Jamie Bell is at an awkward age. "It seems like the boyish era is coming to an end," he says, with the weird distance of one who has been reading about himself in newspapers since childhood. He is 21 and no longer suitable for what he calls the "kid-becoming-a-man kind of role." But he is still, just, recognizable as the disheveled boy who played Billy Elliot. "When you did a movie a while ago about dancing, which everyone associates you with and still remembers and has fond memories of, there's always going to be that point where you have to do something where people are like, 'Oh ... ."

Bell would like it if people hurried up and had their "Oh" moment. And Hallam Foe may just be the film to bring it on. "It deals with sex and stuff like that," he says. "And some pretty heavy emotional turmoil as well." It is Bell's ninth film, adapted from the novel by Peter Jinks and co-starring Sophia Myles as a woman with whom the 17-year-old Hallam becomes obsessed after the death of his mother. He follows her through the streets of Edinburgh, climbs on to her roof to spy through her bedroom window and negotiates a tricky line between childish infatuation and adult creepiness. The film's darkness - Hallam believes his father's new wife murdered his mother - is alleviated by Bell's natural screen charm and some fine black humor.

Some months before our interview, I watch him filming Hallam Foe on location in Edinburgh. Professional autograph-hunters sulk in wait on the pavement and Bell approaches them, frowning silently to sign their photos. He is compact and earnest-looking, and between takes paces up and down the pavement, muttering. "Are you worried about the timings?" says David Mackenzie, the director. "Nope," says Bell. His frown deepens; he beats time against his legs.

PHOTO: EPA

Later, Mackenzie tells me, "There's no one Jamie's age in this country to touch him. You'd have to draw comparisons with the heroes of 1960s cinema. He's bloody good. Very laid back to work with. Takes notes."

"He's very smart," says Gillian Berrie, the producer. "He's got a wise old head on young shoulders. He's considerate. He's not been tainted by Hollywood, which you imagine someone his age might have been. He does his homework every night. He's got a long career ahead of him."

Bell was 13 when he made Billy Elliot. He wasn't a stage brat, but neither was he new to performing - he'd won a load of regional tap-dancing prizes and wanted to be either a dancer or a rock musician. Drama school was too remote from his life in the north-east of England to countenance, and it wasn't until he won the role of Billy Elliot that he realized how desperately he wanted to do it, to act. And very seriously he takes it, too, although that seriousness is undercut by a convincing modesty.

"I still have no idea what I'm doing," he says. "I'd feel very self-conscious in an acting class. They'd probably tell me I was doing it all wrong." He has, he says, been "riding the wave of luck," and his roles don't form any obvious pattern: a character part in the Peter Jackson blockbuster King Kong, the lead in David Gordon Green's gothic indie film Undertow, Smike in Nicholas Nickleby. His accent has roamed about from rural Georgian to suburban Californian to, in Hallam Foe, mild Scottish. Bell takes the view that you should treat acting like any other kind of business. "It's about showing your range. You do something like King Kong, and it's a different way of acting and working, and it looks good on your [resume]."

Balancing "passion projects" with commercial ones is something he has learned from studying the career of his hero, Paul Greengrass. "Paul obviously mixed in [the dramatization of] Bloody Sunday with things like The Bourne Supremacy. When I watched Bloody Sunday, I blubbed all the way through. He does the human condition very well."

Hallam Foe is a passion project, and Bell said yes to it partly because he admired another of Mackenzie's films, the noir-ish Young Adam. "I hadn't seen Ewan McGregor be that good in a while. But when he returns to his roots ... ."

This might strike McGregor as a bit cheeky, but roots are important to Bell, who grew up in Billingham, northern England, and has moments - particularly when he was in the Philippines on the set of Flags of Our Fathers, the Clint Eastwood-directed account of the battle of Iwo Jima - when the distance he has traveled from his upbringing makes him wince. "My heart was pounding every single day. You know, to be a boy from Billingham working with Clint Eastwood." He calls Mackenzie part of "a dying breed of British directors who stay close to their roots".

Does he live in London now? He flicks me a suspicious look. "Yeah. Just outside."

When I see him next, Bell has just flown into London from the US, where he's filming, to present an award at the British Academy awards. He is much more relaxed, the frown has gone and he is capering about in grungy jeans and indie-band hair. His appreciation for the human condition makes him sound more pretentious than he is - he tells me he has a "crazy schedule," and looks instantly mortified. "I said to my best friend I didn't have time to see him and he was just, like, 'You're a bastard. I hate you.'"

Bell

continued from p14

If he is wary of talking about his living arrangements it's because of some negative coverage about his friendship with Stephen Daldry, the director of Billy Elliot. After the film came out, they spent a lot of time together - Bell was characterized as a kind of Eliza Doolittle to Daldry's Henry Higgins, a Geordie guttersnipe adopted by a southern toff and remodeled in his image. Bell's accent is all over the place, but that's because, as he says, he has "been living out of a suitcase since I was 15. Unfortunately." He still sees Daldry all the time and their relationship has changed, over the years." As I become more adult, he becomes more childish, and I become the father and he becomes the son." Yikes, that sounds a bit Method. How much advice does Daldry give him? "He's never said no, you can't do that [job]. But he would ask, do you like it? Do you want to do this? On all fronts."

I wonder if Bell felt pushed out when his mentor got married and had a child. "No, I love his wife; Lucy's great. He's one of those people in your life who you know will always be there. Our families are really integrated, and our friends. It's a big group, really."

Bell has an elder sister, and his mother brought them up when his father left home. Bell has no memory of him. He idolizes his mother, who, he says, "is probably the strongest, most independent person I know. She raised me and my sister by herself. Single parent - the government doesn't really help. That was incredibly difficult. And then two kids wanting to go to dance school, so she'd take us to competitions around the country. It's a really big deal for parents to be able to support their kids' hobbies."

It has been to his father's credit that, since Bell became famous, he hasn't come forward to claim 50 percent credit for his genetic make-up. "I wish he had - that would've been hilarious." Bell says this with deep, adolescent sarcasm. "But no. He didn't. And he still hasn't. Good luck to him. It makes no real difference, coz he was never there. Never having it, you don't miss it."

You're expected to miss it.

"That's bollocks."

Like a lot of young film actors, Bell has had to learn how to spend time on his own. He keeps a journal and likes to read, mainly biographies and, rather sweetly, "instruction manuals." At the time of our interview, he is reading a biography of Kurt Cobain. "I don't take any photographs. I travel a lot by myself, and I feel weird taking photos on my own. If there's a bunch of us taking pictures of each other, that's fine. But on my own ... I find that writing in my journal is enough. It's not about the place I'm in - Tokyo or wherever - it's about the mindset that I'm in."

The success of Billy Elliot - Bell won a British Academy award for it - could have turned him into a brat in the mould of the young Leonardo DiCaprio (in fact, he's a big fan of DiCaprio's and thinks he has been unfairly cast as a "pretty boy"). And, indeed, Bell does knock about in a kind of British rat pack with, among others, Max Minghella, actor son of director Anthony, but he has an easy humor that seems to deflate the hype around him. And he is too funny-looking - strong-featured, but a little wonky - to inspire much hysterical female attention. Bell really would rather be Albert Finney than Tom Cruise.

Among his contemporaries, he admires James McAvoy, but says that, generally, "I don't think there's a lot of actors out there right now who really know what they're doing at all. There was a generation of actors who were classically trained, knew what it was. But now I think younger actors, there's no real progression. They're just doing it."

There was a moment of deja vu at the British Academy awards when he passed Abigail Breslin, the 10-year-old star of Little Miss Sunshine, who was nominated for a best supporting actress award. "She said a quick hello and it was weird, because that was me about four or five years ago."

Bell has developed a kind of tour-guide patter to cover his feelings about his first role. He talks about "huge mental processes" and "concepts." The film, he says, "is part of my heritage." If Billy Elliot hadn't succeeded, "I would've gone back to school and still be living up north. So I'm incredibly grateful. When people ask me about it, they say, 'Oh, you probably don't want to talk about it.' But without that, I wouldn't have got anything else. You can't deny what got you here."

He identifies with Daniel Radcliffe, who was making headlines that week in the London play, Equus. There was the same icky expectation of seeing a former child actor in a sex scene, but Radcliffe pulled it off, as does Bell in Hallam Foe. It's important to him that the film isn't characterized too much as his getting-his-kit-off debut. His friend, Anne Hathaway, with whom he worked on Nicholas Nickleby, had a similar problem after her success in the Princess Diaries. "She was in this film Havoc - it's not very good and there's a weird vibe about it, which is that she's taking her clothes off. It's obviously the producer or her manager or her publicist or someone from Disney saying, 'She's getting her tits out, it never happened, she was never in Princess Diaries.'"

You don't get this sense in Hallam Foe, partly because the character is so strong and partly because Bell is so compelling in it, able to move between light and dark without showing the joins. And he is a likable actor, which is why, although Hallam has lots of unappetizing habits such as voyeurism and stalking, he is still, essentially, sympathetic.

When it comes to his career, Bell doesn't like to be interfered with. He is wary whom he takes advice from and suspicious of the advice others are taking. Of Radcliffe in Equus, he says, "There is always that element of 'Who's getting him to do this?'"

Working on Peter Jackson's King Kong was like being on the "biggest independent movie I'd ever done - because you're in New Zealand and miles away from the studios." The drawback to working with someone like Eastwood, meanwhile, is that he doesn't have much time for small fry such as Bell. "It's kind of hard working with people like Peter Jackson and Clint Eastwood, because you don't really get to know them. They're very warm, but there's not that collaborative energy you get from smaller films."

Given the choice, he says, "I'll always opt for drowning in a loch in Hallam Foe. It's much more interesting." He has to think about these things, to plot his course, because he is no longer a novelty act. As Bell becomes an adult performer, he can't just be good for his age; he has to be good, full-stop, because, "It's getting a little more serious now."

Has the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) changed under the leadership of Huang Kuo-chang (黃國昌)? In tone and messaging, it obviously has, but this is largely driven by events over the past year. How much is surface noise, and how much is substance? How differently party founder Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) would have handled these events is impossible to determine because the biggest event was Ko’s own arrest on multiple corruption charges and being jailed incommunicado. To understand the similarities and differences that may be evolving in the Huang era, we must first understand Ko’s TPP. ELECTORAL STRATEGY The party’s strategy under Ko was

Before the recall election drowned out other news, CNN last month became the latest in a long line of media organs to report on abuses of migrant workers in Taiwan’s fishing fleet. After a brief flare of interest, the news media moved on. The migrant worker issues, however, did not. CNN’s stinging title, “Taiwan is held up as a bastion of liberal values. But migrant workers report abuse, injury and death in its fishing industry,” was widely quoted, including by the Fisheries Agency in its response. It obviously hurt. The Fisheries Agency was not slow to convey a classic government

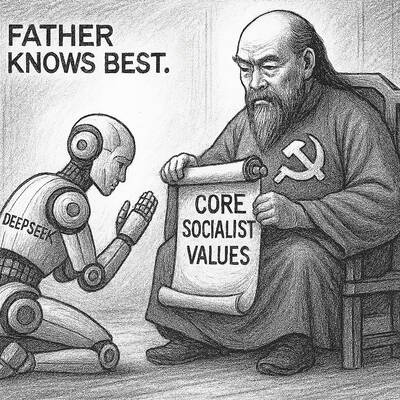

It’s Aug. 8, Father’s Day in Taiwan. I asked a Chinese chatbot a simple question: “How is Father’s Day celebrated in Taiwan and China?” The answer was as ideological as it was unexpected. The AI said Taiwan is “a region” (地區) and “a province of China” (中國的省份). It then adopted the collective pronoun “we” to praise the holiday in the voice of the “Chinese government,” saying Father’s Day aligns with “core socialist values” of the “Chinese nation.” The chatbot was DeepSeek, the fastest growing app ever to reach 100 million users (in seven days!) and one of the world’s most advanced and

It turns out many Americans aren’t great at identifying which personal decisions contribute most to climate change. A study recently published by the National Academy of Sciences found that when asked to rank actions, such as swapping a car that uses gasoline for an electric one, carpooling or reducing food waste, participants weren’t very accurate when assessing how much those actions contributed to climate change, which is caused mostly by the release of greenhouse gases that happen when fuels like gasoline, oil and coal are burned. “People over-assign impact to actually pretty low-impact actions such as recycling, and underestimate the actual carbon