red in their cooked rice, no matter how small, an accident is going to happen. Peng Chin-tian (彭錦田) swears that this has proven to be true at every stop during his decades-long career in the logging industry. Along with mining, timber harvesting was once considered the most dangerous profession in Taiwan. Not only were mishaps common during all stages of processing, it was difficult to transport the injured to get medical treatment. Many died during the arduous journey. Peng recounts some of his accidents in

“Why does Taiwan identity decline?”a group of researchers lead by University of Nevada political scientist Austin Wang (王宏恩) asked in a recent paper. After all, it is not difficult to explain the rise in Taiwanese identity after the early 1990s. But no model predicted its decline during the 2016-2018 period, they say. After testing various alternative explanations, Wang et al argue that the fall-off in Taiwanese identity during that period is related to voter hedging based on the performance of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Since the DPP is perceived as the guardian of Taiwan identity, when it performs well,

A short walk beneath the dense Amazon canopy, the forest abruptly opens up. Fallen logs are rotting, the trees grow sparser and the temperature rises in places sunlight hits the ground. This is what 24 years of severe drought looks like in the world’s largest rainforest. But this patch of degraded forest, about the size of a soccer field, is a scientific experiment. Launched in 2000 by Brazilian and British scientists, Esecaflor — short for “Forest Drought Study Project” in Portuguese — set out to simulate a future in which the changing climate could deplete the Amazon of rainfall. It is

Artifacts found at archeological sites in France and Spain along the Bay of Biscay shoreline show that humans have been crafting tools from whale bones since more than 20,000 years ago, illustrating anew the resourcefulness of prehistoric people. The tools, primarily hunting implements such as projectile points, were fashioned from the bones of at least five species of large whales, the researchers said. Bones from sperm whales were the most abundant, followed by fin whales, gray whales, right or bowhead whales — two species indistinguishable with the analytical method used in the study — and blue whales. With seafaring capabilities by humans