Marilyn Manson sits in semi-darkness and profound air-conditioned chilliness, in a suite in London's otherwise bright and temperate Metropolitan Hotel. He has made his room as tomb-like as he can, for two reasons: 1) It allows Manson to wear head-to-toe leather, even though it's an unseasonably warm week in April (outside, the streets of London are filled with breezy, Cornetto-eating young things who swish around in slips of summer dresses, flashing limbs coated in Johnson's Holiday Skin); and 2) It builds on Manson's undead, crypt-frequenting myth.

He is talking about his new album, which he's in the UK to promote. It's called Eat Me, Drink Me, and it has recurring motifs: death, the devil, mutilation and vampires, mainly. "I've always thought that association, with the romanticism of vampires, was a bit too obvious a fit for me," he's saying. His voice is low, halting and purposely monotonous. It's got so much bass in it that it actually makes your ribcage reverberate. Manson's a wordy, circuitous talker; his sentences are rammed with gothy rhetoric, he's very oblique. He's trying to tell me something, but I'm not quite sure what.

"But a vampire is only something that can be killed by stabbing it through the heart," he says. "And that... I guess, that's my weakness."

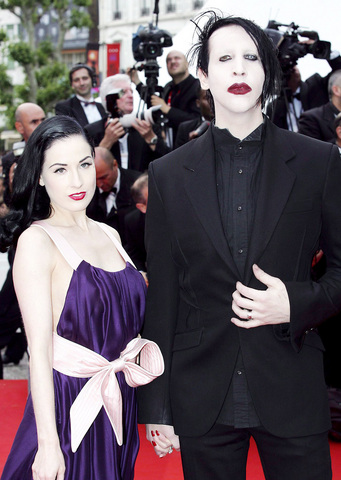

PHOTO: EPA

Being stabbed through the heart is your weakness?

"Metaphorically."

Do you mean, er, that love can destroy you?

"Yes. No. But also a vampire is a character that's only at night- time, and ultimately... er, preys on young women. And drinks blood. This idea of consuming someone, whether it's literal or a metaphor, is quite romantic..." Right.

"You know?"

Not... really.

Marilyn Manson is not scary. He should be. He wears all the trappings of scariness; scariness is his currency. There's his look — he's a long, thin, crone-like streak of goth, with overdyed black hair, geisha-white foundation and blood-red lipstick; he wears contact lenses that turn his eyes a milky, sinister shade of nothing. His interior-design ethic is similarly informed: he famously filled his Hollywood mansion with knick-knacks of supreme ghoulishness — a jacket made from the skin of conjoined lambs, Nazi uniforms, the foetus of an unborn child (which Manson christened Ludwig Von Manson, because he thinks 'it's a lovely name').

There's his art, his act — his wailing, theatrical paeans to death and obscenity, which are called things like Smells Like Children and Angel With the Scabbed Wings and (UK bonus track and my own particular fave) Baboon Rape Party. His videos, which are crammed with (simulated, I think) dark sex acts, suicide and bleeding; and his stage shows, one of which featured the routine leashing and debasement of a particularly slavish fan. There's his assumed name — a merging of Marilyn Monroe and Charles Manson — with its overtones of death and victim and blackest, bleakest celebrity. (He's actually called Brian Warner. Only his mother calls him that now.)

And most of all, there's his reputation. Marilyn Manson's spent the past decade or so routinely (effortlessly, even) shocking the socks off conservative, Christian, right-wing America. In the US he's been vilified as a Satan-worshipping, animal-sacrificing, bisexual corrupter of the youth; he's been banned from performing in several states. He's the US's self-styled "god of fuck." It all reached a nadir in 1999, when he was blamed for inspiring the Columbine shootings (this is pertinent — we meet 48 hours after news of the campus shooting at Virginia Tech breaks). Manson plays out differently in the UK, where the campness of goths inspires amused affection in the non-goth faction of the public.

But no, I'm not scared of Marilyn Manson. Maybe it's because he's 38 years old and it's hard to be truly dangerous when you're middle aged. Or maybe it's because, in the flesh, he doesn't exude any kind of menace. One on one, Manson's calm and self-contained, and sort of benign.

He's had a tough year. Even in the grand scheme of his darkness, things grew very dark indeed for Manson through 2006. Eat Me, Drink Me might seem like just another 11-song romp through teenage angsts and obsessions. It features songs called Just a Car Crash Away and also Mutilation is the Sincerest Form of Flattery and... oh, you get the idea. But Manson says it's more than that.

It isn't hard to guess what triggered Manson's descent into despair. In December last year, Manson's wife, the burlesque performer Dita Von Teese, filed for divorce. Their marriage had lasted about a year (they got hitched in December 2005, at midnight in a gothic mansion in Tipperary); it followed a four-year relationship. A lot of people were surprised and dismayed by the news. The couple had had good celebrity symmetry. Dita and Marilyn were the Posh and Becks of alternative popular culture. Their alabaster skins and black hair and mutual fondness for bright lipsticks; the suggestion of a flagrant and decadent sex life.

Von Teese has blamed Manson for the demise of their marriage — she cites his alleged infidelities, his "demons" and the influence of "Mommie Dearest," Manson's troubled mother. Manson, meanwhile, blames his depression on the marriage.

Like all celebrities, Marilyn Manson is something of a cliche. His psychology is transparent. Brian Warner was a geeky, unfortunate, awkward child, and so he was marginalized by other children. He was sickly, he was lonely. His parents sent him to a strict and religious school, where he developed a major antipathy toward religious dogma — a theme that recurs in his music. He had a difficult relationship with his mother — who, he's realized recently, "is not just crazy, as I thought she was as a youngster, but is actually mentally ill in a way that's been a big burden on my mind; and also in a way that is hereditary ..." — who he tried to strangle when he suspected her of being unfaithful to his father. His grandfather, whom he described in 2000 in his autobiography, The Long Hard Road Out of Hell, as "the ugliest, darkest, foulest, most depraved figure of my childhood," lived with them; Warner discovered that he secretly wore women's underwear, and that he used to masturbate in the family basement while surrounded by toy trains. Brian Warner, perhaps inevitably, became a self-harming, self-absorbed teenager.

He was born physically unexceptional, so he made himself look exceptional with make-up. He believed himself to be insignificant, so he became a rock star and ensured that millions of people would love him or at least take notice of him. "I think one of the reasons I got on stage was because I have a hard time relating to people," he has said in the past. "It was a matter of being invisible as a kid. I didn't have to create an alter-ego, I had to create an ego." Following some fits and starts and changes to the line-up in the band (he once set fire to his drummer), he secured a record deal. In 1996, he scored his breakthrough moment with his album Antichrist Superstar. In 1998, Mechanical Animals sold multiple millions and Manson was officially big time.

Fame, infamy, breakdowns, overdoses, high drama, a broken relationship from yet another raven-haired, red-lipped beauty (actress Rose McGowan) followed; as did the bother over Columbine.

On which: has anyone blamed him for the Virginia Tech shootings yet?

"Not as far as I know. But I wouldn't be surprised if I was blamed. You know, it all seems very manufactured to me."

In what way?

"In the way that there's candlelight vigils, but I haven't seen anyone crying. Not one single person crying. Someone said to me yesterday: I'm sure you're full of mixed emotions. And I'm not, really. I don't really care. I don't know anyone involved in it. If you lose emotion, and you gain it back, you realize that hate and love are very important to distribute properly. So I'm not going to waste any kind of emotion on things that aren't related to me. It doesn't mean that you have to be insensitive or cold, or have no sort of empathy. It just means that when you do have an emotion, make it extreme."

Sometimes, Marilyn Manson seems like a man in make-up, with a major midlife crisis. A man — furthermore — who doesn't recognize his midlife crisis as such, because he considers himself creatively superior and thus immune to middle age. It would be easy to dismiss him. He talks a lot of nonsense, and his conversation — like his lyrics — sometimes overflows with the kind of rhetoric and flawed sentiment that doesn't stand up to close inspection. Yet he's funny. He's not beyond laughing at himself.

He has occasional moments of something approaching self-awareness. Even his pretensions — which are manifold and enormous in scale — are somewhat innocent and authentic. Whimsical teenage pretensions, basically.

Plus he's got really great skin — you've got to admire that. What's his secret? "Make your body a place where germs are afraid to live." We share make-up tips. "I like Shiseido and Nars," he says. He doesn't take his make-up off before bed. Ugh, I say. He laughs. 'I have to shave, because I am a man — whatever you may think; but that's about the only thing I do that disturbs my make-up." I tell him I like his lipstick. He says he'll find out the color. "It's not my usual. For years I was wearing a very specific wine color. But this one is my more masculine lipstick, I think. Ha ha!"

Is he happy?

He pauses. It is a loaded question for a goth of his stature. An awful lot of fans depend on him not being happy.

"For the most part, yeah. More so than I was a year ago. And definitely more than I was 10 years ago. I feel, like, being in a position where I simply have no reason to apologize for just being myself, and where I don't have to make what I do an apology for me, or a defense of who I am."

June 23 to June 29 After capturing the walled city of Hsinchu on June 22, 1895, the Japanese hoped to quickly push south and seize control of Taiwan’s entire west coast — but their advance was stalled for more than a month. Not only did local Hakka fighters continue to cause them headaches, resistance forces even attempted to retake the city three times. “We had planned to occupy Anping (Tainan) and Takao (Kaohsiung) as soon as possible, but ever since we took Hsinchu, nearby bandits proclaiming to be ‘righteous people’ (義民) have been destroying train tracks and electrical cables, and gathering in villages

Swooping low over the banks of a Nile River tributary, an aid flight run by retired American military officers released a stream of food-stuffed sacks over a town emptied by fighting in South Sudan, a country wracked by conflict. Last week’s air drop was the latest in a controversial development — private contracting firms led by former US intelligence officers and military veterans delivering aid to some of the world’s deadliest conflict zones, in operations organized with governments that are combatants in the conflicts. The moves are roiling the global aid community, which warns of a more militarized, politicized and profit-seeking trend

The wide-screen spectacle of Formula One gets a gleaming, rip-roaring workout in Joseph Kosinski’s F1, a fine-tuned machine of a movie that, in its most riveting racing scenes, approaches a kind of high-speed splendor. Kosinski, who last endeavored to put moviegoers in the seat of a fighter jet in Top Gun: Maverick, has moved to the open cockpits of Formula One with much the same affection, if not outright need, for speed. A lot of the same team is back. Jerry Bruckheimer produces. Ehren Kruger, a co-writer on Maverick, takes sole credit here. Hans Zimmer, a co-composer previously, supplies the thumping

Dr. Y. Tony Yang, Associate Dean of Health Policy and Population Science at George Washington University, argued last week in a piece for the Taipei Times about former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) leading a student delegation to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) that, “The real question is not whether Ma’s visit helps or hurts Taiwan — it is why Taiwan lacks a sophisticated, multi-track approach to one of the most complex geopolitical relationships in the world” (“Ma’s Visit, DPP’s Blind Spot,” June 18, page 8). Yang contends that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has a blind spot: “By treating any