The generation of actors who emerged from Laurence Olivier's Old Vic theater in London, and those who trained at the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC) and the National, are what Ian McKellen calls "the family that is British theater." You can probably hear him saying it - those rich, round tones that could advertise Englishness and that, when he's dressed as a king or a wizard, strike the audience with something like a moral force. Working in this family, he says, "is not like doing a movie with a film star who is protective of their own territory and you're having to accommodate that. If you're in a play with Frances de la Tour or Maggie Smith or Vanessa Redgrave, there are certain shared assumptions." One of these is the primacy of the play - "The play's the thing!"

Another is a certain generational solidarity; an understanding that, for years, the private lives of a great many of their number were criminalized and, after being decriminalized, were so curtailed by disapproval as scarcely to register the change. "My friends are my family," McKellen says, and it is no small pronouncement.

When it was announced earlier this year that McKellen would appear as King Lear in Trevor Nunn's RSC production, theater-land gasped and fell to the floor. At last! The grandest of the actor knights in the grandest of Shakespeare's plays! In New York, where the play opened in September after its Stratford, England, run, you couldn't get a ticket for love nor money, and the foyer of the Brooklyn Academy of Music on the night I attend is a hilarious swim of famous faces and well-to-do New Yorkers trying casually to ignore them. When Lauren Bacall crosses the floor with Lynn and Vanessa Redgrave, the provocation proves too great: the elbow of every person present instantly connects with the rib of their neighbor.

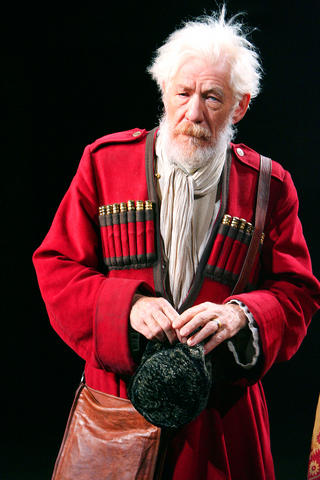

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

"Yes, she did enjoy it," McKellen says three days later when I mention Bacall. We are in his friend's loft in Chinatown, where he's staying for the New York run. His hair, dyed white for the role, stands up like a fire in a waste-paper basket and his eyes are that undiluted blue that, no matter how kind he's being, always looks vaguely accusing.

"When we said good night, she looked me in the eyes and said oh, how she loved acting! That it was a wonderful thing to do."

Playing Lear has put him in an expansive mood on the subject of human nature, although one suspects he doesn't need much encouragement. He is fondly regarded as the grandest of the grand British actors, grander than Anthony Sher, grander than Derek Jacobi, grander, even, than Ben Kingsley, and one imagines him waiting by the window if the postman is late, lamenting, "I am a man more sinned against than sinning." It's a bit unfair since, unlike Kingsley, he can send himself up, calling himself "Serena" as a camp play on "Sir Ian" and appearing recently in an episode of Extras in which he pondered, "How do I act so well? What I do is I pretend to be the person I'm portraying in the film or play."

PHOTO: AP

But an impression of grandness prevails. It derives partly from McKellen's accent, elocutioned out of its northern English origins into that mythical RSC English, partly from the formality of his speech - he gives each thought lengthy gestation before articulating it - and mostly from the sheer volume of classical roles he has played. You hardly need see him as Lear: you can imagine it in your mind's eye.

Still, he plays the role well, flipping between capriciousness and mania and a touching self-hatred when he curses his daughters to barrenness. Things get a bit shouty on the heath in Act II - what Germaine Greer called the RSC's habit of "mouthing, gnashing, yelling, snarling, munching, spitting, gritting, grinding, shrieking, slobbering, snapping and gobbling" the lines, instead of just saying them. It's a tendency of which McKellen is aware. "On the whole actors shout when they don't know what they're doing, trying to make an impact. So I think the journey on this production for me has been learning how to talk rather than to declaim and shout. But there's a lot of rhetoric in the play. He talks to the elements, for goodness sake."

When Sean Mathias, theater director and his former partner, with whom he lived for many years, heard McKellen was doing Lear, he rolled his eyes and said, "I hope you're not going to put on one of those funny voices." McKellen looks wounded. "And I said to him, what do you mean? I don't put on funny voices!" There is a long, sardonic pause. "And then, of course, you realize that you do."

He wears plimsolls, baggy trousers and a loose flowing shirt, a sort of dashing Robinson Crusoe effect that makes me ask if he is single. "Yes," he says drily. "Can you throw anyone my way?"

McKellen is 68. When he was 18 he won a scholarship from his school in Bolton in the north of England to study English at Cambridge. Scholarship boys were in the minority and he was mocked for his accent, which he hastily set about changing, though the northern inflection is still, occasionally, detectable in the shallows. McKellen hopes that the days of having to disguise oneself to be successful have passed.

The household he grew up in was liberal, even "radical" for the time, in that his parents were pacificists, "northern nonconformists" who "judged a person on how they related to society as a whole. You didn't admire people because they were rich or had status, but on how they treated other people." His father was a civil engineer, his mother a housewife with mild aspirations to be an actor. She died of breast cancer when McKellen was 12 and he has scant memories of her. "She loved listening to the radio. She had her favorites and she used to - I do remember her telling me the story of plays she'd heard on the radio and we went out as a family to see plays and she did a little bit of acting of an amateur sort. But not much when she was married. They just liked the theater."

After her death his father quickly remarried, he suspects out of concern for his teenage son as much as anything else. He got on well with his stepmother, Gladys - well in the sense that she was kind to him. The problem for McKellen was that the blind spot in his family's liberalism was sexuality.

When he looks back on those years, what he's struck by is the silence; the strained, polite relationship that arranged itself around the elephant in the room and has affected his behavior in relationships ever since. "It wasn't a topic that was ever discussed. At school, church, home, in the newspapers, on the radio. Absolute silence. My parents and I were a victim of that. I didn't meet anyone I identified as gay - though that wasn't the word we used then. Queer was the word, I suppose - until I went to Cambridge. And even then it was not a subject ever talked about. Ever. Not in my circles. So I was a very, very late developer. I was 28 before it was legal for me to make love. It's a dreadful, dreadful thing." He pauses. "You can never get over that. I can't."

The Cambridge he went to in the late 1950s was in transition from an ancient establishment into something more modern; the men in the year above him were back from national service, shortly to be abolished, and chafed against the curfews and petty rules. Despite that, and the snobbery, McKellen felt free there. He says if he hadn't gone to Cambridge, he probably wouldn't have become an actor. He started acting in college drama societies and was singled out for praise by the student and national press during his first year. There was tough competition in his year - he was part of a generation at the university that included Corin Redgrave, Peter Cook and Derek Jacobi, with whom he was quite in love and only discovered years later had been in love with him, too. How infuriating. Well, he says, that's how it was. "There was nowhere you could go where people were relaxed and openly gay. But then I did find one place, and that was the theater."

After university he joined Laurence Olivier's Old Vic, which was "a wonderful place to be - Maggie Smith and Joan Plowright and Lynn Redgrave and Billie Whitelaw and Robert Stephens and Michael York and Ronald Pickup and Derek Jacobi and Anthony Hopkins and Mike Gambon, all there together. At the Old Vic."

You can see the problem: McKellen, full of youthful confidence, stuck it out for a bit, then left to join a smaller company where he had a hope in hell of landing a leading role sometime before retirement. Olivier was amazed that anyone would leave his orbit voluntarily and sent him a terrifically pompous letter. "I've still got it. He said that he was 'haunted by the specter of lost opportunity.'" McKellen smiles. "He thought he had a way with words."

Over the next 20 years, he played almost every Shakespearean hero and villain there is: Hamlet, Iago, Richards II and III, Coriolanus, Macbeth, Romeo. He's not a fan of the Globe, which he finds too large and bothered by air traffic noise, and he doesn't think it would have looked like that, anyway, in Shakespeare's day; for example, when King Lear says, "Pray you, undo this button. Thank you, sir," McKellen thinks it's apparent the line was "written for an audience who could actually see the button."

One of the best things about the current production is Frances Barber as Goneril, but McKellen is too discreet to name his favorite leading lady. "Well, I have friendships to guard. The one I've worked with most is Judi Dench." I've heard she swears like a trooper. "That's not the first thing that occurs to me about Judi Dench. She's a Quaker. That's partly why she's so nice. Quakers are terrific. I had a wonderful relationship with Francesca Annis when we did Romeo and Juliet. And Irene Worth, who played Volumnia when I did Coriolanus at the National, a great thrill - she likes doing what I do. We jazzed."

Mmmm; the jazz approach was apparently less appreciated by Helen Mirren, with whom McKellen appeared in a production of Strindberg's Dance of Death in 2001. "We work a little bit differently. She's a wonderfully technical actress and once settled on what she wants to do, that on the whole is what she does. I prefer rooting around, still discovering; I think she found that unhelpful for her. I hope we're good friends. There weren't any great bust-ups."

McKellen's acting changed, subtly, in 1988 when, at the age of 49, he publicly came out. Within his own circle he had never disguised his sexuality, but the burden of hiding it from the public had weighed on him and cramped his spirit in ways he found difficult to measure, until it was lifted. "Once you come out, all the problems go away, because the problem becomes somebody else's. It's not yours any more." He was instrumental in the founding of Stonewall, the gay rights charity. "I was emotionally freed up, not only in life but in work. Acting became easier because I was unedited."

I wonder, given how late in life this came about, that he didn't at some stage try to fudge it by going out with women. "I did go out with a girl once. I didn't much enjoy it. No." He looks thoughtful. "I see other people who enjoy traveling, not just in the sense of going around the world but enjoying exploring relationships with people. And I've never been like that. Years of being inhibited, put down, labeled, defined." He pauses. "I think I've only ever been daring in one area of my life - in my work."

He says: "If I could rewrite my life it would be that, a) my mother didn't die when I was 12, because if so she might even be alive now. And that b) I got round to telling my father, who died when I was 24 [about being gay]. Because if a child can't tell his parents something as central to his nature as that, there becomes a division. It's ironic that the right wing complains about gay people being somehow alien to family life and wanting to destroy it. Well, no. It's the laws of the land that inhibit gay people that destroy families. So. There we are. Had my father lived, my fantasy is I'd have become closer to him by being honest. But who knows."

Does he wish he'd had kids? "No, I never did. I used to think I'd had a lucky escape and that I'd have been a dreadful parent, and most parents are, of course. It never crossed my mind - it wouldn't have been allowed. These days the ease with which gay people consider having a family is wonderful. And they make very good parents because they think about it very seriously. No gay person has a child by chance because of a one-night stand. They have to go through the most convoluted bureaucracy. And in my experience their kids are wonderful because they've had so much proper love and attention. So I missed out on being a parent with some relief. I think there's one baby in my family, and that's me."

McKellen's late-breaking film career came as a surprise, and a joy, because he was never particularly ambitious for stardom. In his 20s he'd look at the young Albert Finney's film career and wonder if he was underachieving. But on the whole, he decided, the theater was where he belonged. "I don't think it would have been good for me to have been discovered by films at the age Albert Finney was, or Tom Courtenay, or Alan Bates. I wasn't ready for it."

In 1995, he successfully portrayed Richard III onscreen as a snarling, 1930s fascist, but before that McKellen's biggest movie role to date had probably been as Death, in Last Action Hero. (Hollywood producers called on him, as they seemed to on all classical English actors back then, only when they needed a cadaverous villain of some sort.) After Richard III he was seen as a potential lead, and in 1998 won an Oscar nomination for his role as James Whale in Gods and Monsters, a superbly delicate and tortured performance. "It isn't quite like sharing a stage with somebody," he says of acclimatizing to the new medium. "You're acting not so much with the other actor, but with the camera. That's a very personal relationship that film stars have. The equivalent in the theater would be an actor who has a very personal relationship with the audience that excludes the other actors. Well," he says caustically, "you try not to do that."

When the offer came in to play Gandalf in Peter Jackson's Lord of the Rings, lots of fine subhead:

Ian McKellen has enthralled audiences on the big screen, small screen and stage. Now, he

becomes King Lear in a play that has sold out all over the world

British actors had already turned it down, including, reportedly, Anthony Hopkins and Sean Connery. How they must be cursing themselves now. The success of the films has made McKellen not only richer, but celebrated to a degree that gives him freedom to do more of what he wants. The role must have been a walkover - Gandalf speaks with a Shakespearean intonation but without the difficult sentence structure. I wonder if he has discussed how to play a wizard with his friend Michael Gambon, who does Dumbledore over in the Harry Potter franchise. "Funnily enough, we never have." He grins.

As a relief from the hard labor of Lear, three times a week the company performs Chekhov's shorter tragedy, The Seagull, in which McKellen plays the elderly and mercifully sedentary role of Sorin. When it played in New Zealand, Helen Clark, the prime minister, said drily to McKellen afterwards, "That's a cheery little number." He liked her for that. Has he met Gordon Brown yet? "I have. I met him at the civil partnership ceremony between Michael Cashman, who's a member of the European Parliament, and Paul Cottingham, his partner. It was quite an occasion. There was a letter of love and regard sent from Tony Blair, still prime minister, and Gordon Brown, the prime-minister-in-waiting, was present. I just thought, well ..." His voice drops; weary, proud. "Yessssss!"

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) hatched a bold plan to charge forward and seize the initiative when he held a protest in front of the Taipei City Prosecutors’ Office. Though risky, because illegal, its success would help tackle at least six problems facing both himself and the KMT. What he did not see coming was Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (將萬安) tripping him up out of the gate. In spite of Chu being the most consequential and successful KMT chairman since the early 2010s — arguably saving the party from financial ruin and restoring its electoral viability —

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,