From the late 1930s through the 1950s, the words "Peer's Daughter" were regularly lodged in British tabloid headlines above the startling doings of one or another of the Mitford sisters, daughters of the less startling, but equally eccentric, Lord and Lady Redesdale.

The papers announced that Unity Mitford, a close and doting member of Hitler's intimate circle, had shot herself upon the outbreak of the war, and was being repatriated. (Two years later she died of a brain injury.) They recorded the imprisonment of the beautiful pro-Nazi Diana, along with her saturnine husband, Oswald Mosley, leader of Britain's Fascists.

They registered a drastic swing of the Mitford political compass when Jessica, 17 and an impassioned leftist, eloped to Spain with Esmond Romilly, Winston Churchill's nephew, to join the republican side in the Civil War. Anthony Eden, the foreign secretary, had a destroyer take them right back. The bit about "not who you are, but who you know" was meaningless in their particular England. Who you were was who you knew.

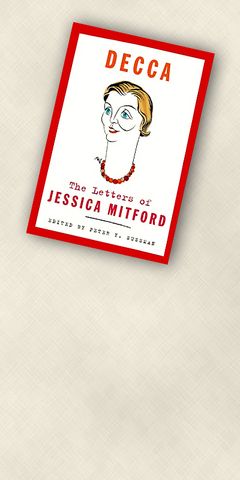

Such public Mitford extremes were not really separate from the private ones, attached to an upbringing for which odd would be the blandest understatement. Both are amply reflected in Decca: The Letters of Jessica Mitford. If the first could hold grim consequences (with an undertone of comic absurdity), the second, for all their absurd comedy, held an undertone of chill.

Nancy Mitford, seemingly more conventional, recorded her family's extravagances in a series of engaging, nonfictional fictions. (Jessica's memoir, Hons and Rebels, was a kind of fictional nonfiction.) Nancy put a name on it all: "The private Mitford cosmic joke."

It was as if the childhood nursery, whimsically feral, with its private language and unsupervised, faintly Lord of the Flies air — the parents' eccentric interventions were the odd comets traversing a child-run solar system — had stayed with them as they grew up.

They went out into the world, unchastened and retaining a little of the private language and a good deal more of the private thinking. L.P. Hartley wrote, "The past is another country; they do things differently there." The Mitfords towed that other country and all of its differences along behind them.

Even the quieter ones did some towing. Deborah has been recalled declaring as a child that she intended to become a duchess, and she did, by a circuitous if not (we presume) magical route. She married the Duke of Devonshire's younger son; he became heir when his older brother died in the war, then duke himself.

It was Jessica, known as Decca, who traveled farthest and freest. She and her family severed the towline. (Years later, Lord Redesdale wrote in his will "except Jessica" for each bequest to his children.) It would be a temporary severing, though the part-frayed ends still chafed.

Decca migrated with Esmond to the US, where they lived a happy mix of mild bohemianism and social butterflying. Among their close friends was Katharine Graham, who would inherit the Washington Post. When Esmond returned to Britain as a fighter pilot and was killed, Decca worked for a fashionable dress shop, and later for the wartime Office of Price Control.

Moving to San Francisco with her daughter, Constancia, she married a radical lawyer, Robert Treuhaft, joined the Communist Party and began decades of civil rights activism. This continued even after she left the party in 1958, because she found it had gone not wrong, but stodgy. After writing the hugely successful Hons and Rebel and The American Way of Death, a witty and devastating look at the funeral industry, she found herself a celebrity and, to her astonishment, wealthy.

All this, and a great deal more, is contained in Decca, a 744-page collection of letters, painstakingly and usefully edited by Peter Y. Sussman, a journalist and friend who has contributed lengthy biographical accounts between sections.

The letters are a treasure. Decca lived and battled by a pen that was as graceful and witty as it was sharp. Teeth were her means of propulsion, her wings; and the marks they left were singularly fine and even to be prized. She was, consummately, a happy warrior; in her letters, as in her books, she gets at her targets — the funeral directors, fat-farmers, prison establishment, writing programs — with their own words. There is no insult like a mirror's.

Only a few letters battle directly; most report the details to friends. Her activism, though, is only one subject in a collection that deals with virtually every part of her life: her husbands, her children, her writing, her publishers and, more and more as the years pass, the Mitfords.

Each one gets her own treatment. Early on, there was a touching reconciliation with her mother, and as the years pass, this becomes warmer and more solid, though after Lady Redesdale's death, Decca can't resist noting to a friend one of her mother's diary entries: "Heifer born today. Mabel (a servant) two weeks holiday. Decca married. Tea with Fuehrer." (The Redesdales were visiting Unity in Germany.)

If Decca has forgiven her mother her one-time Hitler sympathies, has nothing but tenderness for the deluded and disabled Unity, is cautiously affectionate with Nancy and warm though prickly with Deborah, she is unbending about Diana's steely and unrepentant Fascist history. Visiting London with her son, Benjamin Treuhaft, who is half Jewish, she notes Diana's offer of a meeting: "I thought better not, as I didn't want Benj turned into a lampshade."

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the