Lucas Cranach liked underarms. Twice he painted a woman reaching up to a branch with her left arm, exposing the flesh under her shoulder. Why that hollow fascinated him is a secret long lost, but it is the sort of detail that makes this German Renaissance artist's depictions of the female nude revolutionary. Cranach was not the first artist to paint women naked, but he may be the first to have made it obvious he wanted to go to bed with them. With his taste for stagey sadomasochism - he painted Judith and Salome as snake-eyed slayers of men - and his penchant for tight-laced garments, he was the Helmut Newton of the 16th century.

There's something decadent and ignoble about Cranach. His paintings make me gawp. I can't get over the eroticism of his Cupid Complaining to Venus. Beside the skinny goddess of love, for all the world like a model in a 21st-century fashion magazine, is her son Cupid, who's being attacked by bees. It comes with a verse that explains this (in case you hadn't guessed) as an image of desire's inevitable punishment: "While the boy Cupid plunders honey from the hive, the bee fastens on his finger with a piercing sting ... the brief and fleeting pleasure which we seek is hurtful, mingled as it is with wretched pain."

Yet - and this is what keeps me coming back - the painting is a lot more ambivalent than a literal reading of the emblem might suggest. Cranach's Venus is so insistently sexual, with her wide hat and chunky necklace setting off those little breasts, that narrow waist, those long thighs. She has something about her of an emaciated sinner in a medieval depiction of hell, and yet the feeling the painting creates, outrageously, is that hell has its delights. Sex is dirty, and that's why we enjoy it, says Cranach.

PHOTO: AP

Well, he had this on excellent theological authority: his best friend was Martin Luther, leader of the Reformation, who believed that no one could be saved by good works or charity, because humankind was irredeemably corrupted by the fall of Adam and Eve. Our sinful nature is too dark and evil for our own efforts to win God's forgiveness; it comes instead as gratuitous grace, and only for a few. Cranach was godfather to Luther's first child.

Why isn't Cranach a more revered and famous figure? Well, Cranach is difficult, even if you realize the greatness of German Renaissance art, because of his sheer productiveness. Paintings by him fill galleries all over Europe. He was a court artist in what by then was already an old-fashioned way, churning out hunting scenes and portraits with the help of an efficient workshop. Where his rival Albrecht Durer mythologized himself as a Christ-like redeemer of humanity and dramatized the anguish of creativity in his print Melencolia I, Cranach's personality vanishes in professionalism.

This is why the new exhibition at London's Courtauld Gallery - which takes a sharp look at Cranach's obsession with sex and death in a selection of nudes painted around 1526, at the height of the Reformation - is a brilliant idea. It makes the real man emerge from the sheer scale of his output.

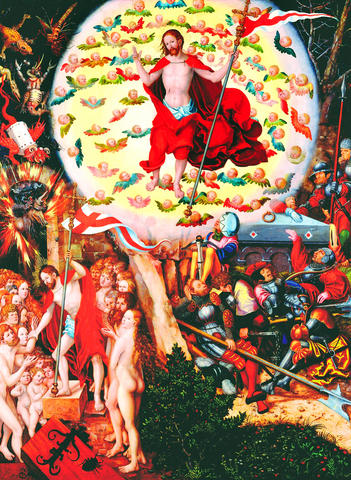

PHOTO: AP

Durer almost steals it, however, with his engraving Adam and Eve, which somehow gives mere printed paper the weight of marble. Dated, on the tablet hanging from a tree in Paradise, to 1504, this is the grandest German attempt to absorb the Italian Renaissance; the nude figures of Adam and Eve are modeled on classical Greek statues with even, restrained physiques, balanced limbs and poses. Here Durer expresses the cult of the proportionate nude to icy perfection.

But what you see, moving from Durer in 1504 to Cranach in 1526, is how German artists warped this classical ideal by fusing it with a heritage that went back into the middle ages and even to primitive, pre-Christian times, to produce a bizarre, twisted version of Renaissance art. You feel the savage wilderness outside the walled towns in Cranach's pictures, the wild Wald beyond. Some of his most stunning works are hunting scenes, and this show includes a tremendous print of a theme he takes to lunatic lengths in paintings of mass hunts in which men and women of the court fire bows and arrows at stags and boars.

Beautiful drawings of these animals, featured in this exhibition, show how intimate Cranach became with the world of the hunt, giving rough magic to his mythological scenes. A faun and his family live in a very Germanic tangle of fir forest. Diana sits on a stag like the ones his masters hunted. This insistence on rooting myth in reality makes Adam and Eve, and the myth of the Fall, Cranach's perfect subject.

Cranach painted his Adam and Eve in 1526, not just in the year he became godfather to Luther's child, but also in the aftermath of the Reformation's most violent crisis, the German Peasant War, a popular rising sparked by Luther's writings. Luther called for the peasants to be massacred, which they were. It was a moment to reflect darkly on the sinful and depraved nature of human beings. But what makes us so wicked? Our desire. A Protestant painter might therefore take more liberty than a Catholic one to portray the bodies and poses he finds arousing - and that's what Cranach does. His Eve is tempting him, as he paints her. That's why the dirtiness of desire clings to his art, after 500 years. He makes the Renaissance feel bad and wrong.

Behind a car repair business on a nondescript Thai street are the cherished pets of a rising TikTok animal influencer: two lions and a 200-kilogram lion-tiger hybrid called “Big George.” Lion ownership is legal in Thailand, and Tharnuwarht Plengkemratch is an enthusiastic advocate, posting updates on his feline companions to nearly three million followers. “They’re playful and affectionate, just like dogs or cats,” he said from inside their cage complex at his home in the northern city of Chiang Mai. Thailand’s captive lion population has exploded in recent years, with nearly 500 registered in zoos, breeding farms, petting cafes and homes. Experts warn the

The unexpected collapse of the recall campaigns is being viewed through many lenses, most of them skewed and self-absorbed. The international media unsurprisingly focuses on what they perceive as the message that Taiwanese voters were sending in the failure of the mass recall, especially to China, the US and to friendly Western nations. This made some sense prior to early last month. One of the main arguments used by recall campaigners for recalling Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers was that they were too pro-China, and by extension not to be trusted with defending the nation. Also by extension, that argument could be

Aug. 4 to Aug. 10 When Coca-Cola finally pushed its way into Taiwan’s market in 1968, it allegedly vowed to wipe out its major domestic rival Hey Song within five years. But Hey Song, which began as a manual operation in a family cow shed in 1925, had proven its resilience, surviving numerous setbacks — including the loss of autonomy and nearly all its assets due to the Japanese colonial government’s wartime economic policy. By the 1960s, Hey Song had risen to the top of Taiwan’s beverage industry. This success was driven not only by president Chang Wen-chi’s

Last week, on the heels of the recall election that turned out so badly for Taiwan, came the news that US President Donald Trump had blocked the transit of President William Lai (賴清德) through the US on his way to Latin America. A few days later the international media reported that in June a scheduled visit by Minister of National Defense Wellington Koo (顧立雄) for high level meetings was canceled by the US after China’s President Xi Jinping (習近平) asked Trump to curb US engagement with Taiwan during a June phone call. The cancellation of Lai’s transit was a gaudy